The out queer pop star is still a rare thing in our culture, and a fairly new development. In the 1970s, Sylvester, Klaus Nomi and Jobriath were a touch too sophisticated for the mainstream, and Freddie Mercury was as coy about his sexuality as one could be fronting a band called Queen. The fierce queer politics of Bronski Beat and the barely-coded sex-positivity of Frankie Goes To Hollywood made some noise on the US charts in the early 1980s while Elton John still presented as bisexual, but it really wasn’t until Erasure exploded onto the scene a couple years later that an open and defiant gay voice could be heard at your high school dance. Singer Andy Bell has been out, loud and proud from the start of his career, hitting the US top 20 three times during the conservative Reagan and Bush years. He demanded a little respect, on his terms, and he got it.

It’s 34 years since the release of Erasure’s debut album Wonderland, and…well, not much has changed. While the gay audience is more sought-after than ever, openly-gay pop stars are still scarce. Lady Gaga identifies as bi, Sam Smith as gay and non-binary, but beyond them, in the last decade or so, only Lil Nas X has managed to crack the top ten. While the indie world has Shamir, Perfume Genius, and Christine and the Queens, representation for queer kids on mainstream radio is still largely indirect.

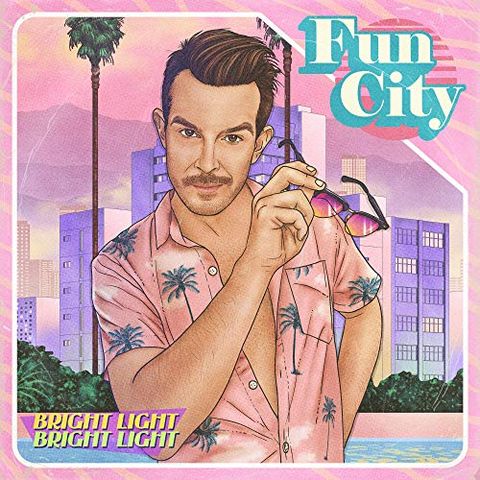

Rod Thomas is here to change that. Recording (mostly inside his own East Village apartment) as Bright Light Bright Light, Thomas has just released his fourth album Fun City, a blissfully heartsick 12-track album packed with collaborations from queer artists, from up and comers like Canadian lesbian pop act Caveboy to established stars like Scissor Sisters’ Jake Shears and Andy Bell himself. Fun City, one of the finest disco albums in a great year for the genre, debuted at #3 on the UK Indie chart, just weeks after Erasure’s eighteenth record The Neon hit #4 on the album chart.

I spoke with the 56-year-old Bell and Thomas, 38, over Zoom in late October. We talked about the queer idols of their youths, the evolution of the gay pop star, the importance of representation and collaboration, and creativity in the year of Covid. Along the way, some dish, some dance, and a solid primer on 20th century gay culture.

Dave: Andy, where are you Zooming in from?

Andy: I’m in London until Tuesday. And then I’m getting a flight to Miami and they’re going to let me in, I hope. But you never, ever know. My civil partner, who lives there, I haven’t seen since February.

Dave and Rod: Oh, my God.

Andy: [laughing] I know.

Rod: A long time. Oh, my God.

Andy: It’s getting to that point now where I’m going to explode. Rod, how’s it going?

Rod: Good. People seem to really like the album, especially the song that we’ve done [“Good At Goodbyes”]. I’ve had lots of messages saying it’s people’s favorite song on the record, so thank you for being part of that.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Dave: The both of you have been out artists from the very beginning. There was never a moment of coming out publicly for either of you. Did you have a blueprint for that?

Rod: Andy, people like you gave me the blueprint, you know? Without you, I don’t think there would be my generation of people being comfortably out in the entertainment industry. So you and people like Jimmy Somerville in the ’80s really made it possible to have those conversations. It’s still evolving and it’s still taking a very long time. When I was a teenager, it still was not okay in Wales to be an out gay man.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: So you can’t remember when I came out, though, can you because you would have been five.

Rod: You’ve always been out with me, Andy.

Dave: Andy, I was a teenager in America, and it made a huge difference.

Andy: For me, there wasn’t really anybody. A couple of TV hosts that were kind of over the top camp, but never, ever mentioned sexuality. We still have them to this very day. My friend calls them “telly nellies.”

There were also drag artists, like one drag artist called Danny La Rue, who was never ever out. He always denied he was gay. Quite a few drag queens of that era said they were tops as well, to make themselves seem less effeminate. That’s all a bit bizarre.

As far as music goes, we had the American artists, we had Sylvester and of course Divine, and gay-identified people like Grace Jones. But in the UK, we had Frankie Goes To Hollywood, which was more hype than it was a gay thing. I mean, I’m not sure in which order was, was it Bronski Beat and then Frankie Goes to Hollywood. I think Frankie might have been first, and then it was Bronski, but I’ll probably be proven wrong.

