The sun is slowly rising over the Atlantic and I sit watching from the house I have rented overlooking dunes on the small Portuguese island of Armona. The sound of fishing boats heading out marks the pre-dawn, a time known as the blue hour, now a time when many are awake, having thrashed the bedding during another fretful pandemic night. I try to meditate and do breathing exercises to settle myself down. “It will be all right,” I say. And the sun says it back.

I hadn’t intended to go and live on my own on an island for Covid’s second wave. But I spent the first lockdown in my flat in Spitalfields, London, making a podcast called On the Ground for the BBC about my time as an embedded journalist working for the Guardian during the invasion of Iraq. It was a tough, traumatic experience, and isolation made it hard. But what made it even harder was the relentless noise of building works across my tiny cobbled street as excavations began to create a basement for what will become the British art duo Gilbert and George’s new gallery.

As September unfolded and Nicola Sturgeon announced that we could not go to other people’s homes or get in their cars, I knew that a family Christmas in Scotland would be cancelled. I have no ties in midlife. No partner, no children – just family, friends and a little godson, and I began to sense that I would soon not be able to see any of them for a while.

In Glasgow, we say “I felt it in my watter”, and I did. I knew I couldn’t do a lockdown again in my flat and so, four days later, I was on a plane to Faro, and from there to a house in Olhão, a fishing town that I have come to love over the past decade or so. I had been there last March – in those sudden, terrifying days when we realised this disease was truly coming – working on a story about the food of the eastern Algarve. The trip was abruptly cut short and I flew home and into lockdown.

Last September, we could travel again as long as we self-isolated for two weeks once back in the UK, so I stocked up my cupboards for my return, which I thought would be in a couple of months, and bought a one-way ticket.

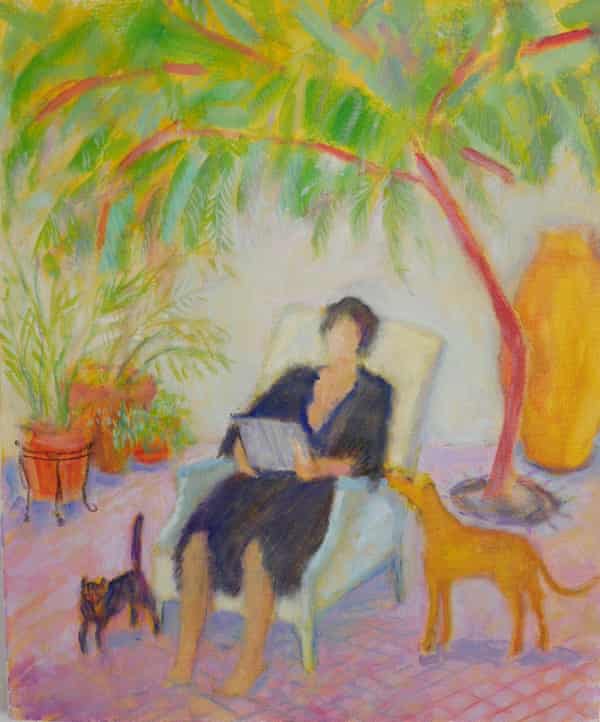

In Olhão, I stayed with a British painter, Fiona Gray, and spent days writing in her wondrous plant-filled courtyard, where she captured an image of me frowning and puckering my lips, as I do, over my laptop. A new tenant had booked her space for the following month and so I moved on, to a house I soon discovered was next to some building works – the very thing I had sought refuge from. The 7.30am grinding of a cement mixer drove me away, to the stillness of a holiday island out of season.

Armona is one of five barrier islands in the Ria Formosa that protect the mainland from the full force of the Atlantic. It has no cars, just bicycles and a few quad bikes used to move building materials and take away the rubbish. Three shops sell essentials and alcohol, and there are six restaurants, a cafe and a beach bar. In the peak of summer, there are 13 ferries a day, but in winter there are just four.

In high season, the air hums with holiday sounds: the flap of flip-flops, the shouts of children playing, people splashing in the sea, families eating alfresco on the terraces of the little houses and outside the chalets of Orbitur camping park. The concrete path – the passadeira – through the heart of the island is filled in summer with people heading to the wooden boardwalk that leads to the vast beach on the Atlantic side, or back to the ferry.

But in winter, there is quiet. Most of the houses are shuttered. A small community remains: Portuguese people, many of them older, and foreigners who fell in love with the place and decided to stay. Now, the passadeira is spray-painted with arrows reminding pedestrians to socially distance.

When I arrived on Armona, I stayed in a house on the bay, where the sun blazed as it waned. I became friends with my neighbour, António, who brought me 13 fresh sardines when I arrived. I soon learned that this was in return for access to running water and turning my nose away when he emptied his toilet bucket out on the turning tide.

