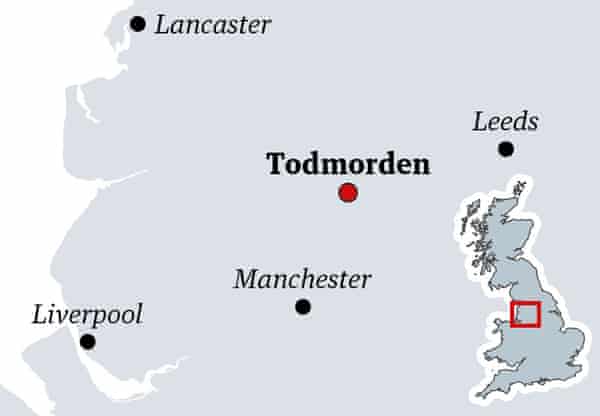

I’m back in Todmorden for my fourth visit in recent years, to rewalk familiar trails and strike out on new ones. Here, the Pennine Way, Pennine Bridleway, Mary Towneley Loop and Calderdale Way are close by, as is England’s highest beach.

“Tod” is a compact town of Victorian sandstone buildings, deep in the Calder valley, with the Rochdale canal running through.

At its centre is the Golden Lion pub (good for Thai food), towards which everything and everyone seems to be forever rolling. The town may lie in the shadow of its better-known neighbour, Hebden Bridge, but which of the two is more eccentric is hard to say.

For more than 10 years, Todmorden residents have pioneered a “sharing, caring revolution”. Incredible Edible Todmorden has dotted the centre and the canal towpaths with beds growing herbs, flowers, fruit and vegetables, maintained by locals and free to whoever wants to pick them. They’ve also embraced kindness as their motto. The word rests on the bank of the towpath by the Golden Lion in large, white block capitals, as if in defiance of all that LA’s Hollywood sign stands for. Tod also boasts one of the UK’s highest numbers of UFO sightings – that there’s a pub meeting for enthusiasts every month may not be unrelated.

Those new to the walking in this area may want to begin by simply following the Rochdale canal. Head north-east out of the town for five miles and you’ll reach Hebden Bridge. Along the towpath is local artwork and plaques exploring the history of beekeeping. There’s plenty of fruit to be picked, too, including golden raspberries if it’s the right season. On your return, pick up the Pennine Way to venture high on to Stoodley Pike. A monument dominates the skyline here, built in commemoration of the defeat of Napoleon. Its 39-step spiral staircase to a balcony offers views over the Pennines.

South-west along the towpath to Walsden lie some of the legacies of Tod’s industrial past: gleaming metal bridges and an imposing 15-metre brick wall that skirts the canal before you cross the main road and everything becomes more verdant, colourful and sleepy. From Walsden, the Pennine Bridleway goes back over the wiry moorland before dropping down to the Shepherd’s Rest Country Inn and the adjacent hamlets of Lumbutts and Mankinholes. From here, join the Calderdale Way and gently wind downhill to Tod’s Unitarian church and, inevitably, the Golden Lion.

New to me on this visit are the beautiful hand-drawn arboreal maps in Christopher Goddard’s guide The West Yorkshire Woods: The Calder Valley. Route 19 begins by the railway station before climbing to Todmorden Edge and across the valley to the Butt Stones and Blackheath Circle. It also takes in half a dozen small, pretty woodlands, including Ewood Wood.

My one concession to motorised transport for the week is a bus to Heptonstall, a pretty cobble-streeted village high above Hebden Bridge, where Sylvia Plath is buried. While Heptonstall has a timeless, sleepy Last of the Summer Wine quality, my walk – No 12 in the OS book South Pennines: Outstanding Circular Walks – is not for the faint-hearted. Skirting a woodland above the deep valley of Hebden Dale, from which the gurgling of a river mixes with birdsong, I cross Popples Common, grassy dales and valleys. Stoodley Pike is often present, punctuating the empty horizon.

After a welcome pint at the New Delight Inn at Blackshaw Head, I descend into the wooded valley of Colden Clough, which would once have shook with the sounds of textile mills; what remains of the buildings and chimneys has long since been reclaimed by the vegetation. It ends with a strenuous climb back to Heptonstall, along a hilltop pathway that requires a head for heights. Here, flat-topped crags overhang the valley far below. The views are spectacular.

On my final day I pack towel and trunks and head to the beach, less than an hour’s walk away. From the Shepherd’s Rest Inn at Lumbutts, a steep 25-minute climb takes me to the top of the moors and to Gaddings Dam, 800 metres above sea level. Roughly 30 square metres, the dam is surrounded by a wall of stone steps that incline towards the water, and has three small sandy beach areas.

Pipits and swifts skim the water to drink and catch insects. People are swimming, picnicking, sunbathing, kayaking and floating in dinghies. I choose a wide rock ledge by the water to sit on. At weekends in warm weather the beach is very popular; it pays to arrive early. Bring food, something comfy to sit on, something to provide shade and waterproof footwear for going in the water; underfoot is a mix of rocks, stones and – as one bather put it – a “whole lot of squidgy”.

I slip into the water and swim to the centre of the dam. Being so high up, isolated and surrounded by empty moorland has a surreal quality to it. My senses, too, are disoriented. Muted conversations carry across the water from every direction, soft and cocooning. “The problem with my legs is that they’re too close together,” a male voice murmurs out of nowhere.

Before I left for Todmorden, a friend gave me a copy of Benjamin Myers’s novel The Gallow’s Pole, based on the true story of an 18th-century coining gang in Calderdale. In my accommodation, I’d also discovered a Gallow’s Pole-themed circular walk covering local places of interest from the story. I’m a sucker for psychogeography, but the week has run away with me. I have had time for neither. But Todmorden and the south Pennines have again enchanted me. They are filed away. Ready for the next visit.