I just remember going out, and you would have these kind of disco divas, like Earlene Bentley and Miquel Brown doing the old hi-NRG music. To me, that music died out with the clone when the clone died out, with the big mustaches and the leather outfits, the Tom of Finland looking people. Unfortunately that coincided with HIV and AIDS. So it was a really bizarre climate to come out in, you know?

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Also there was a guy called Tom Robinson. I hadn’t really heard of him, but I knew “Glad To Be Gay,” and my uncle had one of his records, “2, 4, 6, 8 Motorway.” He was kind of like folk-punk. I remember reading a poster in London in probably about ’83 or ’84 that he was doing a Gays in Rock seminar in London. So I went there, and I stayed till afterwards, and I said to him, “Oh, how do you come out in pop music?” [Laughs] You know? Because I didn’t know what you did. So he said he wore a pink triangle on his lapel, and when anybody asked him about it, he said, “Oh, you know, that’s the emblem of gay liberation.”

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

I decided from then just to be honest in interviews. I thought [1980s UK chart magazine] Smash Hits were really poppy, but they were the most politically-forwards magazine at that time for teenagers. They did articles with me, and I would just say, “Yeah, I live with my boyfriend.” They took pictures of me wearing a leotard on top of the piano with ruby red slippers and treated it like it was completely normal. Which it is.

Rod: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Andy: I still really admire all of those disco women like Hazell Dean who went around, did these PAs in these clubs, which were really hard work. Probably did about three numbers, with these shitty PA systems, and I don’t know how much they got paid. Thank goodness for Grace Jones, because she always wanted the money before she went on the stage. She knew what those people were like, you know?

Dave: Who were your queer icons, Rod?

Rod: I don’t think I really knew what being queer was until I was in my early teens. In Wales, where I grew up, it was very monoculture, just farmers and coal miners. There was no real discourse about sexuality. There were drag queens that I saw on stage at the Swansea Grand Theater or whatever. There’s a British culture of men in a dress, but it’s not necessarily linked to being gay.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

One of the first things I remember being like a [sound of a head exploding] moment was Erasure’s “Always” video. I’d obviously seen you doing [Erasure’s 1992 ABBA tribute album] Abba-esque, and that should’ve been a clue, right? [Laughs] When I was formulating gay identity, it was stuff like Bjork, Grace Jones, Erasure, Elton John. Not so much Pet Shop Boys, in terms of queer identity. I always just thought they were just two very serious men. It felt like a beautiful ice sculpture. Whereas I always thought that Erasure were so much fun. You just really wanted to be there flying around in the sky with Vince on his little platform with his keyboards.

And then I guess it was probably my affiliation to dance music, because that kind of made me realize that I was not straight. So the Ace of Base adoration, like Black Box, Livin’ Joy, Cappella. I was always very drawn to these powerful dancing women.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: I love Cappella.

Rod: Queer icons were a really weird thing in the UK because like Andy was saying, a lot of the TV personalities that were gay were such stereotypes. They were such a slap-and-tickle, like, “ooh, matron” kind of thing, which you weren’t really able to identify with, nor were they aspirational. A lot of the mainstream representation was very caricatured. So then as an early teen I started to listen to Erasure and Elton John albums, not just the singles. Hearing the songs, like “Sexuality,” the ones that would not be the radio songs, you got to understand who the artists were through the lyrics. And that was what became part of the queer identity blueprint, I think.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: Rod, can I ask you something? I don’t know who your label is. It’s you, isn’t it?

Rod: Yes.

Andy: Yeah, it’s your own label. I was just wondering because, to me, the artwork is very reminiscent of another huge influence for me, which was Casablanca Records and also Carrere, I think they were from France, weren’t they? Carrere Records?

Rod: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Casablanca, even the generic sleeves were so gorgeous, weren’t they? It was so beautiful. With this record, the references that I sent to the illustrator were old ‘70s disco records, like France Jolie and some of those divas, Sylvester, and then like old, ’70s, ’80s horror movies, like Body Double and Dressed To Kill and things like that. And The Eyes of Laura Mars. I wanted it to be like a kind of queer fashion shoot. Attitude Magazine asked me, “Did you have a mood board for the album?” I was like, “Yeah, The Eyes of Laura Mars, Querelle, Sylvester, a horror movie.” That’s what goes on in my mind.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: I love Querelle as well. We used to have gay film nights in London. They were underground, and they would be all nighters. Basically, you’d go there and you’d be trashed dancing in the club, and you could hook up and stuff like that. But they would show Thunder Crack, or Un Chant d’Amour, something from Jean Genet. It was all these different homo-erotic films, which of course, they’re all online now. But at the time, you had to grab references from wherever you could.

