One morning in June, I stood looking at El Capitan’s so-called Dawn Wall, mist coming off the meadow around me. This wall, a particularly sheer surface, was climbed for the first time in 2015 by Kevin Jorgeson and Tommy Caldwell, a man who didn’t let the loss of half his index finger to a power-saw sideline him. As I looked upward, I thought of Caldwell’s refusal to finish the climb on his own, descending to coach and cheer Jorgeson through a difficult stretch.

I walked past the long vertical ridge bisecting the face of El Cap, which, for obvious reasons, is called the nose. I looked up to the part Alex Honnold had free-climbed in 2017. “I’ll never do anything to equal that climb — and I’m OK with that,” said Honnold, the focus of the Oscar-winning documentary “Free Solo.”

Yosemite has captivated generations of climbers — and those who worship them. Now a small museum in Mariposa, Calif., not far from the park’s granite walls tells part of the story. Ken Yager, 62, founder and a veteran climber with more than 300 first ascents to his name, devoted decades and $250,000 to assembling artifacts and photos that would provide a window on this niche world.

Photographs and gear on display at the Yosemite Climbing Museum.

(Dean Fidelman/Yosemite Climbing Museum)

Yosemite climbers in the 1950s and ‘60s were a breed apart. Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard; the late David Brower, one-time Sierra Club executive director; and Royal Robbins, who founded his own outdoor brand, are among the more well-known names.

Yager gets the climbing story right, weaving together the tech, the business and the human-interest aspect displayed in three rooms at the museum. “It has everything you would hope in it, and more,” said Joseph Taylor, author of the 2010 book “Pilgrims of the Vertical,” a history of climbing in Yosemite. “I don’t know quite how he got it all, but it’s all there.”

Old hand-made pitons used by Half Dome climbers in the middle of the 20th century.

(Dean Fidelman/Yosemite Climbing Museum)

The artifacts show innovations that have helped climbers succeed up ascents once thought impossible. Here are the pitons forged from steel by a climbing blacksmith who developed them to work in Yosemite’s distinctive long vertical cracks. There are the early hemp ropes, and then more high-tech ones, so much lighter and stronger. Leaning against a plexiglass case is the jumar, the clamp that attaches to a fixed rope, worn by Mark Wellman, the first paraplegic climber to make it up El Cap in 1989.

The climbers who founded the big gear and clothing businesses are featured in the photos on the walls. One shows Patagonia founder Chouinard climbing, paired with a display of equipment he hand-forged in the 1960s.

The museum also focuses on the outsized personalities who have pitted themselves against the valley’s high walls. Yager and his fellow docents, mainly also climbers, have the stories to help make the photos come alive.

On a recent visit, Yager pointed to a photo of a hairy man with bloodshot eyes who glares from one wall. “That’s Warren Harding [the climber, not the former president], the first man to make it up El Cap,” he said. Harding and his team used extensive aids to do so, Yager said. It took 45 days over two years, with climbers eating a Thanksgiving dinner in a bivouac on the wall. “He was also,” Yager added, “the first hitchhiker I ever picked up. Looking at him, I can’t believe I did that. He looks like he’d just as soon murder you. He taught me to drink — not wise to try and keep up with him.”

Rope used by climber John Salathé.

(Dean Fidelman/Yosemite Climbing Museum)

Harding’s great rival, the relatively clean-cut Robbins, appears on another wall. Robbins and his team were the first to ascend the northwest face of Yosemite’s other great peak, Half Dome. Robbins, I learned from Yager, believed how you got up to the top was as important as whether you did. In a fit of pique, he retraced Harding’s route up El Cap, pulling out the bolts and pitons that Harding had used — “aid climbing” they now call what Harding did — not free climbing, where you use your ropes to stop you from falling, not to help you rise.

Classic climbing boots are on display at the Yosemite Climbing Museum.

(Dean Fidelman/Yosemite Climbing Museum)

Yager knew many of the climbers featured in the museum. He spoke at Harding’s funeral and called the late Robbins every year on his birthday. He pointed at an Ansel Adams picture of the blacksmith climber John Salathé, atop a tall massive pillar of rock in 1947, belaying down a climbing partner.

“When he died [in 1992],” Yager said, “there was no recognition of Salathé’s contribution. I asked a friend to write an obituary, and started to ask people of his generation for the stuff in their garages. I promised them I’d do something with it, and, at last, we’ve kept the promise.”

