Jane Fraser

wants to simplify

Citigroup Inc.,

the original megabank. That won’t be easy.

On Monday, Ms. Fraser takes over as chief executive of the third-biggest bank in the U.S. Once the industry’s problem child, the bank has stabilized and built up its defenses, proving sturdy and profitable even during the pandemic. Unlike her predecessors, she comes to the job at a time when Citigroup is relatively under the radar.

But Citigroup, which used to be the world’s largest financial-services firm, is struggling to keep up with rivals. While

Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

and Morgan Stanley are hitting new highs in market value, Citigroup’s is half of what it was in 2006. Its profit and revenue, once roughly double that of other big banks, have now been lapped by JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. And last fall, regulators ordered the overhaul of vast systems underpinning its sprawling operations, raising anew questions about the bank’s complexity.

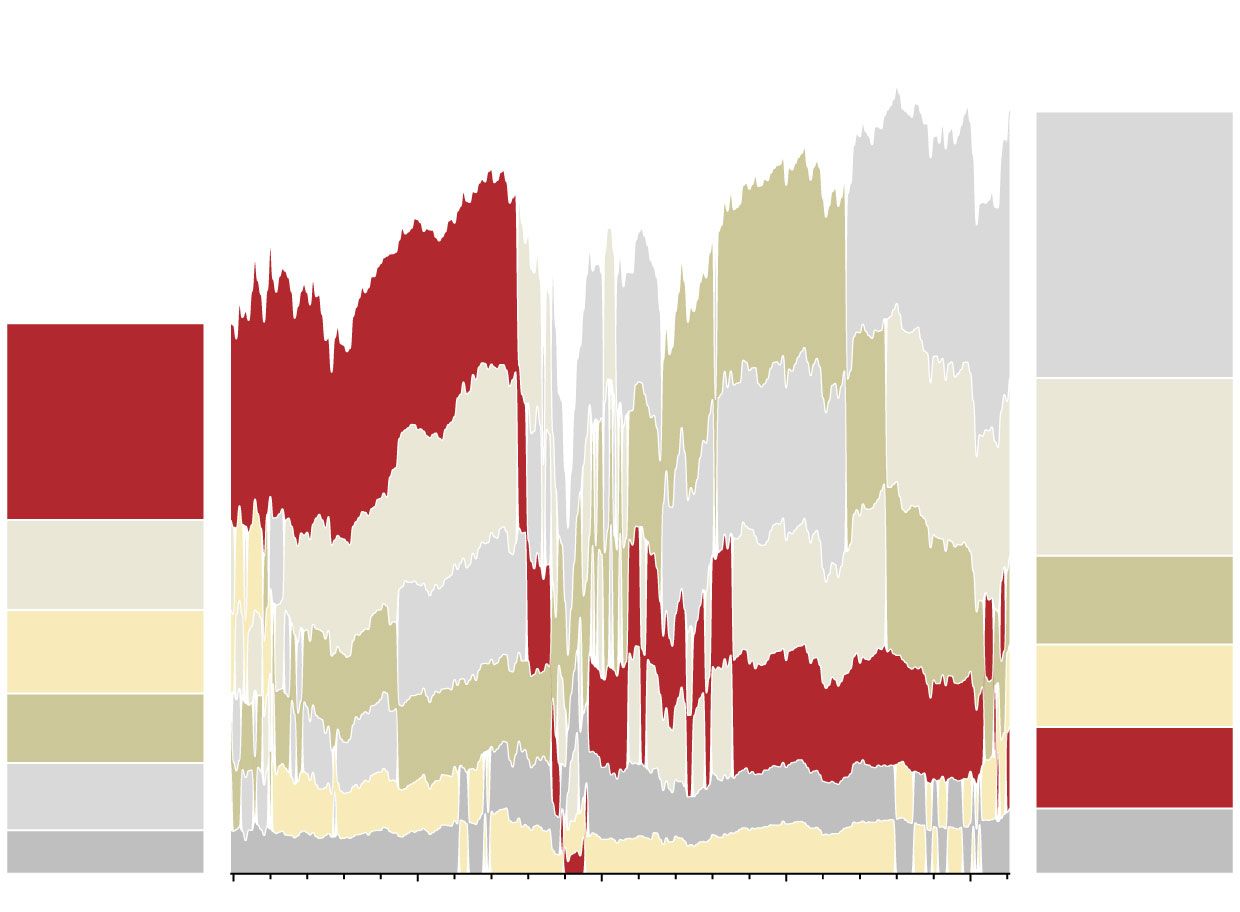

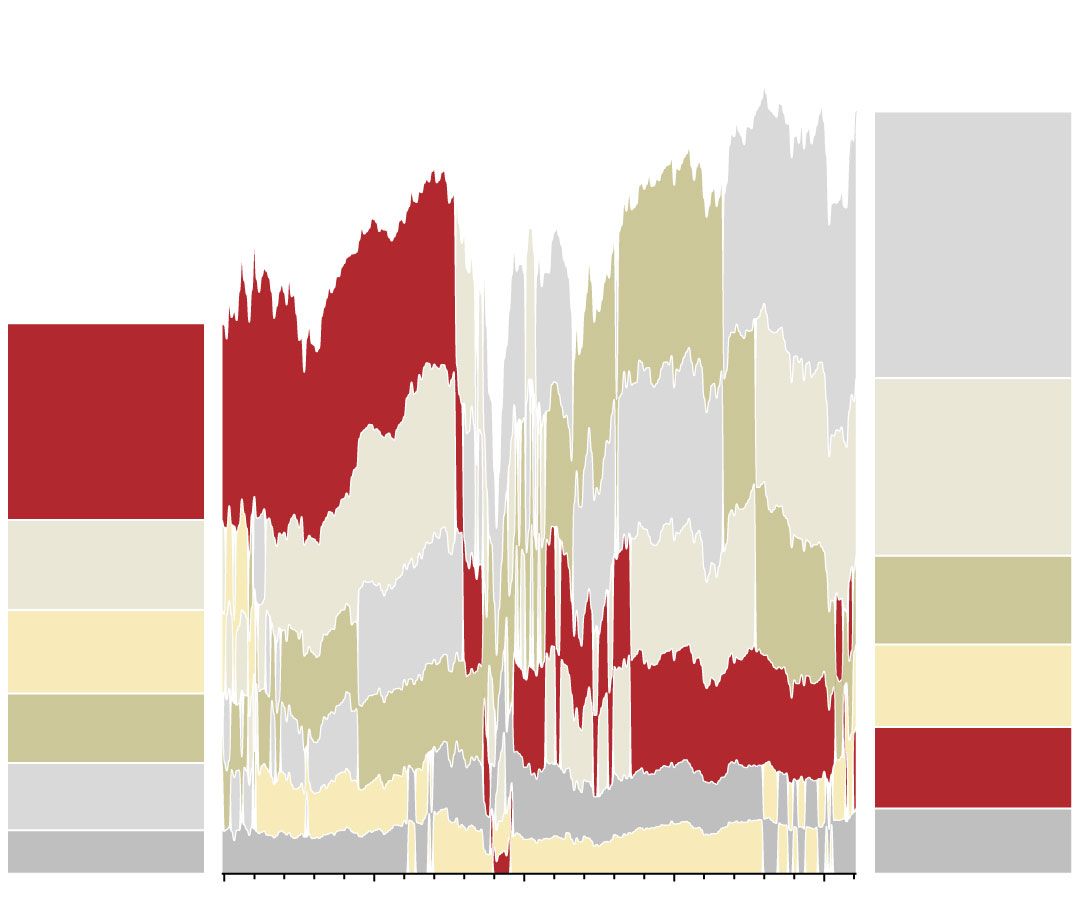

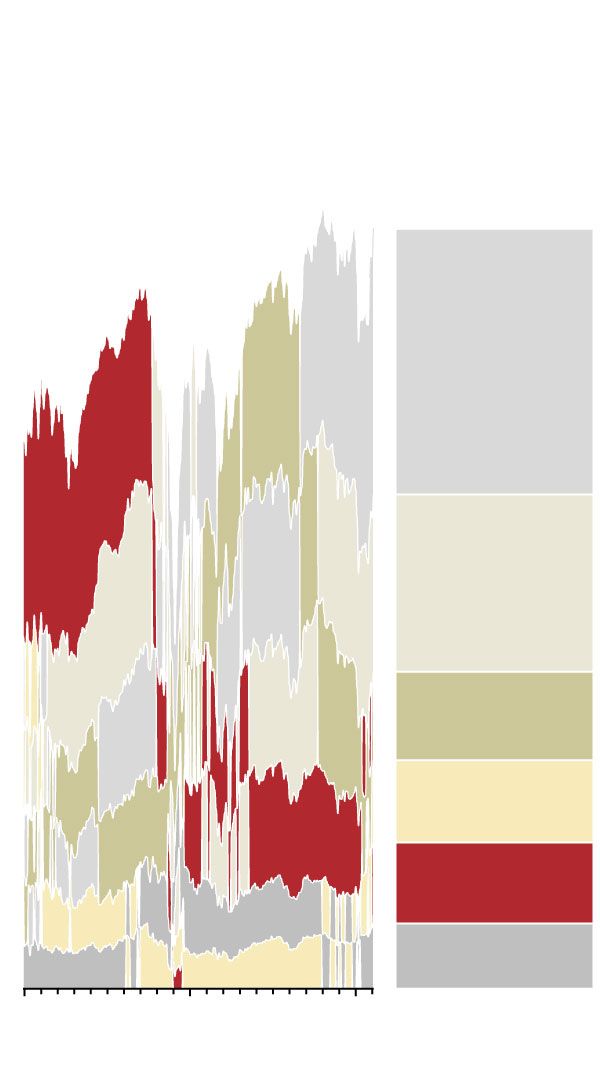

Citigroup was once worth more than twice as much as its closest peers, but has struggled to keep up following the 2008 financial crisis.