It wasn’t just the music, but I suppose music was the most important thing. The reason I mentioned Carrere and Casablanca was, even though it wasn’t explicitly homo artists or anything, it just seemed like the disco beat was the heartbeat to our lives or something. Do you know what I mean? It was almost like that’s what was keeping you alive was that disco heartbeat.

Rod: Yeah. When you listen to the classic queer anthems, they’re very disco influenced. They’re very disco produced. And they do have the traditional disco narrative, which is crying on the dance floor or dancing through pain, which for me is the survival tactic. And it’s what I love about everything from the Sylvester tracks to Bronski Beat to Erasure. “Love to Hate You,” for me, it’s one of my favorites of yours, which has that, “Fuck you. I’m feeling like shit, and that’s my power.” It’s just amazing.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: Oh, gosh, for me, what I love is a phasing, four-on-the-floor drum beat. You know, all the time, that’s what Donna Summer and Georgio Moroder used for “Working the Midnight Shift.” Do you remember that? I can’t remember which album that was from. Was it Once Upon a Time?

Rod: I love Once Upon a Time.

Andy: Yeah. It was Once Upon a Time. It was like a segue to the whole album, wasn’t it, going through? It was almost like a kind of like a mini opera about a knight. And it was just so beautiful.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Rod: I do these DJ parties, and people come and they’ll suggest one of these amazing disco tracks that I loved. It’s just a music genre that I don’t know a single gay person that doesn’t love it. Whatever disco, even the tragic disco albums that were knock-offs. I just fucking love them.

Dave: Especially the tragic ones. For me, Andy, I have to say my freshman year of college, coming out in a very conservative place, the song for me was “Drama.” That was the absolute soundtrack of that year of my life. So thank you.

Andy: Wow. Thank you. You’re welcome. I love it.

Dave: Yeah, and it truly was just one psychological drama after another.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Rod: That’s such a big one for the fans. I’ve opened for Erasure for 27 shows or something. And every night after the show, me and my driver Craig would go out into the house, and we would be somewhere on a balcony and singing every single word of the songs, to the point where people were tweeting about us, like “Oh my God, the opening act is a bigger fan than me.” But when “Drama” came on, at the first “guilty,” the whole room, it’s just like the wig flies off.

Dave: The out pop star is a thing that happened in my lifetime, and previous to that, all of the representation was indirect. It was through divas, or it was coded. Until Erasure, there weren’t out queer people on the charts, singing about their lives in an open and direct way. Did you feel any kind of pushback at the beginning, Andy?

Andy: We always felt like it was one step forward, two steps back. I mean, it was only when we’d had a few hits here in the UK, we started getting deals with Warners and then Elektra. It was almost a test of their power at radio to promote a gay artist. And you felt like they could only take it so far. It seemed like it was gambling, like they only had a few spins of the wheel that they were allowed to do, or something.

It seemed to me like it was almost like a ratio where, as far as you went, as high you could go with your single—which for us, it was like number 12—like that, it was pulled. You’re only allowed to go so far. That’s how it seemed to me, instinctively, and my instinct’s quite right usually.

I felt so privileged that we could tour America, literally play in a church hall in a town. And we’d have people queuing up outside, teenage girls and boys with gay pride badges on, and say, “Hey, gay pride, Andy,” just as we were arriving. So I was just, oh, thanking God…and thanking God that we never had a bomb under the bus. But it was kind of, you felt like you could only go so far. That was the truth. And there are only a certain amount of TV shows that you could be on. I wanted to nail my colors to the wall and be as gay as possible, which I suppose is just like those telly nellies on the TV.

And now, people come out with a bang and a wallop, and it’s all embracing, but it seems to last five minutes. And then if you’re not a million seller, it’s very tough. I’m not complaining, but it’s a really tough environment, being a gay man or woman in the industry, you know? And I have to mention k.d. lang and Melissa Etheridge because they were there as well, at the same time.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Rod: k.d.

Andy: I know.

Rod: Your fucking duet with her. I bought the 12-inch of that recently, and it’s just so good. It’s weird because I think what you did and Jimmy Somerville and other artists in the ‘80s, is you made a space for gay music, as did k.d. lang for lesbian representation. But then I feel like when the industry could get away with making straight artists as gay and camp as you, they forgot a lot of the actual gay artists.

It really wasn’t until Scissor Sisters came along that we were actually allowed to be there again. Before then it was the weird thing of the Fast Food Rockers and Scooch and people like that just being camp, without letting an actual gay person do anything in popular media.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Andy: There seemed to be a crossover period, as you say. During Britpop, maybe mid-’90s or early ’90s, where gay pride became a corporate event, where you had to wear the wristband. And all of a sudden you had straight people on the covers of gay magazines, which was never vice versa. It was never gay people on the covers of straight magazines. And I’m not saying that we should leave them out, it just seemed like we had to make this deal. It was almost like we opened the door to straight people to be accepted, you know?

