The stile world cup started as a joke, but now has 120 contenders

It all started three years ago as an antidote to the angry, inflamed opinions on Twitter. I just thought, let’s make something nice here so I started posting photos of stiles that I’d taken on my daily fell runs in the Lake District. I chose stiles simply because I have to stop at them when I run. They make you pause and look around and I like that. Once I’d started posting the pictures, it grew into something. People started sharing their own photos, locally but also in the Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand and more. It’s a small, low key-thing to do, but heartening too.

When the third lockdown was announced, my son joked that I should hold the “stile world cup”. I’ve now got about 120 photos and today I’m starting a series of Twitter polls to find a winner.

All sorts of people have their little interests: there is a farmer and Guardian Country Diary writer in this area, Andrea Meanwell, who takes photos of postboxes. There are people taking photos of bridges, and windows. Usually they are people with some knowledge of their subject. I just wanted to show that you can be kind and share things with other people. I can’t believe how excited people have got about it – I guess they have the time and energy right now. It’s something they can do locally, within the confines of lockdown. I have a mate on the local community radio station who’s going to mention the Twitter polls.

When we’re not in lockdown I run for hours, usually early in the morning. The great thing about fell running is that you can cover a lot of ground and be back by 9am. During lockdown I can’t go as far but I can still run out of my garden gate and up a hill, Benson Knott, to views of Pennines and Morecambe Bay. It’s just the local hill – but it’s quiet and feels remote.

Mark Squires (on Twitter)

Hornbeam trees are gnarly old weirdos and I love them

People rave about oaks and beeches, but as lockdowns restricted our outings to walks in the woods near our home, I became fascinated with a more eccentric species: the hornbeam.

While most tree trunks stick unimaginatively to growing vertically, hornbeams in Epping Forest adopt all kinds of exuberant angles: 45 degrees to the forest floor is not unusual; some – still green and growing – lie prostrate on the ground or even across a stream, like a diva in mid-tantrum. On poor soil, I learned, hornbeams put down deep roots and remain upstanding, but in south-east England’s rich clay – OK, sticky mud in winter – there’s no need for such efforts and their roots descend barely 35cm, leaving an unsure footing, and crazy leans.

Hornbeams are often mistaken for beeches, but to me they’re more elegant, with grey fluted bark spiralling up into the canopy. When Covid hit last March, we walked among hornbeams heavy with catkins. In summer their dense, serrated leaves provided welcome shade. But autumn is magical in a hornbeam wood: leaves are turning yellow, and tiny nuts have ripened in three-lobed leafy bracts. Every gust of wind loosens a snow-globe whirl of tiny golden helicopters. Now, in mid-January, reddish leaf buds are already reappearing.

In hitherto unknown (to me) corners of the forest, I notched up favourite specimens. Older hornbeams are the real weirdos – trunks a writhing mass of grooves and sinews, like something artist Roger Dean might have dreamed up for a 1970s album inspired by Lord of the Rings. Others are more Stranger Things – one with a 90-degree bend in its trunk seems an alien beast stalking the bank of the Ching brook.

With their hard wood being valued for axles, cogwheels and chopping blocks as well as fuel, hornbeams were planted across southern England and the Midlands. Look out for them in mixed woodlands, and in parks and cemeteries, where extra space allows them to form mighty broad-oval crowns.

And if lockdown desperation has you reaching for old films, check out the Black Knight scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. It was shot in Epping Forest, in a spot encircled by guess what sort of gnarled old trees.

