New Year’s Eve 2019: Ian Lipkin, a famed Columbia University epidemiologist, is having dinner with his wife and a fellow scientist. He gets a confidential phone call from a highly placed source in China: There’s a cluster of pneumonia-like illnesses in the city of Wuhan caused by a novel coronavirus. The source says it’s not that big a deal: It doesn’t look very transmissible.

“I was told not to worry about it,” Lipkin recalls.

It was something to worry about.

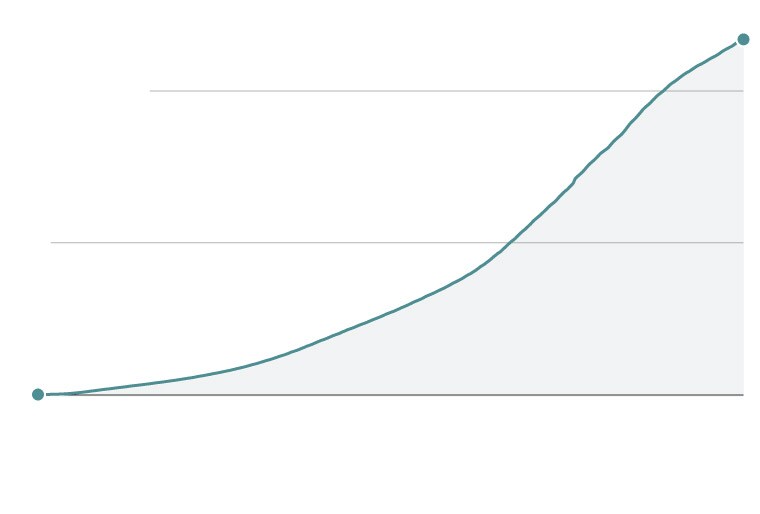

That virus, later named SARS-CoV-2, would slowly reveal its secrets — and proceed to shut down much of the planet, killing more than 2.6 million people in the most disruptive global health disaster since the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Cumulative

reported

cases

Source: Johns Hopkins University

Cumulative

reported

cases

Source: Johns Hopkins University

Why was this pathogen able to do so much damage? Was it the virus itself — its contagiousness, its ability to spread before people knew they were sick, the critical fact that no one on the planet had immunity? How much could be blamed on the slow, chaotic and often scientifically unsound response in so many nations, including wealthy and technologically robust countries such as the United States?

The failings of the pandemic response at the highest levels of government have been extensively documented. But the white-coat experts also struggled, particularly early in the crisis, to understand this stealthy pathogen. Even the scientists and infectious-disease doctors who were primed to think about the possibility of a pandemic tended to underestimate SARS-CoV-2.

More than a year into this global health emergency, Maria Van Kerkhove, an epidemiologist with the World Health Organization, says simply, “We are humbled by this virus.”

Dec. 31, 2019

44 cases,

0 deaths

‘I was wrong about it’

On the final day of 2019, Van Kerkhove received an email with news of a mysterious pneumonia outbreak in a cluster of 44 hospitalized patients in Wuhan. A few details jumped out. Pneumonia: a respiratory disease. Cluster: It’s spreading. And “unknown etiology”: Chinese doctors knew it wasn’t influenza or any other obvious pathogen.

“Pneumonia of unknown cause — China” declared the bulletin the WHO distributed Jan. 5, 2020.

Four days later, Chinese news reports said the illness was caused by a coronavirus. That was the same type of virus that caused SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome, which flared in China in 2003 and killed nearly 800 people worldwide before the outbreak was contained.

[What it felt like to lose time — and all other things coronavirus took away]

“Don your spacesuits, comrades!” Michael J. Buchmeier, a professor at the University of California at Irvine, wrote in a Jan. 9, 2020, email. He was sending a news story to two fellow scientists, Stanley Perlman of the University of Iowa, and Benjamin Neuman of Texas A&M University at Texarkana. They had all worked on SARS.

“This is deja vu,” Perlman replied.