Dave: To this day, if Channing Tatum says, “hey, I have a gay cousin, and I’m okay with him,” then he’s on the cover of the gay magazine with his shirt off. But working queer artists still have to fight for that recognition. Do you think the gay media supports its own community enough?

Andy: My personal opinion is, since social media, the actual written space in media has become so valuable. And we’ve become so desensitized and so body conscious, it’s so dumbed down that even in gay magazines, now it’s all about selling stuff. It never seemed to be like that before. It was more political, because we were fighting for our rights. Now it just seems to be about selling t-shirts and Absolut vodka.

Plus the attention span is so short. It’s like, who’s next?

Rod: I think there’s a big disconnect in queer culture, but primarily with white gay men. They do want to support a straight female diva more than they have time to support queer artists, especially before they’ve had a hit. When I’ve been playing a Pride festival—and, admittedly, I’ve not had a number one single, I’ve not had a number 100 single, really—but if I’m on the bill, I’ve heard people be like, “Oh, nobody knows who that is.” They want Miley Cyrus or Ariana Grande or whatever. If I had had a hit, it would be a different story. But can you not have equal space in your life for a straight diva and a queer artist? Because if you don’t support your community, then none of us are ever going to get anywhere.

There just doesn’t seem to be that eagerness to adopt your new favorite queer artists as there is to adopt your new favorite diva. It’s a difficult thing because I love listening to female artists. I spend most of my life listening to Mariah Carey. But I do try and look out for new queer artists and support people and spread them around.

Something I do like about social media and the way things are these days is it’s easier to connect with other queer artists. Like with Fun City, there’s 12 queer artists on it. Everybody from Andy to a complete newcomer. And I wouldn’t have been able to do that previous to this social media world. It is easier for people to seek out artists if they want to. I don’t know if the desire to do that is still there because there’s such a saturation of content and like 3000 new singles every week on Spotify. Even though it’s easier to put yourself out there, it’s a little bit harder to get people to actively seek you out. And as we know, people are lazy as fuck and can’t be bothered.

Andy: To be honest, as well, I don’t know who’s gay anymore. I don’t. Because there’s so many people. But that’s what we’ve been fighting for the whole time. You become visible to be invisible.

Rod: What is interesting about being in my position or my generation with queer identity in music is that you do get to shape the road. I’m trying my best to get my pitchfork out and forge a little path. And what I’m hoping I encourage people to do with this album is to talk to each other and to work with other people and to emphasize a sense of community, which I never had growing up. I couldn’t name 10 gay artists growing up that I thought I could be friends with, or go on tour with. And I always felt very isolated. I was this lone satellite, just kind of orbiting a world that I didn’t really ever get allowed into.

We have to emphasize community and the fact that working together makes everything a little bit stronger and a little bit more visible. I’m hoping that with this record, which is all collaborations, emphasizes how much better you are together versus alone and might inspire a few people to do the same kind of thing. And that it doesn’t have to be with somebody famous. Like Andy and Jake Shears are incredibly famous, and then you have Illustrious Blacks or Caveboy who are on the rise. That was pointedly done to counteract the fact that people only really care when people are famous.

Andy: Rod, do you do it by being a fan of their music or is it just random leads?

Rod: Some of them were friends before I got to know their music. And then with Caveboy, for example, my friend worked at Amazon Music, and she said, “You should listen to this album.” And I thought it was fantastic, so I just sent them an email, we ended up talking back and forth because we had loads in common, and in two weeks I had their vocals on the record.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

All of the people on the record are really warm, genuine people who care about the world outside of themselves. And so I would like to use this path that I’m making or forging or breaking or whatever, to remind people that you can do that and have a lot more fun with music, especially as a queer artist. Just allow other people to come on board with you.

Andy: That’s really sweet. You should get an alter ego, call yourself the Vocal Snatcher.

Dave: Finally, I am just noticing, are we all wearing statement T-shirts?

Andy: I’ve got my Madonna World Pride T-shirt, although it’s a bit smelly. It was on the floor and I thought it was worth one more wear.

Rod: Dave, you have your Biden/Harris shirt.

Dave: I do indeed have my Biden/Harris shirt.

Andy: You got your Biden? Yay!

Rod: I have my Joan Cusack from Addams Family Values sweatshirt on. “I want you dead, and I want your money.”

Andy, congratulations on The Neon, by the way. Top five is fucking amazing in this day and age in the UK. It’s so incredible. I’m so proud.

Andy: Thank you very much. Thank you. It’s all over in an instant, so enjoy it while you can.

Bright Light Bright Light’s Fun City and Erasure’s The Neon are available now. Rod Thomas DJs the occasional “Romy & Michelle’s Tea Dance,” which you can watch on Twitch; he broadcasts as @brightlightx2. Andy Bell remains in London.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io