When editor Kirk Baxter boarded labyrinthine, Old Hollywood drama Mank, he was met with multiple timelines, and rapid-fire dialogue from a vast assortment of real-life characters.

While Baxter would be tasked with guiding the viewer through the complex period piece, he never thought of the film as a challenge, per se. “I look back,” he tells Deadline, “and see it as a joy.”

Directed by David Fincher, Mank follows alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), as he endeavors to finish the screenplay for Citizen Kane. Along the way, it also examines the washed-up wordsmith’s relationships with icons of his time, including Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), and Orson Welles (Tom Burke).

Related Story

Sound Designer Ren Klyce Breaks Down The Elaborate, Multistep Process Of Crafting Monaural Palette For David Fincher’s ‘Mank’

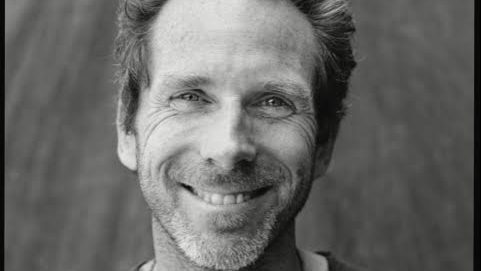

First collaborating with Fincher on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008), Baxter quickly developed a shorthand with the auteur, going on to reteam with him on four other films and two TV series. While Benjamin Button would land him his first Oscar nomination, his first pair of statuettes would come shortly thereafter, for his contributions to The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Poised to return to the race once more with Mank, Baxter spoke with Deadline about the scene in Fincher’s longtime passion project that scared him the most, the performance that captured his heart, and the aspect of the process that felt like “the cherry on top.”

DEADLINE: What were your first impressions when you read the script for Mank?

KIRK BAXTER: Well, there’s a reasonably amusing story with the first read because David spent about 30 minutes in his office pitching an upcoming movie to me—a movie that he wants to make that has a lot more bloodshed—and I was unbelievably excited about it. Then, a week or so later, this script is sent, and me being me, I don’t remember the title of the one that he pitched to me. I hopped on a plane, pulled out what I thought was going to be this wonderful tale of an assassin, and then got completely confused for the first 30 pages, going, “These people seem kind of physically harmless.” [Laughs]

So, my first read was not all that affected because most of it was almost speed-reading, going, “This makes no sense to me.” But by halfway through the script, I got embraced with what it was, and was excited by it. I didn’t go back and reread it until just before we started, because I wanted to get another fresh page. I read it from the beginning again, and then I keep the script away, and just deal with the footage as it comes in.

DEADLINE: Did you have in-depth discussions with Fincher, heading into the shoot?

BAXTER: No. Because we know each other well, I take pride in my role, in trying to remove weight from David’s shoulders, because there’s a long list of people tapping him on the shoulder. I’ve always seen my role as reactionary to what he’s shooting. I work within those confines, and our dialogue is based on scenes that I’m sending him, as I execute.

There was one discussion of whether we should deliberately make the editing clunkier, so that it would more replicate a 1930s movie, and my response was, “F—k that.”

DEADLINE: I’d imagine that you were one of the only department heads whose work didn’t involve emulating period style.

BAXTER: I didn’t think the editing was required to do that. To really strictly stick to the format of the ’30s, we’d be sitting in two-shots and fifty-fifties and wide shots for much longer periods of exchange, and that’s how a lot of those things [would play out in] a stage play. David has a lot more coverage, and with that, you’ve got the ability to dissect scenes, and control and manipulate a lot more, due to editing and movement. And I don’t think that breaks the spell. I do believe you can get transported into a film of that era by how it looks and sounds, and no one’s writing a review saying, “Damn, the fast editing really screwed the pooch.” I think you accept film language today to come at you with a more rapid pace.

DEADLINE: When did you officially start your work on Mank? Can you recall the first scene you cut?

BAXTER: I typically start on day two or day three, really early in the process, and I edit as fast as I can, and try to keep up with camera as best I can. So, I’m there as a fail-safe. If he’s worried about any particular scene or performance, he can direct my attention to something, and then I’ll build that out and get it back to him.

I do recall that, in general, some of the earliest stuff that he shot was more of the effervescent, bubbly Hollywood scenes—the writers’ pitch in [David O.] Selznick’s office, that type of material. It was quite comedic and finishing in end gags. There’s a few of those that came in, in a row, and it did make me sort of go, “What?” Then, when the bungalow scenes began to come in, that’s the heart and soul of the film, and the grounding of the movie.