Security staff in protective clothing check the body temperature of passengers at the entrance of a subway station in Beijing on Jan. 25, 2020, during the Lunar New Year holiday. (Koki Kataoka/Yomiuri Shimbun via AP Images)

Security staff in protective clothing check the body temperature of passengers at the entrance of a subway station in Beijing on Jan. 25, 2020, during the Lunar New Year holiday. (Koki Kataoka/Yomiuri Shimbun via AP Images) They were on alert but not rattled. SARS had been scary, but it was contagious only when people were already very sick, and patients could be isolated.

When Chinese scientists uploaded the genomic sequence of this novel coronavirus, it looked strikingly like SARS. Most of the genetic differences “were in places that didn’t seem like they would matter very much,” Buchmeier said. Perlman, Neuman and other members of an international committee of coronavirologists decided it should be given a derivative name: SARS-CoV-2.

Would this become a pandemic virus? Few experts assumed so then. Perlman, for one, figured this new virus would be like SARS1: deadly, but limited in its ability to spread. In a medical journal editorial headlined “Another Decade, Another Coronavirus,” he noted that the virus binds to the same cellular receptor used by SARS1, and people would probably spread it only after becoming symptomatic with an infection deep in the lungs.

“I was wrong about it,” he said.

So was Michael T. Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. He had studied SARS and another coronavirus that caused a disease called MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and knew that patients did not usually become infectious until the fifth or sixth day after symptoms appeared. That meant this new outbreak was containable — surely.

“I was actually relieved and thought this was good news,” Osterholm said.

Susan R. Weiss, a University of Pennsylvania virologist, has studied coronaviruses for 40 years. Even with all her expertise, she says she “naively thought” it would be like SARS and would be contained.

“I personally couldn’t conceive of it taking over the world,” she said. “Maybe I’m not imaginative enough.”

[Stay informed with our guide to the latest pandemic and vaccine developments]

Jan. 10, 2020

41 cases,

1 death

‘This virus still is controllable’

The first to die of the disease that came to be known as covid-19 was a 61-year-old man with chronic liver disease. He had patronized a seafood market in Wuhan where live animals were sold. Other customers had also fallen sick, and the market had been shuttered. But some cases had no link to the market.

“We were really, really keen to know what this virus was,” WHO chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan said. The answer came quickly when Chinese scientists sequenced the virus and on Jan. 11 made public the genetic code. Not only did everyone now know it was a novel coronavirus — and possibly “Disease X,” the term used for a hypothetical pandemic virus — but those initial genomic sequences became the basis for diagnostic tests and vaccines.

On Jan. 13, officials confirmed the first case outside of China, in Thailand. The next day, a team of WHO investigators arrived in China and soon concluded there was evidence of human-to-human transmission. A week later, the first U.S. case was confirmed — a Washington state resident just back from Wuhan.

On Jan. 22, the WHO director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, convened an emergency meeting to assess whether the outbreak constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Too soon, the experts decided.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director general, left, listens to Michael Ryan, head of the WHO Health Emergencies Program, during a news briefing on the coronavirus on Jan. 29, 2020, in Geneva. (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images)

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director general, left, listens to Michael Ryan, head of the WHO Health Emergencies Program, during a news briefing on the coronavirus on Jan. 29, 2020, in Geneva. (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images) “There is still a lot we don’t know. We don’t know the source of this virus, we don’t understand how easily it spreads, and we don’t fully understand its clinical features or severity,” Tedros said.

On Jan. 24, the day the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed 830 cases and 25 deaths, France, Malaysia, Nepal and Vietnam confirmed their first cases, and the United States confirmed its second — a woman in her 60s in Chicago. The virus reached Australia and Canada. In China, the new disease began felling doctors and nurses. Liang Wudong, a doctor who had treated some of the first covid-19 victims, died of his infection.

At a news conference, the Chinese health minister, Ma Xiaowei, announced that people with no symptoms could spread the disease. But he presented no scientific research.

American officials were alarmed and frustrated. Asymptomatic transmission was a terrifying scenario — the recipe for a pandemic. Such a thing should not be mentioned so casually, without supporting data, officials said. In an interview soon after that news conference, Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, made clear his irritation: “That was a major potential game-changer that gets spoken to us in a press briefing. We should have seen the data.”

