Five words: Jack Ryan Greener muttered them over and over as he hiked the rocky mess of a trail toward the top of Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous U.S.

Rage on. Stay focused. Believe.

The words shut out everything else.

He didn’t speak to his buddies, didn’t look at the views, didn’t acknowledge anything that would distract him from pounding through the pain. Each step, every jab of his walking poles needed to be precise and deliberate.

Other hikers could slip into autopilot as they struggled to reach the 14,505-foot summit. Greener could not.

He had obsessed about this trail and this peak for 2½ years, ever since an accident left him paralyzed from the neck down, since he left the hospital on a gurney, since he wallowed in dark places, since he taught himself to walk again, since he pulled himself out of his trauma, visualizing over and over stepping onto the top of Whitney.

Pounding the terrain justified all the training, fear, pain, stress and tears.

But he had miscalculated.

Jack Ryan Greener sits for a portrait in the early morning hours at his apartment in Denver. He listened to a meditation app on his phone before getting out of bed.

(Mariah Tauger / Los Angeles Times)

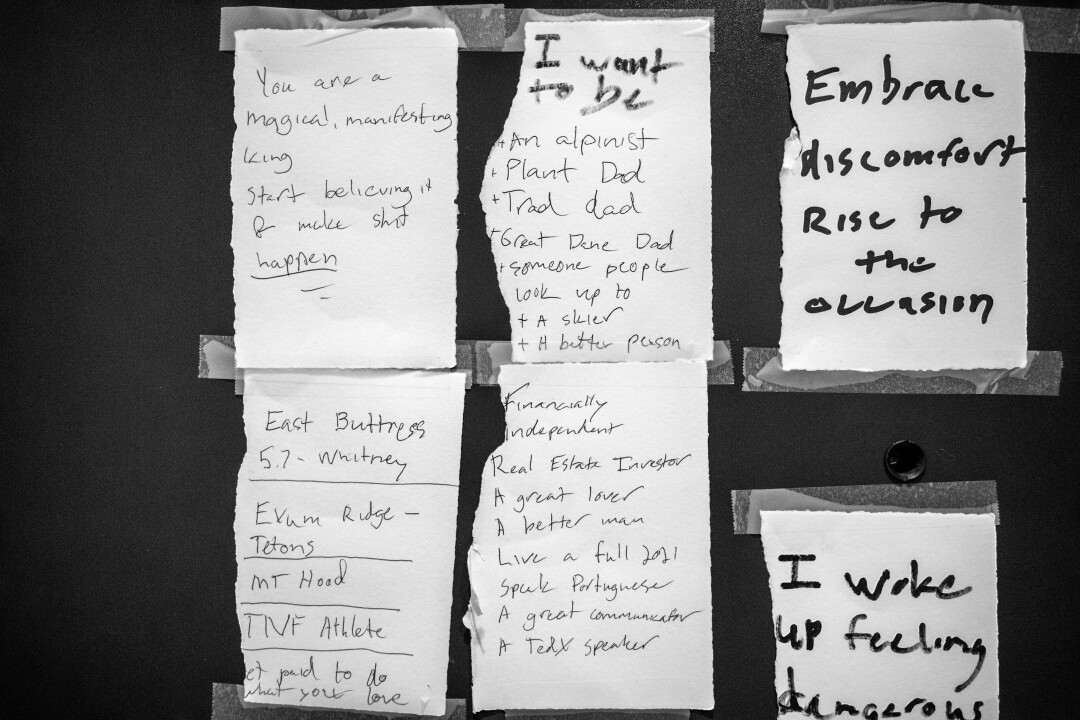

Handwritten affirmations, thoughts and ideas line a door inside Greener’s apartment in Denver.

(Mariah Tauger / Los Angeles Times)

The route was harder than he had expected. Large boulders and rock scree slowed his pace — terrible terrain for someone with limited strength in his arms and legs. The heat was worse than he had expected too, raising fears of dehydration.