DEADLINE: How did you grapple with the film’s structural complexity? Were the screenplay transitions appearing in it key in guiding viewers through the story?

BAXTER: Yeah. The titles being typed on really grounded everything. It was David’s idea to type them on, and to bring that sound effect to it, and I think the repetition of that always [tells you], “We’re going back in time. This is a memory.” We tried to be quite consistent, in regards to how we would end scenes in the present, and the speed of what we would fade down, and the amount of time it would be in black, and how we would then come into scenes of the past. We sort of had a map that we tried to stick to, so that the audience didn’t get lost in whether something was past or present. But it was intended to bounce around.

DEADLINE: The performances in the film are superb, across the board. What were they like to work with?

BAXTER: Gary was exceptional. I think they all were. For Gary, especially in the final act, playing someone drunk can be a challenge, for things to be legible. And take after take, Gary really did a terrific job. That could have been much more of an uphill climb for me, if he didn’t bring it. But the performance that captured my heart, without playing favorites, was Lily Collins, playing the secretary in the bungalow.

From the first moment that she came on—and it’s not to take away from anyone else in the movie—I just found her to be so exacting, and I didn’t know her beforehand. I wasn’t aware of anything she’d done, and she played quite a strict and brittle role, but had this incredible warmth, and delivered every line with such precision and grace. [Her performance] was a real pleasure to put together.

DEADLINE: What went into shaping the film’s montages, including the nightmarish one on the night of the 1934 California gubernatorial election?

BAXTER: The montages—there are two of them—escalating inner dialogue inside Mank’s drunken head, they were shot over multiple days, weeks apart sometimes. So, I found myself cutting those montages as if nothing more was coming. Often, I’m not dealing with what the schedule is, and not looking to see if more footage is coming.

The music for the second montage came in pretty early on from Trent [Reznor] and Atticus [Ross], and it was absolutely perfect for the scene, so I was able to craft it quite precisely. Then, a week later, I would get more shots, and I would have to do it all over again, and squeeze all these shots in, and pull apart something that I was already happy with. [Laughs] But it improved because now, it’s got more depth. Then, another week later, another five shots would turn up, so it was something I just kept redoing. But it was a pleasure to keep redoing it.

When it became not just a scene that sat by itself, but a movement of the entire election night, then we kind of gave it another crunch. Without dropping shots, I took about a third of the time out of the montage scenes, and really picked up the pace, so that they were weighted in the way they deserved. I think it became clearer, when they became more dense and concise, what they were, and when we wallowed around in it for too long, the importance of it was too big.

And you know, that’s editing. You craft things to live in a single world, as if it’s the only thing that exists, and then you’ve got to make it fit within the bigger picture of the movie.

DEADLINE: I know you were nervous about cutting the scene in which Mank delivers his drunken Don Quixote speech at Heart’s San Simeon estate. What most concerned you there?

BAXTER: There’s always a bit of apprehension when you’ve got the larger scenes to put together, whilst you’re assembling the film and trying to keep up with camera, because if it’s a five-day shoot for one scene—if it’s a really big, dense scene—that’s going to take me more than a week to take care of, and you end up getting further and further behind. So, there is this thing of going, “Oh my god, there’s an avalanche coming. How am I going to survive?” But it was shot towards the end of the film, so I didn’t have the pressures of needing to strike a set, or release actors, and that sort of thing. The movie was doing what it was going to do at that point, so I had the time to put it together.

Surprisingly, or not surprisingly, my fees weren’t warranted because of Gary’s performance. He did an exceptional job. The volume of material—based on how long the scene is, and how many people are in that room, and how many actors Gary’s interfacing with—brings a lot of footage. But the blocking of the scene, of Mank walking around the table, kind of dictates eyelines, and where you need to be at what time. So, a lot of it can get sorted out, once you work out the rhythm of how you want to put it together, and I found it to be a joy and a pleasure to do. So, something that I was quite nervous about actually ended up just being a thrill.

DEADLINE: What were the highlights of your time on Mank?

BAXTER: I enjoyed all of it, but the cherry on top is always the music. Trent and Atticus, their approach is to hit us with 20 tracks that haven’t been written to picture—that have been written for the movie, not to the movie—and you get the freedom to place things in the beginning, working out which one became the opening title music, and which became Mank’s theme, and how we would evolve that. That’s a process that a lot of people are involved in, but that’s the part that I guess has just so much pleasure.