In her earliest memory of the social Internet, Patricia Lockwood is a pious Midwestern teenager, posting her poems about Jesus having sex with mermaids on a forum called the International Poetry Pages. She can still picture the webpage in her mind’s eye: its custard yellow background, its anonymized flock of autodidacts, its old-school interface for submitting and commenting on poems.

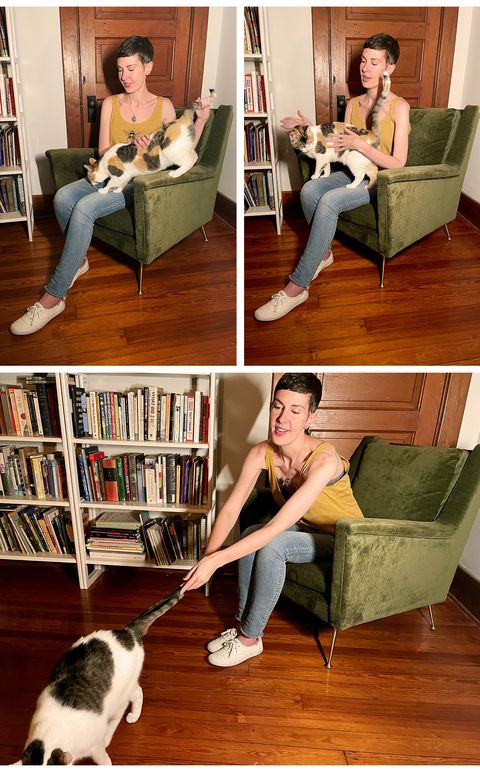

“There was a sense of real community, even though everyone was anonymous,” Lockwood says, Zooming from her bed in Savannah, Georgia, where her cat, Miette, sniffed inquisitively at the edge of her screen. “There was excitement that you could put something out there, and that people could respond all over the world in real time.”

Two decades later, Lockwood writes less about Jesus and mermaids than she once did, but the kinetic call and response that characterized her early years online now seems a blueprint for the forces animating her outstanding debut novel, No One is Talking About This, a visceral rendering of an influencer’s life in “the slipstream of information.” Though No One is Talking About This is Lockwood’s first novel, it’s also a culmination of a life made and unmade online, beginning with Lockwood’s transformative “deprogramming” from her conservative Catholic upbringing (memorably captured in her acclaimed 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy), courtesy of deep dives into progressive websites about infertility and late-term abortions. At nineteen, Lockwood met her now-husband in a poetry chatroom; at twenty-one, they married, and Lockwood set about seeking a wider audience for her poetry. When she joined Twitter in 2011, she soon amassed a devoted following enamored by her surreal, playfully raunchy “sexts”: gnomic shards of poetry combining erotica and webspeak. Take, for example, this 2011 sext: “I am a living male turtleneck. You are an art teacher in winter. You put your whole head through me.” Zooming with Lockwood is a delightfully antic experience, pinballing through asides about her love affair with GAP sweatsuits, digressions about how the pandemic saved us from the return of low-rise jeans, and attempts to tantalize her cat with coconut water. Her sense of humor is as manic and winning offline as it is online, all of it leavened with warmth and vulnerability.

Though Lockwood published her first collection of poems with an independent press in 2012, she erupted into the mainstream literary firmament in 2013 with the publication of “Rape Joke,” a tragicomic poem about a traumatic experience from her teenhood that became a viral sensation—a proto-”Cat Person,” if you will (which itself receives winky acknowledgment in No One Is Talking About This). The Guardian credited Lockwood with “casually reawakening a generation’s interest in poetry,” and soon widespread recognition followed, with Lockwood’s second book of poems, Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, landing to great acclaim; Priestdaddy’s critical victory lap would follow three years later. Lockwood, 38, now lives a Proustian and somewhat less online existence, writing from the comfort of her bed. “It’s where I do all my writing, good and bad,” she says wryly.

