Billionaire Jack Ma has long cast himself as a freewheeling champion of young people and small businesses — the “ants” of China — offering them quick online loans so they can realize the lives they want.

“You’re young; just spend,” said the ads for Huabei, a credit card-like feature on Ma’s financial app Alipay, beckoning a generation of fresh graduates to cities filled with shopping malls.

Shen Xiaoli, 25, bought into Ma’s vision. Huabei funded Shen’s first iPhone. It helped her afford an internship in Beijing. Soon she was using it for a variety items, including taxis and groceries. The bills piled up. Her debt grew: “I felt like I’d never finish paying it back,” Shen said.

When government regulators cracked down on Ma and his fintech empire last fall, Shen decided to cut back and reclaim her former frugal self. She bought only a few items during Ma’s annual online shopping extravaganza. She turned to binge-watching anti-capitalist videos and played the left-wing anthem “The Internationale” on repeat.

“Through baptism in the spirit of communism, I controlled my desire to consume,” Shen said. Last month, she removed Huabei from the “priority pay” setting on her phone app. She plans to soon pay off her last 1,000 renminbi of debt.

“I’ll finally be free,” she said.

A poster advertising consumer-lending platform Huabei of Ant Group at a subway station in Shanghai.

(Getty Images)

Ma is China’s king of disruptive innovation, a leather-jacketed wunderkind as unabashed to push political boundaries as to perform rock concerts for employees. His products — he is also co-founder of tech giant Alibaba — have transformed the nation’s commerce and finance, making him a billionaire and global celebrity.

He has embodied China’s technological prowess for two decades. The scheduled $34-billion stock debut of Ma’s fintech company Ant Group last fall would have been the largest in history. It had been celebrated as a sign of China’s bounce back from the pandemic and entrepreneurial success.

But Ma went too far. His controversial speech in October 2020 at a forum in Shanghai criticized China’s risk-averse financial regulators while many of their top officials sat before him. Such public defiance crossed a red line; regulators suspended the IPO two days before its scheduled date. Chinese leader Xi Jinping himself reportedly ordered the shutdown. Ma vanished from public sight for almost three months.

The message was clear: Big Tech and Big Finance must be reined in. Capitalists should not be given free license in China.

A surprising audience agreed: China’s youth. Many of the “ants” born since the 1990s no longer worship figures such as Ma. Coming of age in a slowing economy under constant pressure to consume, they are suspicious of capitalism and the inequality it spawns. They share reports of tech worker deaths and delivery drivers trapped by algorithms. They use Ma’s products, but are disdainful of his mantras.

A video that went viral after the IPO shutdown explained that Ma’s risky model of packaging and reselling loans is similar to the U.S. home mortgages that caused the 2008 recession. Others featured movie clips of desperate American shoppers, warning that consumerism would make China’s youth “slaves.”

One video host voiced why young people disparaged Ma’s jargon about “struggling” for success. They saw that rewards were often more tied to preexisting privilege than to effort. They found slogans about slavish, fiercely competitive overwork (“wolf culture,” as Huawei’s Ren Zhengfei calls it) insulting.

“When these arrogant ‘life teachers’ say, ‘I’m not interested in money’ and yet are enjoying a very good material life themselves, while making fun of young people nonstop, of course young people are not willing to accept this and will not worship those individuals anymore,” he said.

Meanwhile, analysts tracking China’s fintech sector noted danger in Ant’s practices.

Regulators’ concerns centered on Ant’s microlending services Huabei and Jiebei — Mandarin for “just spend” and “just borrow.” The services connected users with loans, but did not provide most of the credit. That came from partner banks or asset-backed securities — loans it had bundled together to sell as investment products.

A Beijing shopping mall in May 2020.

(Andy Wong / Associated Press)

Ant charged a service fee for each transaction and took a cut of interest payments, while shifting the risk of loan defaults to banks and investors. It funded only 2% of the consumer loans itself in a strategy similar to the subprime mortgage lenders that sparked the U.S. financial crisis in 2008.

Small businesses and individuals in China have a hard time getting credit from large state-owned banks. Ant’s credit products solved that problem. But they also targeted young consumers with little financial experience, quickly qualifying them for unsecured loans.

Eva Wang, 23, was one of them. A daughter of farmers who worked in Chongqing, Wang started using Huabei and Jiebei in 2018. They felt like magic at first. “Huabei and Jiebei are like fake money,” Wang said, comparing them to Q coins, a game currency in the Chinese chatting app QQ. “You just spend it without realizing.”

Last June, Wang lost her job. She had 40,000 renminbi — about $6,100 — in debt and no income for several months. She took out new loans to pay old loans. Soon, debt collectors were calling and texting by the dozens.

“I was afraid to open my eyes when I woke up in the morning. Sometimes my heart beat so fast I felt unable to breathe,” Wang said. Ashamed to face her family, she considered suicide. “That was the first time I felt how painful it is to live.”

Others blame individuals, not Ma’s companies, for irresponsible borrowing.