The miles felt long, the peak farther away than it should be. Greener was trapped in a hell of his own making. He could do nothing but trudge on, double down on the pain and tweak his mantra:

Rage the f— on. Stay focused. Believe.

‘Old Jack died’

Greener, 26, grew up in San Diego, active, athletic, riding waves, working as a surf instructor in Nicaragua.

“My entire life was devoted to tides and winds and swell charts, and I just knew that I would make this my life,” he wrote on social media after his accident.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

“To be honest, I had never spoken to somebody in a wheelchair, or an amputee, or anyone with a birth defect that resulted in them missing limbs, or a blind person, or a quadriplegic.”

In addition to surfing, he loved Brazilian jujitsu and had a beginner’s white belt. Shortly before he was scheduled to graduate from San Diego State in fall 2018, however, an accident during a jujitsu class left him with a broken neck.

“Old Jack died Nov. 29,” he later wrote.

Greener was rushed to Scripps Memorial Hospital La Jolla, his C3 and C4 vertebrae broken.

Greener’s diagnosis was what doctors call an incomplete spinal cord injury. His spinal cord wasn’t severed, meaning that he had enough brain signals and activity to regain some mobility. How much? It’s frustratingly unpredictable.

“It’s like being in an ice block from the neck down,” Greener said. “You have no idea what is going to thaw. You could get two arms back and maybe some movement in your legs. It’s totally unknown for two, three, seven months.”

Jack Ryan Greener in the hospital on Dec. 1, 2018.

(Jack Ryan Greener)

Dr. Fady Nasrallah, the trauma surgeon who operated on Greener, said the analogy is apt.

“It is hard for me to describe what a patient feels like because we are on the other side of it,” he wrote in an email. “But it is terrifying, as the patient can sometimes feel things that are not happening and then not feel things that he can see happening. It takes a strong will and mindset to live with that and to recover from it.”

Even before he could have surgery to repair his neck, Greener crashed during his first night in the ICU. He sensed something was wrong beyond the spinal cord injury and began screaming, “I’m going to die. I’m going to die.”

Justin Weiner, a nurse who specializes in the neuro, surgical and trauma ICU at Scripps, remembers checking on Greener and calmly assuring him that he wasn’t going to die. Then Greener lost consciousness.

Dr. Giuseppe Ammirati, a neurosurgeon specializing in stroke treatment, rescued Greener, snaking a tube through a blood vessel in his groin and up through his body to remove a 3-inch-long blood clot that had cut off oxygen to his brain.

Patients with clots like this have a 75% to 80% mortality rate, Ammirati said.

But a post-op scan showed that Greener’s brain hadn’t suffered damage.

Next, Nasrallah operated, replacing one of Greener’s damaged vertebrae with a titanium cage and making other repairs.

When the team removed the breathing tube from his throat, Greener could wiggle his big toe.

“I’m going to walk out of here,” he told Weiner.

Nasrallah saw that Greener was young, athletic and tough. Regaining mobility would be an uphill battle, but doable. The doctor introduced him to a lifeguard who had been paralyzed and regained use of his arms and legs.

“You see a recovery, you build hope for your own recovery,” Nasrallah thought.

Watch Jack Ryan Greener tell his story of recovering from a spinal cord injury and his quest to summit Mt. Whitney. (Video by Yadira Flores / Los Angeles Times)

After three weeks, Greener was flown to Colorado to rehabilitate at Craig Hospital, which specializes in spinal injuries.

A year passed. Greener contacted Weiner and other members of the San Diego hospital team. He was back in town, could he take them out for beers? They agreed on a restaurant in Encinitas.

He walked in the door. Stunned silence and then tears greeted him.

Over drinks, Greener revealed his plan to hike Mt. Whitney, a peak he had had his eye on before his accident. He hoped to be the first person to survive such a severe spinal cord injury and reach the summit.

“Dude, name the date, I’m there,” responded Weiner, an ultramarathon runner.

