If the Newfoundland and Labrador provincial election is any indication, holding a federal election during the pandemic could prove tricky, according to political scientist Kelly Blidook.

“It’s an election that … started out with some questions and became, if you will, a bit of a disaster,” said the associate professor at Memorial University in St. John’s.

When Premier Andrew Furey announced in January that an election would be held on Feb. 13, the province had only five active cases of COVID-19.

While cases remained low in the weeks before election day, with five days to go, COVID-19 surged in the province, with variants blamed for the rapid rise.

On the eve of the election, the province’s chief electoral officer, Bruce Chaulk, announced that in-person voting would be suspended. Those who had yet to cast their vote would have to do so by mail-in ballot.

Two-and-a-half months after the election was called and following weeks of counting, the election results were released all at once on Saturday, with Furey, the Liberal leader and incumbent premier, winning a slim majority.

But with turnout below 50 per cent and concerns over the vote’s legitimacy, questions about the province’s handling of a pandemic election remain — standing as a warning for a potential federal election, Blidook said.

“The big problem here is that it appears there wasn’t really a lot of planning in case COVID became worse,” he said.

Elections Canada says it’s prepared

The federal government isn’t due for an election until October 2023. However, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s minority Liberal government will face a major test in the House of Commons on April 19, when the federal budget — the first in two years — is released.

Along with Newfoundland and Labrador, provincial elections have been held in British Columbia and New Brunswick during the pandemic. Two federal byelections have also taken place, but an election on a national scale has yet to be tested in the face of COVID-19.

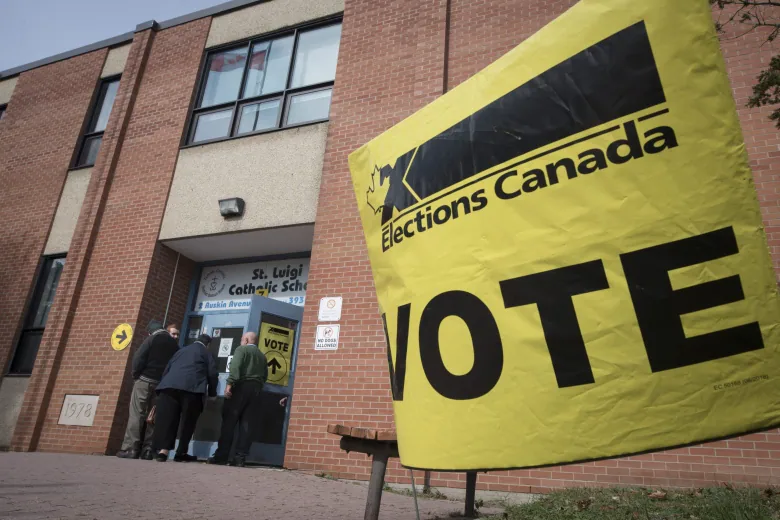

For its part, Elections Canada says it is prepared to safely run a general election during the pandemic — with both in-person and mail-in voting as required by the Elections Act, if an election is called.

“Part of our core function is to be able to go whenever an election is called because we can’t always rely on the fixed election date — and that’s especially true during a minority government, as we’ve been in since 2019,” said Elections Canada spokesperson Natasha Gauthier.

Chief Electoral Officer Stéphane Perrault expects Elections Canada will receive up to five million mail-in ballots in the next election, up from 55,000 in 2019, according to Gauthier.

Mail-in voting, alongside advance voting ahead of election day, are on the rise, said Peter Loewen, a professor at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. In British Columbia, which held a provincial election last October, more than a million of the province’s 3.5 million eligible voters cast their ballot using these methods.

And given the significant number of polling stations open on the day of a federal election, Loewen agrees that in-person voting can be done safely.

“In most Canadian elections, you can be in and out of a polling place in less than 10 minutes,” said Loewen, who has researched voters’ opinions on voting safety for Elections Canada.

Concerns over election integrity

Blidook acknowledges that the federal Elections Act provides greater flexibility, including a provision for mail-in voting, which could benefit Elections Canada during a pandemic.

As COVID-19 affects parts of the country differently, though, he said that varying provincial restrictions could make administering an election on a national scale difficult.

“You could actually be working with a patchwork of regulations where some citizens are being afforded completely different opportunities to vote than others are,” Blidook said.

WATCH | Liberals win majority in Newfoundland and Labrador election:

The Liberal Party will form the next government of Newfoundland and Labrador, garnering 22 of 40 seats in the provincial election. The results, released after weeks of ballot counting, mean incumbent Premier Andrew Furey will continue to lead the province. 3:34

Gauthier said Elections Canada is working with local authorities to address concerns over regional public health measures, but she acknowledges that there are challenges in some ridings. For example, more than 100 ridings fall under the jurisdiction of multiple public health units.

“So even in the same riding, you might have different rules in place in different parts of that riding,” she said.

Safety isn’t the only concern about voting during a pandemic, said Blidook, who cautions that in Newfoundland and Labrador, trust in electoral integrity is down — in part because of the changes associated with holding an election during the pandemic.

That distrust stems from confusion over the validity of running an election primarily based on mail-in ballots — something Blidook said the province’s Elections Act is unclear on — as well as concerns that a handful of voters were able to vote by phone, which is illegal in the province.

“We have reason to think that this election wasn’t done properly. Any time that you do that, you diminish, to some extent, trust in democracy more broadly,” he said.

Risky decision

Loewen said that given the slow rollout of COVID-19 vaccines and the challenge of defending a government or party’s record in the midst of the pandemic, he doesn’t expect there to be a federal election any time soon.

“I don’t think any time is going to be great for the government, but I think that now is not the time for them to go to an election now,” he said.

Ultimately, if an election is called, however, Loewen said he’s confident that it could be done safely.

But as the Newfoundland and Labrador example shows, there are risks to that decision, Blidook said.

“For me personally, I would think that you wouldn’t really want to take those kinds of risks sooner than the fall,” he said.

“I think that there’s a number of them, and I think Newfoundland and Labrador is one of those cautionary tales to say this can go wrong.”

Written by Jason Vermes with files from CBC News. Produced by Menaka Raman-Wilms.