Jan. 30, 2020

7,818 cases,

170 deaths

‘We are all in this together’

There were still no deaths outside of China. But Chinese scientists were learning more about the pathogen, and what they found was ominous — victims spreading the virus to more than two people on average, and caseloads doubling every 7.4 days in the early days of the outbreak, according to a Jan. 29 report out of China published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The WHO on Jan. 30 revisited the proposal to declare a global health emergency. There were at least 82 cases in 18 countries outside of China, including seven individuals with no history of travel to China. The experts decided they had seen and heard enough, and declared the emergency.

“We are all in this together, and we can only stop it together,” Tedros said at a news briefing.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first domestic case of human-to-human transmission.

It wouldn’t be the last.

Feb. 4, 2020

23,898 cases,

492 deaths

‘20 times more infectious and 20 times less lethal’

The world became transfixed by the plight of the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship with a coronavirus outbreak — 10 cases at first — as it sailed in Japanese waters. The ship went into quarantine in the port of Yokohama. Passengers were told to stay in their rooms. There were many Americans on board. A team of U.S. infectious-disease experts flew to Japan and boarded the ship while wearing personal protective gear. They were led by two doctors, James Lawler and Michael Callahan, with extensive experience with outbreaks, including Ebola.

What they discovered shocked them: Even people who had stayed in their rooms, doing everything to prevent infection, were coming up positive. When Lawler and Callahan returned to their hotel, they called their superiors with a grim message: It’s everywhere.

“James and I were pretty certain we had a pandemic when we saw how transmissible it was on the Diamond Princess,” Callahan said. “I presumed it to be like SARS1. The only thing I got wrong was it was 20 times more infectious and 20 times less lethal. In February, everyone missed that.”

A passenger is seen in her cabin of the quarantined Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan, on Feb. 20, 2020. (Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images)

A passenger is seen in her cabin of the quarantined Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Yokohama, Japan, on Feb. 20, 2020. (Tomohiro Ohsumi/Getty Images) Feb. 15, 2020

69,052 cases,

1,666 deaths

‘I don’t think I know a single person who would anticipate it would get to this magnitude’

H. Clifford Lane, deputy director for clinical research and special projects at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, flew to Beijing from Tokyo on Feb. 15. He saw how the Chinese, with painful memories of SARS, avian influenza and other emergent diseases, were bringing the virus under control through aggressive action. They had built a 1,000-bed temporary hospital in Wuhan in just 10 days. The government forcibly isolated not only the sick but also their close contacts.

“The country as a whole was at war with the virus,” Lane says.

This clearly could become a pandemic — a word increasingly murmured by other American experts studying the numbers and modeling the outbreak. And yet Lane still did not imagine he was seeing the beginnings of a pandemic that could inflict death and misery on a scale normally associated with a world war.

[U.S. coronavirus cases and state maps: Tracking cases, deaths]

“At that point in time, if you had said you would have a global pandemic, I don’t think I know a single person who would anticipate it would get to this magnitude,” Lane said. “I certainly didn’t.”

The subsequent report from the joint WHO-Chinese visit established many characteristics of the virus that remain unchanged. It was a zoonotic virus, closely related to a bat coronavirus strain. It had mutated very little between December and February. The disease’s severity ranged from mild to severe, with the elderly most vulnerable. It appeared to spread easily in households and other closed settings such as prisons and long-term-care facilities. The report played down the likelihood of airborne spread — a subject that would become controversial.

An aerial photo shows excavators at the site of a hospital being built to treat coronavirus patients in Wuhan, China, on Jan. 24, 2020. (AFP/Getty Images)

An aerial photo shows excavators at the site of a hospital being built to treat coronavirus patients in Wuhan, China, on Jan. 24, 2020. (AFP/Getty Images) At the other end of Eurasia, infectious-disease experts gathered Feb. 15 in Munich for a town hall to discuss the virus. Among the attendees: J. Stephen Morrison, director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Also on hand: Mike Ryan, executive director of the WHO Emergencies Program, and Qin Gang, vice minister of foreign affairs for the People’s Republic of China.