No One Is Talking About This is a profoundly autofictional novel—an outgrowth of Lockwood’s experience of viral fame, written in elastic Internet patois inflected with a poet’s sublime sensibility for language. It’s also Lockwood’s answer to the ambitious formal challenge facing contemporary fiction: how to bring the firehose of social media into the coddled analog domain of the novel? In the first half of No One Is Talking About This, a nameless influencer travels the international speaking circuit on the back of a viral tweet: “Can a dog be twins?” Her world narrows down to the portal (the “round, vaginal” term that Lockwood, a synesthete, coined for the internet), where the manic “blizzard of everything” constantly snows her under. Lockwood’s portal is a place of coexistent profanity and profundity, where borderline holy moments of togetherness within a “communal mind” are juxtaposed against the absurdity of familiar viral episodes, like the backlash against a much-maligned hotel that offered mini muffins to honor those killed on 9/11. Life in the portal soon infects our protagonist’s experience of the material world; a historic supermoon looks to her like “a very thicc snack,” while the closest thing to spiritual transcendence she experiences is burning her “b’hole” with essential oils. It takes a family emergency—her sister’s high-risk pregnancy and the birth of her niece, diagnosed with a life-threatening genetic disorder—to reawaken her to the world beyond her screen, where she’s reminded that the portal can’t contain the wonders and horrors of lived reality.

No One Is Talking About This enters a siloed world where our relationship to technology is more deranged than ever, and where all that tethers us to social experiences is the parasitic communion between user and platform. As Lockwood’s prescient protagonist muses, “This did not feel like real life, exactly, but nowadays what did?” Like Lockwood, we are both critics and captives of the Internet, glutted on an endless regimen of castigatory articles about the dangers of screens at night, but powerless to stop scrolling during the blue hours before bedtime. No One Is Talking About This is a miraculous rendering of an entire generation’s “internet poisoning,” but in its harrowing second half, it questions the limits of what online life can capture, calling for us to reawaken to the material world’s painful splendor. As the novel’s latter half reminds us: “There is still a real life to be lived.”

No One Is Talking About This began in the spring of 2017, when Lockwood became enthralled with Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban while avoiding packing up to move apartments (“I don’t like to help,” she jokes). In Mrs. Caliban, a lonely housewife is up to her elbows in dishwater when she becomes enthralled by a radio program about an escaped sea monster. Lockwood was captivated by how Ingalls punctured the corporeal mundanity of housework with the radio broadcast.

“Maybe I could write a novel like that—one that actually talks about the radio broadcast of our time,” Lockwood says. “We’re on our phones for hours every day, but we’re still acting in our novels like that’s not true. What if you brought the broadcast into the novel, and you wrote about it in a very daily way?”

Written in a style at once lyrical and fragmentary, brimming with memes and texts, No One Is Talking About This submerges us in our protagonist’s daily doomscroll, where the flotsam and jetsam of life in the online groupthink ebb and flow through her addled mind. Political outrage churns in the portal, with the daily trespasses of “The Dictator” blaring in the background; meanwhile, the discourse flattens, as a toxic uniformity bleeds into the language. The protagonist’s world hurtles at us as a kaleidoscopic decoupage of images, jokes, memes, news items, and video snippets, all of it blisteringly and subversively funny as only the “poet laureate of Twitter” could be. Lockwood wanted the novel to induce the sensation of Alice in Wonderland’s disorienting fall down the rabbithole, checkerboard walls blazing dizzily on all sides. If it sounds narratively amorphous, that’s because it is; at one moment, the protagonist laughs to herself, “The plot! That was a laugh. The plot was that she sat motionless in her chair.” The fragmented form came naturally to Lockwood, a self-described “magpie” who carries a notebook full of fragments.

“If you’re going to write a novel about the Internet, I think it has to take that form,” Lockwood says. “It has to have that shock of surprise of the next thing you encounter being totally unexpected. It was a really interesting formal challenge, but it was the only way to do it. It’s both an amazing innovation on my part and also totally inevitable.”

On the Internet, everything about a person’s life is material, from the impressive to the embarrassing—it’s all just content fodder. That’s not so different from fiction, where lived experience can be mined into art. Lockwood sees a synergy there, noting that a writer’s life is more available for public consumption than ever before, though the breathless literary discourse about autofiction fails to impress her.