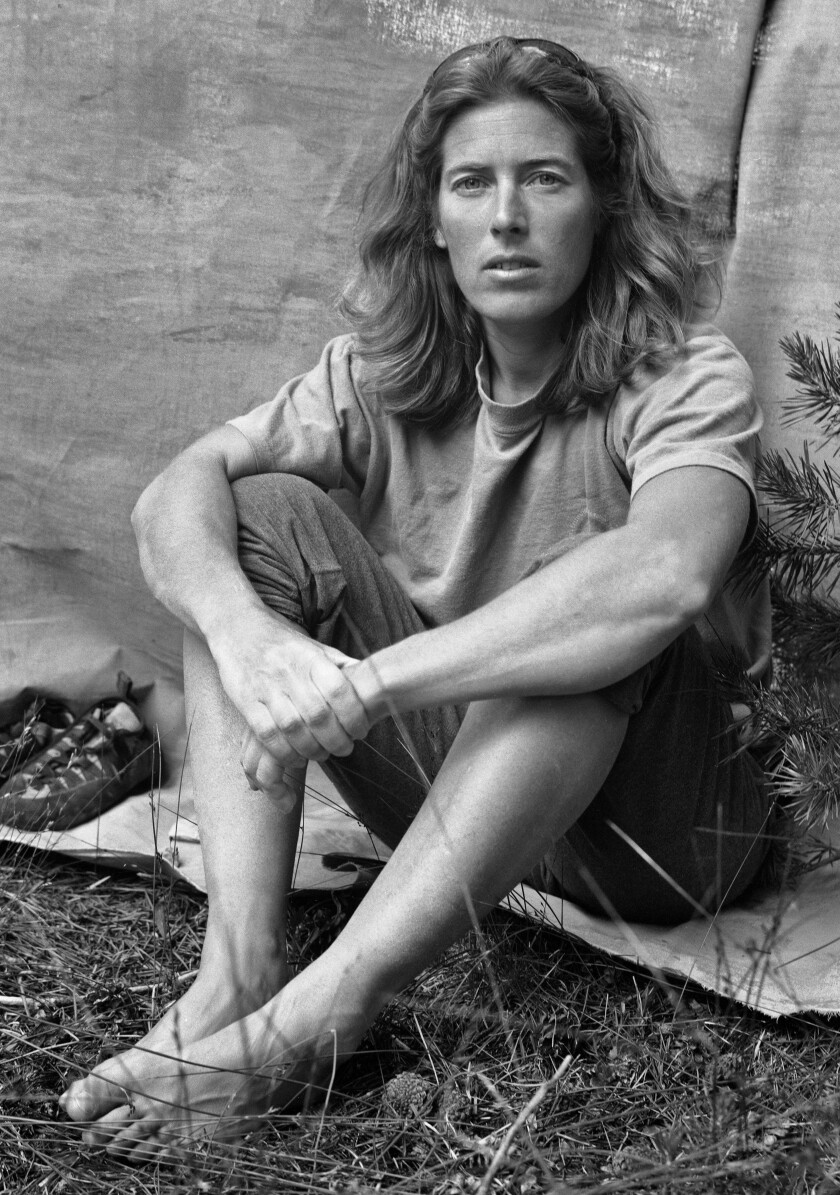

Most of the climbing legends on these walls are men, but one wall is dominated by a photo of Lynn Hill, stretched out on El Cap. She became, in 1993, the first person to free climb the nose of El Cap, famously saying, when she reached the top, “It goes, boys.” Reached by phone at her home in Boulder, Colo., she recently said, “People love it, the sass in it.”

Climber Lynn Hill.

(Dean Fidelman)

Considered the world’s best climber in her day, Hill was among the first to be treated as a star in mainstream culture. She appeared on the “Tonight Show With David Letterman,” even demonstrating a climbing move in the studio. “To be honest, I think he was a little intimidated by me,” she said.

The museum’s story pretty much ends with Hill. It sticks to climbing from the 1950s to the 1990s, a prelude to the extraordinary ascents that followed.

If you go

The Yosemite Climbing Museum is located in Mariposa, Calif., right near Yosemite National Park.