The atmosphere was tense — one of many moments in the international dance of health diplomacy as WHO experts were preparing to visit China.

Morrison noted there were 67,000 confirmed cases, dispersed among 25 countries. He raised the possibility that the true numbers were much larger.

“We cannot afford to get it wrong,” Morrison said. “Are we moving into a global pandemic?”

Ryan’s response was quick: “We’ll have to get you to write the movie script for the next disaster movie.”

Ryan added, “The present and the future you paint is obviously one that can come to be, but I think much of that is avoidable.”

March 1, 2020

87,916 cases,

3,040 deaths

‘Information was constantly evolving’

It came to be. Covid-19 exploded in Northern Italy, collapsing the health-care system there. Travelers carried the virus to the U.S. East Coast. Ambulance crews in the early hot spots of New York and New Jersey traded stories about how spooked they were by cases they were seeing.

Paramedics and EMTs described being called to homes and finding someone who was sitting up and talking — but who had oxygen levels so low they would normally be dead. And how there was an unusually high number of people dead on arrival, their relatives saying they had seemed not very sick several hours before.

Mount Sinai Hospital radiologist Adam Bernheim studied images sent from China showing lung damage in covid patients. The pattern was unlike tuberculosis or any other respiratory disease the New York physician had seen: white, round-shaped spots clinging to the edge of patients’ lungs. He and a colleague called them “peripheral ground-glass” in a scientific journal.

He knew the wave was coming, but he couldn’t imagine how hard it would hit.

Patients flooded into hospitals with issues that had been simply footnotes in reports from China and Europe. Hospitals were prepared for respiratory distress and the covid-19 “cytokine storm” of inflammatory responses. They did not expect so many patients with multisystem organ failure: a hardening of the walls in the heart, acute kidney failure, blood clots in the brain.

“It was terrifying to see the numbers take off,” said Craig R. Smith, a surgeon at Columbia University Medical Center in New York. “If you plotted that rate of growth, this was going to be the biggest epicenter the world had ever seen of the coronavirus.”

The early days were full of medical guesses and improvisation. Doctors shared anecdotes in hundred-person Zoom meetings. Modern medicine thrives on flow charts, formulas and official guidance for patient care, but many of the preparations made for the coronavirus were wrong.

Smith described “a lot of hopeful things being tried, a lot of misinformation, a lot of superstition.”

“Everybody was trying really hard,” he said. “It wasn’t perfect, but you can’t expect perfect in chaos.”

Doctors argued with each other over basic aspects of care such as when, exactly, to put a patient on a ventilator. Some specialists decided to give patients hydroxychloroquine — the drug touted by President Donald Trump as key to ending the pandemic — drawing ire from colleagues who said there was no evidence it helped. Proning — turning patients on their stomachs — and delaying intubation appeared to lead to better outcomes.

The sudden deaths reported by ambulance crews, scientists later speculated, were probably caused by heart attacks and strokes associated with clotting. And the peculiar phenomenon of people who had very low blood oxygenation but were not short of breath — known as silent hypoxia — signaled that the air sacs in covid-19 patients’ lungs were not reacting as in a typical pneumonia.

Coffins arriving from the Bergamo area of Italy are unloaded from a military truck that transported them to a cemetery near Milan on March 27, 2020. (Claudio Furlan/LaPresse via AP)

Coffins arriving from the Bergamo area of Italy are unloaded from a military truck that transported them to a cemetery near Milan on March 27, 2020. (Claudio Furlan/LaPresse via AP)  A CT scan from March 2020 shows lungs of a 65-year-old man in China with covid-19. Pneumonia caused by the coronavirus can show up as distinctive hazy patches on the outer edges of the lungs, indicated by arrows. (Mount Sinai Hospital via AP)

A CT scan from March 2020 shows lungs of a 65-year-old man in China with covid-19. Pneumonia caused by the coronavirus can show up as distinctive hazy patches on the outer edges of the lungs, indicated by arrows. (Mount Sinai Hospital via AP) As the country headed deeper into spring, reports from hospitals in the pandemic’s epicenter of New York became increasingly dire. In daily missives that went viral, Smith described a hell.