“Autofiction is just the word we’re using now for a thing people have been doing for a really long time,” Lockwood says. “I think we’re in a position to better be able to tell when something is autofiction because people’s lives are more online. You can go back through my timeline and see where the real me is experiencing things that eventually make it into the novel. That hasn’t been consistently true; we haven’t been able to see into other people’s lives in that way. I think that’s why the conversation about it is so frenetic and heated. In order to have these conversations, we always have to pretend that these things are new.”

Midway through the novel, the protagonist receives a heart-stopping text. “Something has gone wrong,” her mother writes. “How soon can you get here?” Reality blots out the portal; she alights from Vienna to her sister’s bedside in their Ohio hometown, where life soon narrows down to a battery of tests and ultrasounds. Specialists reveal that the pregnancy is threatening her sister’s life, while the baby may not survive past delivery. This, too, is autofiction—Lockwood’s sister gave birth to a daughter with Proteus Syndrome, Lena, who passed away at six months old after a short, but much-loved life.

The protagonist and her family must contend with dogmatic pro-life laws criminalizing induced labor as a life-saving measure; as Lockwood writes of that legislation, “the worst seven words in the English language: there was a new law in Ohio.” For Lockwood, who as a young child saw her father arrested while demonstrating for the pro-life movement, butting heads with her parents about her sister’s medical care brought the conservative rhetoric of her childhood careening back into view. While on a business trip to Los Angeles, two weeks before the 37-week juncture at which her sister’s labor could legally be induced, she remembers screaming at her mother on the phone, her indignation about her pro-life upbringing rushing back as sister’s life hung in the balance due to restrictive conservative laws.

“You have to step out of that and see the larger reality,” Lockwood says. “Sometimes, you see it in the face of a person you love.”

As the due date looms, with a pall of confusion and grief settled over the family, the protagonist and her sister swap memes; at night, they watch episodes of River Monsters, a wildlife series about extreme anglers. The refrain that thrums through the novel rises to meet them: “For whatever lives we lead, they do prepare us for this moment.” The chaos of the slipstream has provided the sisters with a shared language of comfort, ready-made for deployment in this time of need—a language that Lockwood insists is valid and truthful, no matter its absurdity.

“There’s no such thing as a false life,” Lockwood says. “When you hit a life and death scenario, everything you’ve experienced prepares you for that moment. I think we’re an adaptable animal—maybe the most highly adaptable animal the world has ever seen. This is what we do. We slip into new forms, and our substance remains the same.”

One might expect the protagonist, abruptly severed from life in the portal, to sneak moments alone with her phone, refreshing her feed in the bathroom like a drowning woman. Instead, she is absorbed body and soul into the family emergency, no detox required. She does not dismiss the portal, but simply transcends it; Lockwood writes, “The previous unshakable conviction that someone else was writing the inside of her head was gone.” Our humanity is not absent in the portal, Lockwood suggests, but sometimes, our humanity is needed elsewhere. Lockwood experienced something similar following the frightening diagnosis in her own family.

“It’s an animal switch,” Lockwood says. “It was a reflex for me. My body knew how to be where it was needed. Maybe before, it was a problem that my body wasn’t needed. Maybe that’s why I was putting it in the portal. In the second half of the novel, when the protagonist is called, she’s able to respond. You might look at Twitter in the bathroom, dip into the timeline for a minute, but otherwise, you’re there. You’re at the hospital; you’re at the other end of your phone. You’re the hands that lift and carry.”

Against all medical predictions, the protagonist’s niece is born—and she lives. Life in the portal vanishes, leaving only “the rawness of life with the baby.” The protagonist’s days are filled with the miraculous intimacy of caring for her niece, an observant and curious child, who by the fact of her medical condition “would live in her senses,” would “only know what it is to be herself.” The baby’s life is one of sensory splendor, full of kisses and kicks and cries, antithetical entirely to unbodied life in the portal. This time is a reverent, urgent, intensely private chapter in the narrator’s life, where everything else falls away. Though some details are fictionalized, Lockwood sought to memorialize her niece’s life and personality in these pages, describing the writing process as a spiritual compulsion.