Greener set to work, climbing and hiking in Colorado to prepare. Last year, he hiked to the top of Mt. Bross, which, at 14,178 feet, is good training for Mt. Whitney, both among the 67 “Fourteeners” in the lower 48 states.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

He also documented every aspect of his recovery — from closeups of his scars and videos of his relearning to walk to heart-piercing essays titled “No One Cares About Your Trauma” and “Death and Dating” that he posted on Instagram and his website paralyzedtopeaks.com.

He assembled a team that would include Weiner, who was fast becoming a close friend; Cole Mayer, a friend who worked with Greener and knew him before and after his injury; filmmaker and college friend Chase Viken, who would document the story of Greener’s recovery with filmmaker Alex Romo and videographer Sam Newton. San Diego watch maker Vincero supported Greener’s quest, and, Mammut, a Swiss-based outdoor equipment company, donated gear.

They were the Brotherhood of Jack, a quickly forged troop of young men who didn’t really know what they were getting into, following a guy who thought he did.

The mountain

I’ve summited Mt. Whitney more than 20 times in the last three decades. It’s a hard pull for even the most fit and focused hikers. High elevation robs hikers of oxygen. A person may encounter storms, even snow, in midsummer. Raking winds may make sleeping in a tent impossible.

Some people turn back because of altitude sickness, dehydration, twisted ankles, mental fatigue or all of the above.

Just getting a permit to hike to the top is hard. Inyo National Forest carefully controls how many people are allowed on the mountain — 250 a day from May to October, allocated by lottery. Of the 25,050 people who applied in 2021, 72% were turned down.

The direct route to the top by the Mt. Whitney Trail covers 11 miles each way, with 6,000 feet of altitude gain. Greener had scored the necessary permits in 2020. But fires closed the trail.

In 2021, he didn’t win a permit. Faced with having to again postpone his quest, he made a risky decision. He could obtain permits for a tougher five-day hike that starts south of the peak at a high-elevation point called Horseshoe Meadow, about eight miles west of Lone Pine, Calif., then meets the main trail near the top of Mt. Whitney and continues over the mountain and down the other side.

The longer route would mean hiking more than 37 miles and 8,600 feet of gain. It would require more days on the mountain, more gear, more time for things to go wrong. This would be a trip with heavy backpacks filled with filming equipment and bear canisters to store food, tents, sleeping bags and all the water they could carry.

The team, which affectionately labeled Greener “the general,” let him call the shots. It was his recovery.

They carefully did not let him hear their doubts, worries or fears for his safety.

Friends stay close to Jack Ryan Greener as the sun rises at Mt. Whitney.

(Chase Viken)

Jack Ryan Greener’s foot drags on the terrain as he hikes Mt. Whitney. A barren tree stands against the sky.

(Chase Viken)

The trek

The beginning of the trip only deepened the difficulty. On Aug. 3, when the team first gathered in Ridgecrest, Calif., the temperature had hit 106 degrees and sapped Greener’s strength

The opening day’s hike from Horseshoe Meadow was agony.

“It was all deep sand,” Greener said. “Sand for me is a nightmare.” He dragged his right foot so long that he no longer could use it.

Mayer hung back and shed a few tears at how stoic his friend had become. “I didn’t know who this Jack was,” he said, describing him as a “psycho-focused being, nothing like you’ve ever seen. It’s a thick plate of armor he turns on and off.” But he also saw glimpses of the happy Jack, joking, easy, loving with his friends. Then the armor returned.

That night, the team bedded down in hopes of reaching Crabtree Meadow the next day, but Greener, exhausted, decided to hang back short of the day’s goal.

“My body was so tired, I literally only had one leg to work with for five miles,” he said. He set up camp and spent 15 hours recovering.

Day 3 went better. They reached a tarn half a mile above Guitar Lake at roughly 11,500 feet. They skinny-dipped in the lake. “My anxiety had completely disappeared,” Greener said. “I had 100% confidence in myself.”

They would start their summit bid from there the next day.