“Some people use a knife to chop pork ribs; some people use a knife to stab people. The knife has no sin. It’s just been used by different people,” said Lichen He, 27, who works at a research institute in Beijing.

She said Huabei had saved her “countless times” when she had personal emergencies but was weeks away from a paycheck. “Huabei helps me stagger through and survive until the day money comes.”

The 2020 Tmall Global Shopping Festival in Hangzhou, China, on Nov. 11, 2020.

(AFP/Getty Images)

Ant’s microlending has grown remarkably fast. Launched in 2015, Huabei and Jiebei were used by 500 million people in the year before June 30, 2020, according to Ant’s IPO prospectus. A 2019 report by marketing research firm Nielsen found that 86.6% of Chinese consumers ages 18-29 were using credit products.

That is a stark difference from older generations, who were raised with less money, little credit card use and a deeply ingrained cultural propensity to save.

On the popular online Chinese discussion forum Douban, a support group called the “indebted people’s alliance” now has more than 39,000 members. One recent report calculated the average debt owed by people in the group based on their posts: more than $56,000.

In some ways, China is “more liberal than anyone else” when it comes to tech innovation, said Xiaomeng Lu, senior analyst at Eurasia Group. But this has come at a cost as regulators have been slow to intervene, leading to crises such as the boom and bust of peer-to-peer lending platforms that led to mass protests and suicides in recent years.

China’s highly centralized bureaucratic structure can make regulation erratic. Officials hold back, fearful that their actions might hinder Xi’s visions on encouraging innovation and domestic consumption. Few want to risk misreading political intentions. But regulators become more aggressive — as they did after Ma’s Shanghai speech — when they see a clear change in official Communist Party attitude.

“It’s either totally relaxed, or it’s very violent crackdown,” said Angela Zhang, director of the Center for Chinese Law at the University of Hong Kong.

Ant is now going through a restructuring ordered by regulators in December. Its businesses will be placed inside a financial holding company subject to requirements that treat Ant more like a bank than a tech company. Most importantly, online lending platforms such as Huabei and Jiebei will now have to contribute 30% of funding for loans they offer to consumers.

It is a huge demand. In comparison, U.S. regulators required mortgage lenders to retain only 5% of the loans they bundled and sold after the 2008 crisis. But Ant is in no place to resist.

“We appreciate financial regulators’ guidance and help. The rectification is an opportunity for Ant Group to strengthen the foundation for our business to grow,” the company said in a statement issued last year.

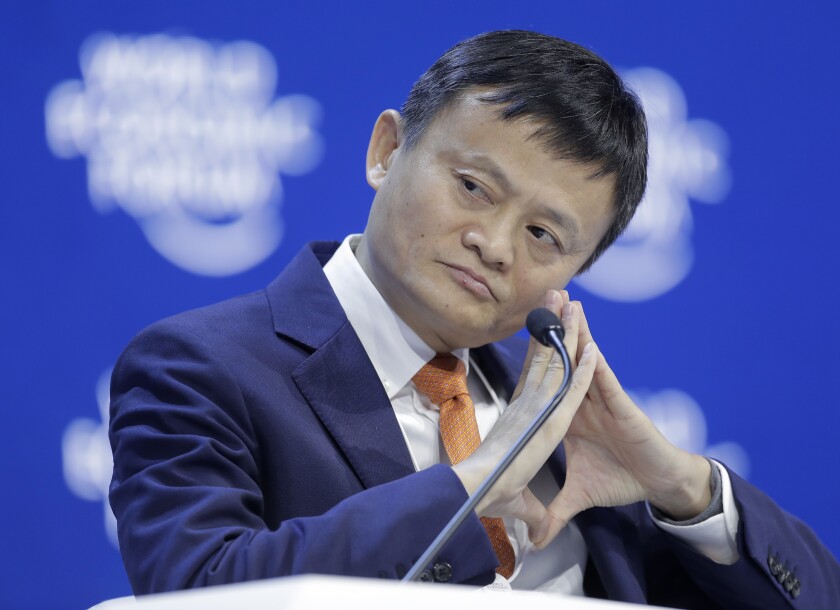

Alibaba founder Jack Ma at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in 2018.

(Markus Schreiber / Associated Press )

Jack Ma reappeared more subdued in late January in a video celebrating rural teachers. Ant will probably have its IPO, but months or even years later, and at a much lower valuation. Microlending will continue as well — it serves the Communist Party’s goals of boosting domestic consumption, especially as the rest of the world reels from the pandemic — but at a slower, more controlled pace. Meanwhile, Alibaba is under investigation for monopolistic practices.

Wang, the young woman who contemplated suicide in Chongqing, now has a job in media paying about $1,100 a month. She told her family about her debt, borrowed cash from friends and has stopped overspending.

“After I stopped shopping, I found out a lot of my consumption was to fill up a kind of emptiness in my heart, not because I needed those things,” she said. She blames herself, not the credit card and online loans, for falling into debt. But she plans to close her Huabei and Jiebei accounts as soon as she pays them off.

“Human greed is very scary,” she said. “Thankfully, I’m young, and it’s not too late to change.”

Ziyu Yang of The Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.