A “10-fold increase in cases in just one week,” he wrote March 21. “To think we could mimic Italy seemed risible a week ago. Not today.”

Smith would later describe how one of those early patients died: “A man falls ill. He says goodbye to his wife on his way to an ICU. After three weeks on a ventilator, the man passes away, alone. The man’s children are spread across the country. He waits in a refrigerator truck for the family to make arrangements.”

Covid-19 has turned out to be much more than a simple respiratory disease. Multiple organs can fail. People can get mildly ill and then seem to be on the mend — only to suffer a second-week crash.

Paradoxical as it may sound for a pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2 was not particularly virulent — meaning, it didn’t sicken people the way deadlier viruses such as SARS1, MERS or Ebola did. People remained mobile. For several days, the virus would incubate in their bodies. Then it would begin to shed, infecting other people even before symptoms appeared. Peak viral shedding was right about the time the person noticed a fever, cough, fatigue and body aches.

“One of the things we have learned is that experts here almost every step of the way have been wrong,” Bernheim said. “I learned to stop making predictions.”

[A look back one year after the WHO declared the coronavirus a pandemic and changed how we live]

March 11, 2020

126,250 cases,

4,720 deaths

‘Concerned that negative is not really negative’

America shut down rapidly. The National Basketball Association canceled its season March 11, and other sports followed. Schools, restaurants, gyms, hair salons, office buildings — everything closed, the streets emptied, and people sheltering at home found themselves forced into amateur epidemiology, guessing at what remained safe to do as the invisible threat circulated.

Some early research caused panic, including experiments suggesting the virus could remain viable for 24 hours on cardboard and up to three days on plastic and stainless steel, prompting fearful shoppers to wipe down their groceries.

At 5 a.m. March 19, University Medical Center in New Orleans reported its first covid-19 death: a 44-year-old African American man who came in with a fever and died three days later. His doctors had requested an autopsy, but the hospital leadership — like others across the country — was hesitant given the potential risk of transmission.

“No one was jumping up to do it, so I was like, ‘I’ll do it,’ ” pathologist Richard S. Vander Heide said. Curiosity had gotten the better of Vander Heide, who had started out doing autopsies on HIV patients 20 years earlier.

A commuter walks up a staircase at the Oculus transportation hub in New York on March 17, 2020. (Demetrius Freeman/Bloomberg News)

A commuter walks up a staircase at the Oculus transportation hub in New York on March 17, 2020. (Demetrius Freeman/Bloomberg News) When he pulled out the lungs, he was both terrified and intrigued to find something he had never seen before — hundreds of microclots all over them. The discovery of the abnormal clotting — which was being reported at other hospitals — became one of the turning points in medicine’s war against the virus. It led to the standard use of blood thinners and platelet medications believed to have saved many lives.

After autopsy No. 5, Vander Heide noticed another alarming pattern: that lung damage was similar in both coronavirus positive and negative patients. He wondered about the accuracy of screening and testing procedures. He typed out a message to the chief medical officer on his iPad. “Concerned that negative is not really negative. Pulmonary hemorrhage in the last 5 autopsies despite Covid status.” The senior staff scrambled to get the message out to the front lines.

The CDC had told doctors to be on the lookout for flu-like symptoms of fever, cough or difficulty breathing. It turned out many of those infected had none of the above. Instead, they reported loss of smell and taste, and gastrointestinal issues such as nausea and vomiting, or headaches.

On March 21, an alert appeared from the United Kingdom about loss of smell being a potential marker of covid-19 infection. It wasn’t until April 26 that the CDC added anosmia — the loss of smell or taste — and five other symptoms to its checklist.

March 17, 2020

198,245 cases,

8,082 deaths

‘This goes into the air’

Lea Hamner, an epidemiologist in Skagit Valley, Wash., remembers her colleague racing across the room March 17 and handing her a note on which she had scribbled the words “chorale” and “positive test — 24 people.”

A week earlier, 61 members of a church choir had met indoors for a rehearsal. The CDC would later report that 52 of them tested positive for the coronavirus or were probable cases.