On Aug. 7, Greener woke at 1:10 a.m. “Didn’t anyone set an alarm?” the general chastised his troops. “Why aren’t alarms going off?”

At 2 a.m., they started up the trail, headlamps in place. It would take three miles and almost 3,000 feet of gain to top out.

Jack Ryan Greener, second from left, and his friends pause to look at map while hiking Mt. Whitney.

(Chase Viken)

Almost immediately, Weiner began to worry. The trail was too narrow, the drop-offs too close, the rocks too slippery.

This wasn’t the kind of terrain Jack should be on. What would happen if Greener fell?

He said nothing. Instead, Weiner and Mayer took turns spotting Greener, standing within arm’s length in case he slipped. Greener at times walked with a forced, hitched gait on the tough terrain, sometimes held up by his poles, sometimes by his buddies.

Greener wouldn’t be able to carry his own backpack and gear, they realized. Mayer grabbed it, carrying two packs.

“I’m 6 feet 4 and weigh 220 pounds,” he explained, noting that this was his first backpacking trip. Others took turns carrying the load and supporting Greener.

“One of us would be there to tie his shoes or rotate his poles. Everybody was willing to do whatever it took,” Weiner said. “I feel like these guys are brothers for life.”

At 6 a.m., they reached the junction with the main trail. Now they could shed their heavy packs and pare down to light packs for the 1.9 miles to the top.

But the trail became more treacherous, weaving behind rocky precipices that felt endless.

Now, even Greener had become scared. He turned to Weiner and said: “I don’t want to die today. Am I going to die?” Weiner reassured him as he had in the ICU: He wasn’t going to die.

Jack Ryan Greener cries at the top of Mt. Whitney while being comforted by friends.

(Chase Viken)

After reaching the top of Mt. Whitney, Jack Ryan Greener hugs a friend.

(Chase Viken)

As their spirits reached a low point, they realized the peak lay within reach.

Beyond it, they still faced a treacherous five-mile hike back down to Trail Camp, along 99 switchbacks, with water running out and limbs exhausted at the end of what would become a 16-hour day.

For now, though, they could see their goal.

Greener was overcome. A few members of the team went ahead to clear space on the rock-slab summit to film his final steps. They told other hikers what was going on.

Silence embraced the summit as Greener stepped up to the sign that marks the top of Mt. Whitney and tapped his hiking poles. Then cheers. Greener sobbed for 10 to 15 minutes, unable to control the tears. The team joined in.

After the peak

What do you do when you’ve achieved a goal that has centered your life for more than two years? Greener now has two Fourteeners under his belt. He believes he’s the first spinal cord patient to achieve that. (The Forest Service doesn’t track firsts on Mt. Whitney; adaptive athletes with a variety of disabilities have contacted the agency about trying for the high point.)

He has become a fanatical climber who’s earned a spot on the USA Paraclimbing team.

He can’t stop thinking about nexts, like surfing big waves on an adaptive surfboard at Jaws off Maui. He knows he doesn’t have the strength to stand upright and balance, but he can lie down and paddle the board like a kayak. He’s considering a California coastal bike trip, a chance to cycle past the places he surfed when he was Old Jack.

Most recently, he’s thought about climbing Oregon’s Mt. Hood with two friends — one who beat a rare Stage 4 cancer and another who had brain cancer. “We all grew up in the same town and were friends and went separate ways and had tragic events occur,” he wrote.

He bristles at the idea of being an inspirational figure for able-bodied people, something he calls “inspiration porn.” Greener wants to be seen as a bad-ass adventurer first, inspirational second. But he sees his feats — and the documentary slated to be posted on YouTube in October — as a source of assurance and uplift for others confronting physical challenges.

Providing the kind of hope he needed on his path from being paralyzed to gaining mobility — that’s his focus now.

“I just wanted to show kids with a spinal cord injury or cancer or anything,” he said on his way down the mountain. “You can go do these insane things you never thought were possible.”

Photo editing by Times staffers Jacob Moscovitch and Kate Kuo.