(Dean Fidelman/Yosemite Climbing Museum)

Yosemite Climbing Museum, 5180 Highway 140, Mariposa; yosemiteclimbingmuseum.com. Call (209) 742-1000 or email yosemiteclimbingmuseum@gmail.com for information on when the museum is open. Tours available upon request.

Yosemite Mountaineering School and Guide Service, 9020 Curry Village Drive, Yosemite National Park; (209) 372-8344, travelyosemite.com. Founded in 1969, the school offers lessons in the park for beginners (climbing 60 feet up the base of a cliff and rappelling down), intermediates (crack climbing) and experts (big-wall climbing). Guides for individuals and groups are available too. T-shirts with the school’s “Go Climb a Rock” slogan remain one of the park’s top-selling souvenirs.

Mountain Shop at Curry Village, 9020 Curry Village Drive, Yosemite; (209) 372-8396. Stocks route maps, ropes, carabiners and the requisite sticky-rubber boots — as well as that chilling compendium of climbs gone terribly wrong, “Off the Wall: Death in Yosemite.”

Yosemite overnight climbing permits, (209) 354-2025. A pilot project started this year requires climbers to register for a free permit if they plan to spend the night on Yosemite’s walls. You can apply as early as 15 days and as late as four days before the start of your climb. You must pick up the permit when you enter the park. yosemite.org/climbingpermits

Tavern at Evergreen Lodge, 33160 Evergreen Road, Groveland, Calif.; (209) 379-2606, evergreenlodge.com The retro, wood-paneled bar at this 100-year-old resort next to the park is the ideal place to tell tall tales of the climb that was. General manager Nick Simon is a former climber with a soft spot for the kind. evergreenlodge.com

Yosemite Bug Rustic Mountain Resort, 6979A California 140, Midpines, Calif.; (209) 966-6666, yosemitebug.com. The hillside resort not far from the park offers berths in bunk rooms, single rooms and cabins; good for groups too. The dining hall serves up some of the best food in the region, centered on a huge hearth. It’s full of chatter, kids, board games and old Yosemite bric-a-brac. The mixed hostel and inn vibe will remind you of European mountain towns. Dorm room beds from $49, cabins from $85, suites from $160.

Stronghold Climbing Gym, 650 S. Ave. 21, Los Angeles; (323) 505-7000, strongholdclimb.com. Most would-be climbers practice at a local gym before trying their mettle on Yosemite’s granite walls. The couple who own this Lincoln Heights gym, climbers Katharine Mullen and Peter Steadman, are longtime Yosemite regulars as are many of its instructors. It uses the Yosemite Decimal System to rate difficulty, the same system used in the park. Chelsea Griffie worked out in this airy converted 1904 power plant before besting El Cap, becoming the first Black woman to do so.

A brief history of climbing in Yosemite

1905: First recorded climbing death (of about 130 to date) in Yosemite National Park. Experienced mountaineer Charles Bailey, 60, slid off El Capitan’s west cliff as his climbing partner watched.

1950: Blacksmith John Salathé and Allen Steck are the first to climb the north face of Sentinel Rock, using steel pitons Salathé made to suit the long parallel cracks of Yosemite’s rock faces.

1957: A team led by Royal Robbins becomes the first to climb Half Dome’s northwest face.

1958: Warren Harding takes a team up El Capitan’s nose.

1973: Yosemite climber Yvon Chouinard founds Patagonia, an outgrowth of his business forging metal climbing gear. It becomes a multinational company, which, in 2018, showed net sales of about $356 million, according to the Statistica website.

1978: Experienced climber James Adair, 20, and fresh from appearing on the cover of a climbing magazine, attempts to free solo Sentinel Rock. He slipped and fell 300 feet to his death.

1989: Mark Wellman, paralyzed years earlier in a climbing accident, becomes the first paraplegic to ascend El Capitan.

1994: Lynn Hill becomes the first person to free climb El Capitan’s nose.

2003: Yosemite’s Camp 4, a longtime climbers’ stomping ground, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

2004: Ken Yager founded Yosemite Facelift, which has become an annual event in which climbers clean up trash from the base of the cliffs and along common routes.

2015: Tommy Caldwell and bouldering star Kevin Jorgeson become the first to free climb El Capitan’s sheer Dawn Wall.

2017: Alex Honnold becomes the first (and still only) person to reach the top of El Capitan by free-solo climbing (without ropes).