Hamner’s team realized it had a superspreading event on its hands. The 10 staffers in the office divided up the roster and worked the phones. A huge number from the choir had symptoms: runny noses, headaches, fevers. And as Hamner mapped where everyone was in the room, some things didn’t make sense according to what she had heard about transmission.

The WHO and CDC had emphasized infection occurred through respiratory droplets that act like canons coming from people’s mouths and noses and fall to the ground no more than about six feet away.

Lea Hamner, an epidemiologist in Skagit Valley, Wash., outside the Skagit County offices on March 3. (Stuart Isett for The Washington Post)

Lea Hamner, an epidemiologist in Skagit Valley, Wash., outside the Skagit County offices on March 3. (Stuart Isett for The Washington Post) But, Hamner recalled thinking, “The sheer number of people who got sick — it didn’t seem logical that all 52 people all got within six feet of one person. You can’t rule out anything, but it didn’t seem likely.”

Jose-Luis Jimenez, a University of Colorado professor who studies aerosols, investigated the case and became a vocal proponent of the theory that the virus was spreading through aerosols. He emailed his friends and family March 30 — “this goes into the air” — and urged them to wear good masks.

There were other highly publicized incidents of possible aerosol transmission, but scientists continued to debate the issue for months. Jimenez and 238 other experts eventually took their case to the WHO. On July 9, the WHO updated its guidance to acknowledge that airborne transmission in indoor locations with poor ventilation “cannot be ruled out.”

The CDC followed suit later in the year, saying that while most infections happen through close contact, the virus can spread “via airborne transmission under special circumstances.”

A choir practice held at the Mount Vernon Presbyterian Church in Mount Vernon, Wash., on March 10, 2020, as the coronavirus was spreading in Seattle, left dozens of people infected with covid-19. (Stuart Isett for The Washington Post)

A choir practice held at the Mount Vernon Presbyterian Church in Mount Vernon, Wash., on March 10, 2020, as the coronavirus was spreading in Seattle, left dozens of people infected with covid-19. (Stuart Isett for The Washington Post) March 25, 2020

472,034 cases,

21,497 deaths

‘We’re still in the thick of it’

On March 25 — as the U.S. death toll topped 1,000, a number that made people gasp but now seems tiny compared with the 525,000 who have perished since — the Trump administration acknowledged it needed help from outside experts. Representatives from the major U.S. medical societies were summoned to Federal Emergency Management Agency headquarters on C Street SW in D.C. with barely a day’s notice.

In marathon 10-hour meetings in which attendees only had time to grab bottled water and snacks from vending machines, Adm. Brett Giroir, the testing czar for the administration, directed experts from government, the military, academia and private hospitals to come up with attack plans to stop more people from dying.

Lewis J. Kaplan, a critical-care surgeon from the University of Pennsylvania who is president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, found himself in a room with about 20 other experts and several types of ventilators, tubing, connectors and other parts. The setup reminded him of a grade school science challenge with vintage Erector toy sets. Their mission: to figure out a way to put two patients on one ventilator.

Rooms are set up for a makeshift hospital at the Javits Center in New York on April 1, 2020. (Demetrius Freeman for The Washington Post)

Medical workers in protective clothing move the body of a deceased patient to a refrigerated overflow morgue outside the Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn on April 2, 2020. (Angus Mordant/Bloomberg News)

EMTs load a gurney into an ambulance outside the home of a coronavirus-positive patient in North Bergen, N.J., on April 17, 2020. (Bryan Anselm for The Washington Post)

TOP: Rooms are set up for a makeshift hospital at the Javits Center in New York on April 1, 2020. (Demetrius Freeman for The Washington Post) BOTTOM LEFT: Medical workers in protective clothing move the body of a deceased patient to a refrigerated overflow morgue outside the Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn on April 2, 2020. (Angus Mordant/Bloomberg News) BOTTOM RIGHT: EMTs load a gurney into an ambulance outside the home of a coronavirus-positive patient in North Bergen, N.J., on April 17, 2020. (Bryan Anselm for The Washington Post)

With past respiratory viruses, patients often needed only two to eight days on a ventilator, but covid-19 patients sometimes appeared to need them for two or three weeks, or more.