Market value of major U.S. banks, monthly

Citigroup was once worth more than twice as much as its closest peers, but has struggled to keep up following the 2008 financial crisis.

Market value of major U.S. banks, monthly

Citigroup was once worth more than twice as much as its closest peers, but has struggled to keep up following the 2008 financial crisis.

Market value of major U.S. banks, monthly

Citigroup was once worth more than twice as much as its closest peers, but has struggled to keep up following the 2008 financial crisis.

Market value of major

U.S. banks, monthly

Ms. Fraser, the first woman to run a major U.S. bank, now has to reinvigorate the $2.3 trillion giant.

She will have to juggle responding to the regulators’ concerns—an expensive, multiyear project—with a reappraisal of the bank’s strategy. Already Ms. Fraser, 53 years old, has launched a “refresh” she hopes can simplify the bank inside and out, making it easier to run and improve.

Simplifying Citigroup is a path similar to what her predecessors,

Michael Corbat

and

Vikram Pandit,

both tried. But Ms. Fraser believes there is more to be done.

“I’m not looking for what’s wrong,” Ms. Fraser said in an interview. “I’m looking for what Citi’s going to be and what is working.”

What Citigroup is today is part of the trouble.

The bank is a giant on Wall Street, in serving multinational corporations and in credit cards. It is second-tier in U.S. consumer banking.

Returns tend to improve with scale in consumer banking, and rivals Bank of America and JPMorgan have supercharged their retail operations with thousands of branches in cities across the country. Citigroup has fewer than 700 branches in just a handful of cities, instead betting on a future of heavily digital banking, including a coming partnership with Google.

Citigroup’s power comes from its global corporate bank. It has operations in 96 countries, helping governments and corporations move money around the world. It is also a leader in raising debt for companies and trading it on Wall Street. But those businesses don’t earn returns as high as they once did, squeezed by crisis-era regulations.

The combination has underperformed rival megabanks, which have kept profits high with a better balance between their Wall Street and Main Street businesses. Analysts and investors have argued Citigroup needs to restructure, with suggestions such as ditching all of its international consumer operations or buying a U.S. bank. Activist investor ValueAct Capital has urged changes to focus on the institutional business.