Liz Boulter

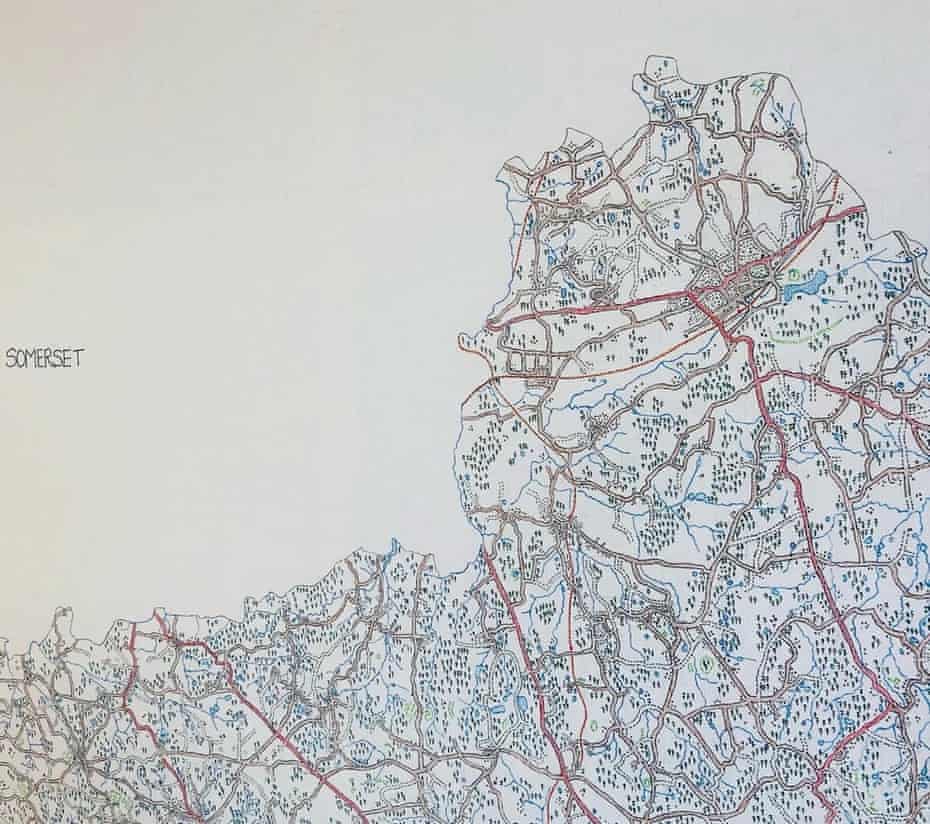

I drew a map of Dorset – but it’s too big for my house

A few years ago, I started walking, like, every day – and I don’t even have a dog. For me, living in the depths of Dorset and a single mum of three young boys, it became an easy pastime and an escape from the daily screams. I loved it, still do. My academic history includes a Master’s in Landscape Archaeology and my career, before children, was in cartography. I combined it all and wrote about my walks. I’d investigate the area, and discover legends, mysteries, true stories and the evidence for them in the landscape.

I drew maps of my walks, and loved the different perspective they created. Displaying only roads, railways, buildings, trees, rivers and earthworks, they showed the present day, but they also echoed history. I imagined a bigger map, of the whole of Dorset, and what better time to do it than in lockdown?

Using careful maths, a metre rule, patience, space and strict rules for the boys to keep their distance, I began, starting with a grid covering the whole of Dorset, in four quarters. Using a combination of Google and Ordnance Survey maps and my own knowledge, the hand drawn map grew, every metre of the landscape carefully marked out. Hillforts appeared, Roman roads cut through countryside and river paths marked out the valleys. Tracks hinted at the old medieval droves, now little more than muddy lanes connecting ancient villages. The whole process has encouraged me to explore more, to go and find that lump, bump or hump in real life. If a picture tells 1,000 words, this map speaks millions, even if it’s just to me. Its future I am yet to learn – I have no wall big enough. Maybe a pub, somewhere in Dorset?

Catherine Speakman (on Twitter and Instagram). Read more on her website tessofthevale.com

Spoon carving is meditative – though there may be blood

I decided that spoon carving would be the perfect hobby last autumn, just as the nights were drawing in and Newcastle was plunged into lockdown again.

I had recently started my own online journal, Inkcap, about nature in the UK, and the project had awakened an old tendency to work until bedtime. I was feeling constantly stressed, and though I was regularly writing about nature’s calm effects, I was reluctant to spend the cold evenings in city parks. Spoon carving seemed like the perfect compromise: it would force me from my computer and bring nature into my cosy home.

For Christmas, I got a special whittling too called a sloyd knife. Since then, I have carved almost every day, learning about trees and getting a feel for the wood. I signed up to Spoon Club, which has a library of video tutorials that guided me through the knife grips and axe wielding. It’s unusually meditative for an activity that carries a real risk of drawing blood.

It has also inspired me to get out of the house. If you’re going to carve a spoon, you ideally need greenwood, which is fresh and soft with sap.

My first spoon – a teaspoon – was carved from the fresh trimmings of a hedge in Whitley Bay, a coastal town close to home. The hunt for material was interrupted by seals bobbing in the waves by Saint Mary’s Lighthouse.

But I wanted something bigger. The following weekend, I went on a quest to the deer park in Bishop Auckland (not far from the now-famous Barnard Castle). This 150-acre wood pasture was created by County Durham’s prince bishops over 800 years ago, when it would have provided them with charcoal and animals to hunt. In future, I’m going to source my wood from local tree surgeons, but I didn’t think they would begrudge me a small, storm-felled branch.

Sophie Yeo, environmental journalist

My card hobby cleans up plastic, gets me out – and is now a business

On World Rivers Day in September 2019, I joined a Southwark beach clean and was astounded by the amount of micro-plastic, sequins and beads we collected in a short time. I didn’t know that that day would inspire a new hobby – crafting cards using my finds – and turn out to be a lifesaver during lockdown.

I had made a card for my sister’s wedding with things I found on that first trip (she’s lived plastic-free for two years so it was apt) and when lockdown struck, although I couldn’t go out with a group, I decided to go out again on my own.

I would wander along the Thames with gloves and a bag, collecting tiny pieces of plastic and rubbish from the banks – and then take it home to turn into works of art. I could always see shapes I would turn into illustrations with relevant captions.

It gave me something to do when I was furloughed: doodling and playing was really positive – a kind of therapy really. Being outside by this huge river, smelling the water and spotting wildlife had a calming effect. And hunting for plastics is meditative – you have to pay attention and look carefully at your surroundings.

It actually helped me connect with a new community too. I’d just gone through a break-up, had moved into a new area and was feeling quite alone, so I made cards with positive messages and sent them to everyone in my block. It helped break the ice – and actually led to some great new friendships.

Later in the summer, I put some of my cards on an Etsy online shop and set up a business, Washed-up Cards. I regularly collect plastic on my walks – and am currently working on a Valentine’s Day collection.

This hobby has been positive in so many ways: it helps clear up plastic, gets me outside and is now even a little business. I don’t know what I’d have done without it.

Flora Blathwayt