‘How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” goes the old joke. “Practise.” Unless you are an elephant, in which case the process is different. In 1934, an elephant stepped on to the stage of Carnegie Hall. Exactly what it did once there is not recorded, but its arrival was celebrated in print, before and afterwards. An article from 6 August 1934 in the New York Times read: “Circus in Carnegie Hall … Elephants, ponies, dogs and other familiar attractions of the tanbark will be seen in Carnegie Hall this season, with the presentation there of a genuine indoor circus.”

The circus, it said, was “offered in cooperation with the United Parents Associations of Greater New York”. Which means that, under the formidable will of the parents of New York, an elephant walked through Manhattan, up Seventh Avenue, and (up the steps? Through the artists’ door at the back?) into one of the world’s most famous concert halls.

The last time I went to Carnegie Hall, a few years back, it had snowed so hard that the pavements had became narrow avenues, banked each side with shovelled heaps that came up to my waist. It had fallen the night before so had not yet turned rat-grey, and everyone was still enchanted by it. The whole theatre, with its red velvet chairs and lavishments of gilt, smelled of drying snow – a sort of illustrious wet-dog scent. People carried newspapers with pictures of the Statue of Liberty, her gown and flame and the fretwork of her crown covered in a dusting of white.

I was in the US because I had written a play, based on the final days in the first world war trenches of the writer Saki (HH Munro), and it had transferred to the tiny Fourth Street Theatre. Some nights were a success: one woman laughed so hard she choked and had to be brought a paper cup of water; another left a little speckling of pee on her seat.

Other nights were very much not – audiences so silent and unimpressed that you could have eaten the atmosphere of icy indifference with a spoon – a bracing kind of experience. It was on that trip that I began the research for my most recent children’s novel, The Good Thieves, which is set in New York in the 1920s. It was then that I read about the circus, and went to see the vast ceiling, over 25 metres high, under which the elephant would once have bowed her head.

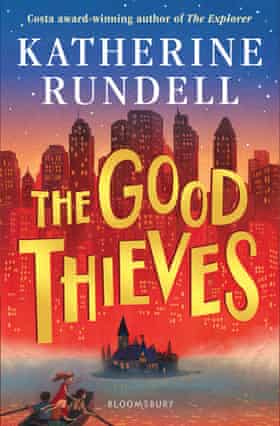

The Good Thieves is a heist: a girl named Vita, faced with a notorious conman who has ruined her grandfather, decides to steal back his rightful property for him. She puts together a crack team of children to help her: a pickpocket, a trapeze artist, an animal-whisperer. The latter two are travelling in the circus that has just arrived, elephants in tow, at Carnegie Hall.

I write slowly – in part because I make so many scratches and mistakes, and in part because I have always loved research. When I am not writing children’s books, I work on the poetry of the English Renaissance at All Souls College in Oxford, and I love the accumulative, building-block, bricks-and-mortar feel of the research process. I have always wanted to write books that are full of wild, improbable-but-just-possible adventures, bolstered by a world of accurate detail; I wanted Vita’s New York to be as real as I could make it, and to be full of the places I love most.

One of those places is the New York Public Library, on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, and I went to work in it during that week of vast snow. The two lions that have flanked the steps up to library since 1911 wore snow hats and snow jackets. They are named Patience and Fortitude; both looked haughty and short-tempered, but stone lions always do: it’s to do with the eyebrows.

The library is one of the most fantastically beautiful in the US: the mural on the ceiling is of a cloudy sky, and chandeliers hang low over desks set with bronze lampshades. I wanted to plan a scene in which the four children break into the library at night, in search of papers stored there in the archive, and are chased by the night porter. I consulted librarians over the exact layout of the building in 1924; I read a book about the tunnels under the city, that were used during prohibition to store illegal moonshine: a possible escape route for my children. (The library, in all its glorious high-windowed loveliness, did make it into the book, but the chase scene did not. I showed my mother a draft. My mother: “So: they need to read some of the library’s papers, and so they break in at night, via the basement?’” Me: “Exactly that.” My mother, infinitely patient: “The thing about libraries, darling, is that if you want to read anything, you just … ask.”)

The children in the book race across Manhattan: from the Plaza Hotel, where the women pitch their voices low and eyebrows high, to the Bowery, where a hundred years ago a man named Dick ran Dick’s Bar and Grill, a speakeasy that served turtle livers (a detail I stole), into the Dakota building (where Lauren Bacall once lived) and past Central Park Zoo. I went, mid-snow. Central Park Zoo remains open even in blizzards, unless they get more than 26 inches in 24 hours. I went to see the seals leaping into white-flecked water, and the snow leopards, which have heated rocks to lie on. The macaques have hot tubs heated to 40C. I worried about the lemurs.

Mostly, though, I kept thinking of the elephants. New York has seen many, in its time. Houdini performed at the Hippodrome in 1918, and each night magically vanished an elephant called Jennie. Nobody knows how he performed the illusion. It was a hard life for her, though he fed her sugar to coax her to cooperate, and boasted that he did not whip her. Jennie outlived him by at least two decades, and would have passed through the streets on parade more than once.

It is a thought to make you shake: the skyscrapers, stretching like the calligraphy of a particularly flamboyant god – and walking beneath them, amid the motorcars and children and stray cats, the elephants. In 1955, the New Yorker published a poem by Rosemary Thomas called The Elephants Pass Carnegie Hall.

There, waiting by the curb for a taxi, we heard,

like rustle of taffeta (but coming towards us)

the uncanny quash-squash, quash-squash of unshod

animal feet, huge, square-toed mastodon feet

shuffling down the street as if it were

the most familiar forest path …

… A ton of elephants, ten tons of elephant

funnelling down West 57th Street

• The Good Thieves (Bloomsbury) is available for £11.30 at the Guardian Bookshop