“The book became a cradle for her,” Lockwood says. “When it was happening, I couldn’t physically keep myself from writing about it. The animating force of the first half is that if we don’t write this down, we will lose it. That became even more powerful in the second half. Who will know what she was like? Who will know what her life was, if I do not, at this point in history, write this down?”

As the days slide by, the protagonist ruminates on the world she’s eager for her niece to experience: “How it felt to go to a grocery store on vacation; to wake at three a.m. and run your whole life through your fingertips; first library card; new lipstick; a toe going numb for two months because you wore borrowed shoes to a friend’s wedding.” The family seeks to bring as much joy as possible to the baby’s one wild and precious life, transporting her and her bevy of medical equipment to the zoo, beaming “Over the Rainbow” into her ears, even taking her to Disney World. Lockwood sees the novel as an extension of that process—a way of bringing Lena to meet the world.

“My sister and my brother-in-law always brought her out,” Lockwood says. “It was very difficult to do. She had a lot of machines, she had oxygen, and she had to be positioned in certain ways. But it was something they always made sure to do. I think the book is part of that. It’s difficult; it’s unwieldy. It’s surrounded by oxygen tanks, but it’s worth doing.”

In one touching scene late in the novel, a philanthropic organization brings a poodle to the hospital to meet the baby, after the protagonist has long been adamant that her niece must meet a dog. Lockwood writes, “The dog ate her fingers one by one—strange, how everything in the entire world wanted to do that to a baby.” In Lockwood’s own life, the dogs who attended her niece at the hospital later joined them at her wake (“that’s something the Internet would love,” she jokes). Corporeal pleasures are the heart and soul of the novel’s second half, from games of patty cake to sweet gurgling, all of it bathed in the flowering of love and tenderness that blooms within our narrator. It’s a bittersweet, transcendent contrast to life in the portal—one that only someone who’s lived fully in the material world’s fantasia of senses could write.

“We’re here for such a short time,” Lockwood says. “You hear a little bit of music, you get to meet some dogs, you get to hear Marlon Brando’s Wikipedia entry. It’s worth doing all of these things. It’s worth bringing the world to someone if they can’t run out to meet it themselves.”

In the wake of her family’s loss, Lockwood found her relationship to the Internet profoundly changed. “I couldn’t really be online in the same way,” she says. “I couldn’t be as plugged in as I was before.” Yet to ask if the Internet is “bad for us” is to misunderstand the novel, she insists; rather, the siren song of the portal will always call us back, as our experiences there have reshaped how we understand the world around us, and our place in it. Perhaps it’s best understood as the “communal mind,” as Lockwood describes it—one we can dip in and out of as our analog lives allow.

“People ask me, ‘Are you going to leave the internet entirely?’” Lockwood says. “Sure, until the next time a wolf shaman tries to overthrow American democracy. At that point, I’ve got to get online and see what’s going on. It might not be Twitter. It might be some other platform, some other panopticon, some other eye, that we’re going to be living inside. But it’s hard to give it up completely, because that’s the way we see now—through the million facets of the eye and all of us looking together.”

Isolated at home in Savannah, Lockwood, like so many of us, is missing the material world. She’s missing rowdy readings, book tours, handshakes, hugs—the tangible sweetnesses of literary life that any debut novelist should get to enjoy. During the pandemic, the Internet has allowed us to experience the world and one another, but some holes, it just can’t fill. Like holding babies—”of all the things that have been taken from us!” Lockwood exclaims indignantly. Yet mere days before her book launched, Lockwood became an aunt another time over when her sister and brother-in-law welcomed a new child: their son, Liam. Once the all-clear is granted, Lockwood can’t wait to hold her nephew, and to smell his downy head. You could type “baby smell” into the portal, she supposes, and the meaning would be understood, but nothing compares to the real thing.

“That’s the thing you get in the material world,” Lockwood says. “That’s what elevates this life above that one. We get to smell those babies’ heads.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io