“There’s little doubt that the two-decade experiment that is Citigroup has failed in every measure,” said

Mike Mayo,

a longtime bank analyst and Citigroup critic.

Ms. Fraser hasn’t telegraphed her plans, but executives said the strategic review will create significant changes. Citigroup recently announced an expansion of wealth-management operations. The bank is likely to shed its consumer operations in parts of Asia, including South Korea and Vietnam, people familiar with the matter said. It doesn’t plan to exit from institutional banking in any countries, according to one of the people.

Chief Financial Officer

Mark Mason

said decisions won’t be based solely on the financial return metrics that have driven the conversation around Citigroup for years.

“I think what our investors are listening for is: Tell us how and why the strategy you’ve come up with makes sense,” Mr. Mason said. “Then tell us what that means in returns.”

Finance chief Mark Mason said Citigroup’s strategic decisions will be based on strengths, not just financial metrics.

But it is unclear if the immediate plans will be enough to appease critics. The regulatory consent order could bar any sizable acquisition for now. And some investors and analysts want Citigroup to shed its Mexico consumer bank or do away with equities trading, which haven’t grown as expected. Neither is likely at this time, according to people familiar with the bank’s plans.

Ms. Fraser said the Mexico consumer bank, which was dragged down by fraud allegations several years ago, has “wonderful scale,” a key barometer for their review. Getting rid of the business would be costly because the unit is tied to a chunk of goodwill on Citigroup’s balance sheet. With equities trading, executives say the benefits for client relationships are too great, even if investors can’t see it.

That may leave investors hoping for a second round of restructuring soon.

The Citigroup of today was created in 1998, a merger of the consumer-focused Citicorp and the highflying Wall Street bankers at Travelers Group. Executives envisioned a one-stop megabank where companies could manage their finances and globe-hopping travelers could always find a Citi ATM.

But Citigroup’s businesses continued operating as silos, and the merger benefits didn’t materialize as hoped. The bank repeatedly ran afoul of regulators. During the financial crisis, it nearly collapsed under the weight of toxic mortgage-backed securities. Since then, it has sold off assets it considered too risky or too ancillary, like a British music empire, a stake in a Mexican airline, a subprime lender and the Smith Barney brokerage.

Ms. Fraser came to Citigroup in 2004 after stints at Goldman Sachs and McKinsey & Co. During the financial crisis, she ran the bank’s strategy division, helping lay the groundwork for the asset sales.

She has hopped around from job to job, running Citigroup’s private bank for the ultrarich, the battered mortgage unit and the scandal-hit Latin America operations. That has given her experience with many parts of the company, though some people say that has made it hard to judge her operational success.

People who have worked with her said she makes decisions quickly, and that she can think strategically over the long term while also running a business. Even when cutting jobs, they said, she wraps her messages in empathy.

She is also known for practical jokes. In January, when Mr. Mason logged into the executive team’s morning Zoom meeting, he found all of his colleagues sitting in front of a 20-year-old picture of him. It was his anniversary at Citigroup. Ms. Fraser kept it as her background all day.

Citigroup announced in September she would be CEO. Regulators were ramping up pressure over the bank’s risk-management systems, and Mr. Corbat decided to step down because he felt that such an expensive, multiyear project was best left in the hands of a successor.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Will Jane Fraser succeed in improving Citigroup? Join the conversation below.

Ms. Fraser said the regulatory issue is her highest priority. The bank delivered on a February deadline to diagnose its risk problems and executives said the relationship with the regulators is productive. She has branded the work a “transformation,” an opportunity for the bank to make changes that are overdue and competitively important.

For instance, regulators had complained the bank lacked clear data about customers. Citigroup had never built a unifying customer identification system across all its businesses. Fixing that would both appease regulators and help bankers deepen their client relationships, executives said.

Ms. Fraser said she knows the work will be a heavy lift but that she doesn’t expect her first day as CEO to feel any different. She is scheduled for a town hall, a meeting with new employees, and some client calls. She is also planning to call some former colleagues and others to say thank you.

Write to David Benoit at david.benoit@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8