The river crossing from South Woodham Ferrers to Hullbridge looks like a scene from a John Constable painting: two men in shorts and big boots are washing down their horses in the river as Duncan from the yacht club rows me across the swirling tidal waters of the River Crouch. I’m heading across to meet other walkers participating in the Beach of Dreams project, a 500-mile walk around the Suffolk and Essex coasts. Duncan points downriver. “That’s Brandyhole Reach, where the smugglers would bring their barrels to hide from the excisemen.”

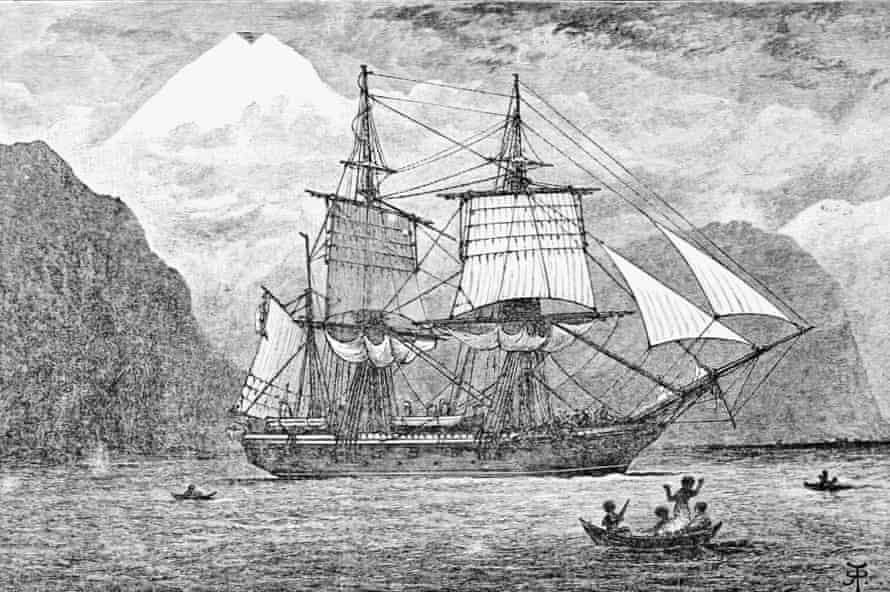

We are a few miles upriver from Burnham-on-Crouch on the Essex coast and under my breath I’m singing Billericay Dickie by Ian Dury, the only song I know that namechecks Burnham-on-Crouch. Duncan lets the boat drift downstream a little, then starts to pull hard for the far side. In 1845 the battle between local smugglers and the customs men had caused the Admiralty to moor an ageing ship on the River Roach, a tributary of the Crouch, at Paglesham. The crew were all brought in from outside as no one local could be trusted. The ship was a creaking hulk that had seen better days and was at the end of her life. Her name was HMS Beagle.

At that time the significance of the ship had yet to become fully apparent. Darwin’s book On the Origin of Species was still 14 years away from publication, but a revised edition of The Voyage of the Beagle in 1845 had started to hint at evolution as an answer to all that the naturalist had discovered. As for the Beagle, it was simply a Napoleonic-era 10-gun brig whose day was done.

Our walk leads us down the sea wall towards Paglesham with a few loops into the farmland nearby. There are some lovely traditional Essex houses here: neatly painted clapboard cottages whose lawns are well trimmed and lined with hollyhocks and roses. On the south-facing slopes across the river are vineyards that produce award-winning wines. Essex is full of surprises: the coastal towns and villages look like places where tradition and heritage matter. I find restored traction engines on Mersea Island; up St Osyth Creek, an 1894 Thames barge is being repaired; in Burnham, Fiona is raising money for Dunkirk veteran boat the Vanguard, and shipwright Edward is working on an elegant teak-built 1938 cruiser. Essex is an industrious hive of heritage.

Late in the day I push on alone, leaving the others far behind, and come around the long curling sea wall to Paglesham. I’m wondering what happened to the Beagle; the Department of Media, Culture and Sport is supposed to have declared its last resting place a national monument. When I arrive, however, all I see is a few rusting ships and a parcel of saltmarsh cordoned off by a flimsy fence. There are no signs. Is that where the Beagle ended her days? I know that her hull is supposed to be under six metres of mud so I’m not expecting a lot, but the dearth of any markers is a shock. Who would have guessed that this government would say one thing and do nothing?

I head away from the creek into the village. A man up a ladder trimming his wisteria is helpful. “The Beagle’s anchor is in someone’s front garden,” he tells me. I follow his directions and spot it: the anchor has become a garden ornament. I head back to the waterfront and ask an elderly couple if the Beagle is behind the fence. “No, it’s supposed to be there,” they tell me, pointing to the saltmarsh just outside the fence. “That fence was for the oyster farm.”

By 1851 the Beagle had become a nuisance, blocking the passage of the oyster boats on the Roach, so was hauled into a mud dock and eventually sold off to a pair of farmers for salvage. The elderly couple point out the location, an undistinguished muddy inlet, with a few shards of old pottery sticking out. There is nothing else to see, but I stand looking for a long time.

In my estimation the Beagle was the most important ship that ever sailed out of Britain: it was the laboratory where modern evolutionary science was started. Inside its cramped quarters, Darwin meticulously constructed the ideas that would humanely destroy a stone age of superstition. It’s wonderful that every Dunkirk vessel, every traction engine and sailing barge gets saved, but those are mere barnacles to Darwin’s leviathan.

I walk back towards the jetty and bump into Mark, another shipwright, revving his motorbike and about to leave. Had I stood watch on the right spot? “That’s it,” he says. “Or that’s what they say.”

I catch the doubt in his voice and ask why. “I grew up here,” he says, “and when I was a kid, the old men would say there used to be a paddle steamer on the same spot. I reckon that might be what the analysis found.”

And the anchor in the garden? “Nah. That’s not the right type for the Beagle. There used to be one that might have been on the Beagle, but it’s now on the quayside in Ipswich.”

He puts on his helmet and straddles the bike. “I reckon she was taken off to be a houseboat.” He roars off down the lane.

I climb up on the sea wall and walk over to where a yacht is sinking into the mud, its superstructure filthy and rotting. The river is in full tidal flood and a fishing boat is disappearing round the bend. One day, perhaps, there will be a replica ship and interactive displays, but for now there is only the sound of the oystercatchers. I like the idea that, somewhere, someone is living on the Beagle, perhaps hanging their hammock where Darwin did for almost five years. Our walk has reached 370 miles and the surprises keep coming.