“Everyone knew this was a serious problem, and everyone had in the back of their mind that the person who may need this therapy may be you,” Kaplan says.

One detail of that day stood out: Everyone was physically distanced but few were wearing masks. It would be more than a week before the CDC recommended everyone wear a mask.

What was left unsaid was how different things might have looked if these meetings had been held a couple of months earlier.

“In retrospect, we were totally wrong for not being better prepared,” Kaplan said.

March 2021

117 million cases,

2.6 million deaths

‘We have underestimated definitely the staying power of this epidemic’

And now a year has passed.

“It’s March of 2021,” Van Kerkhove, the WHO epidemiologist, says, realizing the date as she gives an interview on the first of the month. “I can’t believe it.”

The pandemic continues. For how long? At this point, anyone giving a confident answer is guilty of hubris.

Tremendous progress with vaccines has been coupled with the emergence of mutated variants of the virus. The variant news was a reminder the virus is not static. It evolves as it adapts to its new human host and collides with the human immune system. Random mutations can enhance the “fitness” of the virus, making it bind better to receptor cells, or evade antibodies.

Maria van Kerkhove, an epidemiologist with the WHO, speaks during a news conference at the European headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva on Jan. 29, 2020. (Martial Trezzini/Keystone via AP)

Maria van Kerkhove, an epidemiologist with the WHO, speaks during a news conference at the European headquarters of the United Nations in Geneva on Jan. 29, 2020. (Martial Trezzini/Keystone via AP) Why hadn’t SARS1 mutated the same way? Actually, it did, says Buchmeier, the UC-Irvine professor: In 2003, it splintered into four lineages before it was contained. “We never saw the full potential of SARS1, because SARS1 came and went so quickly,” he said.

The world this time gave SARS-CoV-2 plenty of opportunity to show its potential. The spring wave of infections that hobbled the global economy was followed by an even more protracted surge in the fall and winter.

“When you have an out-of-control pandemic affecting hundreds of millions of people, there is just an unbelievable amount of viral replication happening around the world, so the virus has that many opportunities to evolve,” said Jonathan Li, a virologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“I think we have underestimated definitely the staying power of this epidemic,” he said.

Much remains unknown, or unclear. Basic questions involving transmission, disease severity and even the origin of the virus remain under investigation.

And although this is a virus related to the coronaviruses that circulate in bats, no one knows precisely how, when and where a mutant coronavirus first jumped into the human species.

Another mystery: Many people suffer from “long covid,” with symptoms persisting for months and threatening to be chronic. That is the subject of newly launched research at the National Institutes of Health.

The global scientific community accelerated its normal pace of research, sharing data on public websites and vigorously reviewing and correcting the findings of others. The virus and covid-19 have been meticulously described in more than 13,700 research papers published on the online servers medRxiv and bioRxiv, the gateway to peer-reviewed journals. And knowledge accrued over many years before the pandemic helped pave the way for the production of coronavirus vaccines in record time.

A passenger waits at the Termini Central Station in Rome on March 9, 2020, after Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced the closure of the Lombardy region in an attempt to stop the spread of the coronavirus. (Antonio Masiello/Getty Images)

A passenger waits at the Termini Central Station in Rome on March 9, 2020, after Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced the closure of the Lombardy region in an attempt to stop the spread of the coronavirus. (Antonio Masiello/Getty Images) The pandemic in many ways brought out the power of the scientific method.

Postmortems, when they are written, will note that experts had been warning of a viral pandemic for many years. This was not a “black swan” event, not a “perfect storm.” A viral pandemic is an obvious vulnerability in this age of economic globalization, when nearly 8 billion people and their parasitic viruses are highly networked and mobile.

Van Kerkhove says she doesn’t think SARS-CoV-2 is “the Big One.” The science, she says, must press on.

“We won’t stop until this is over,” she says, “and unfortunately there will probably be something else.”

Design by Christian Font. Art direction by Suzette Moyer. Photo editing by Bronwen Latimer. Story editing by Stephen Smith. Copy editing by Karen Funfgeld.