His white hair bobbled up in a tiny ponytail, his fingernails long and curled, António – nickname Tó Luís – is one of the people who live on Armona with very little. His shack has just a bed. Years ago, Tó Luís went to prison for three years for stealing 20 escudos – about 10p. He fought eviction from Armona, won sitting rights and now he gets by. Kindness on the island allows him his fresh fish, a kindness he kept extending to me.

In the early winter, I would go to Olhão to shop in one of the best markets in Portugal, eat lunch with friends and run for the last ferry at 5pm. I reassured my parents that I had made the right choice: the Covid cases in the town were not high and there had been none on Armona.

I recorded the sounds of the island and sent a series of audio postcards to a very dear old friend who was ill with Covid and in intensive care – trying to take him away for a few moments to the world I know I am lucky to be living in. The crashing waves, the wheels of shopping trolleys as people go back and forth to the ferry, the bom dia, boa tarde or boa noite – good day, good afternoon or good night – called out in greeting depending on the time of day. The few aeroplanes coming in and out of nearby Faro airport. The birdsong at dusk as hundreds of sparrows gather in eucalyptus trees. I whispered to him, sometimes through tears. And felt guilty. As I do now, being here and writing this.

On Christmas Eve (which, as in most of Europe, is more important here than Christmas Day), Tó Luís gave me a kind-of Christmas tree – an old coffee jar filled with sand and pine branches and yellow flowers, and decorated with milk-bottle tops and cotton wool snow. I cried. On Christmas Day, I briefly jumped into the sea and ate a lunch of Belgian stew and chips on the terrace of Lanacosta restaurant, overlooking dunes and the ocean.

On 31 December, I moved again, to a new house at the end of the passadeira, a glorious place with vast floor-to ceiling doors that bring in so much light.

The clack, clack, clack of the dominoes hitting the Formica table and the soft shuffle of the tiles being mixed up, the laughter and jokes of the group of men who gathered every night to play in the Armona 4 bar and grill were soon to be silenced. Over Christmas, Portugal went in to what president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa later termed “laxism”. Restrictions were lifted and families came together – just as the British variant emerged here.

It was catastrophic and Covid surged. In January, Portugal’s deaths totalled 5,576, which was, at the time, nearly half the country’s total so far in the pandemic. A state of emergency was declared and all but essential services closed down on 14 January. Flights were cancelled and the UK put Portugal on the red list, which meant anyone landing would immediately be taken to hotel quarantine at a cost of £1,750. My “watter” and my wallet decided to sit it out. My “watter” was right: Portugal was removed from the red list on 19 March, but there are no flights to the UK.

I embraced the winter, the coldest the Algarve has experienced in 10 years. The storms threw a lot of plastic, a few face masks, even a television set on to the beach, and this brought another kind of sadness. But I learned about the tides, and bought conquilhas – sweet little bivalves that are better than any clams I have eaten – directly from the men who dig them out of the sand when the sea has gone out – backbreaking work. I delighted in spring emerging, watching the glorious yellow mimosa bloom all across the island and cutting flowers to stick in the jars I have collected.

I have spent months on my own, but I have friends here now. Feathers, the grey and red parrot that whistles at me when I walk by. Pam and Zé Pardo, who own the Armona 4 by the ferry pier and hosted a little lunch for me on my birthday in February, where Zé got out his guitar and we sang Carole King’s You’ve Got a Friend. Pam is now my “island mum”. There’s Gil, who waves every single time he passes my house on his quad bike, and Leonor, who, with her green cart, sweeps the passadeira and empties the bins and always cheerily says hello and asks how I am.

And then there’s Ulrike who, because of Covid, had to leave India and the charity she founded to change the lives of poor village children by building a skateboard park, which is called Janwaar Castle. We take long walks together, Ulrike and I. I like to cook for her. And every day she says, “Life is good.” Which is so incredibly heartening. We know we are lucky. To be here, and to be here still.

Tomorrow is Easter Sunday, Páscoa. Another viscerally important time for families to come together in Portugal. But, having learned from the laxism of Christmas, and with strict lockdown seeing cases plummet as fast as they rose, the government pretty much banned movement from 26 March and told people to stay at home for 10 days.

But on Easter Monday, things will begin to ease. Restaurants can open if they have an outside terrace, and tables will be limited to four people. On Armona, where everyone knows that just one case would devastate the island, there is a feeling of hope. The paint cans are out. The restaurants are refreshing and refurbishing. A new ice-cream shop has been created next to Armona 4, which has overhauled its roof terrace; and the once dimly lit “big” shop has new owners, who have cut out new windows, got in more stock and put a fancy sign above the door: O Cantinho da Ria (translating roughly as Estuary Corner).

Tomorrow there will be more than a few prayers. That this will mark the end of lockdown, that visitors will return to the island, that flights will begin again. And, eventually, I will have to return home.