When traveling the roads of El Salvador, it’s common to see light blue ads splashed across billboards and buses, a color that identifies the New Ideas party that on Sunday feb. 28 will compete for the first time in elections for mayors and members of congress.

Beyond its ubiquitous color, the New Ideas (NI) electoral campaign revolves around the figure of Nayib Bukele, the “most handsome and cool president in the world,” as he proclaimed himself shortly after taking power on June 1, 2019.

Many believe that Sunday’s elections will be key to the future of this beleaguered Central American nation, which still is struggling to recover from its calamitous civil war of 1980-92 and the aftershocks of endemic corruption, inequality and drug-fueled violence. If Bukele secures the backing of a majority of legislators, from his own party and his political allies, critics say he will be able to consolidate an executive power that has grown increasingly autocratic, intolerant and militant.

Opposition parties and human rights workers denounced Bukele for dispatching federal troops on Feb. 9, 2020, to the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly to create pressure to approve a loan to purchase new security equipment. The ensuing scenes of armed soldiers invading the chamber stunned Salvadorans who remembered the brutal era when government tanks and helicopters mowed down civilians and guerrilla fighters, leaving at least 75,000 dead.

Tatiana Alemán said President Nayib Bukele’s interference in congress on Feb. 9, 2020, revived dark memories of El Salvador’s military dictatorship.

(Soudi Jiménez / Los Angeles Times )

But like other populists who’ve come to power in recent years, the 39-year-old president — a former mayor of the capital, San Salvador, who styles himself as a political pragmatist — commands a devoted following among those who distrust the ruling class and believe their country needs an independent strongman to shake up the status quo. According to one recent poll, 68.8% of respondents plan to support Bukele’s party in Sunday’s races.

“Bukele has a lot of social acceptance, [something] that had not been had before,” said Christopher Díaz, 20, who along with several other young people was handing out calendars, fliers and brochures with the president’s photo to passersby on a hot afternoon in front of the Plaza El Salvador del Mundo in San Salvador.

José Miguel Vivanco, a lawyer and director of Human Rights Watch’s Americas division, said the Biden administration must play a crucial role in curbing Bukele’s personality-driven, lawbreaking leadership. Bukele has disobeyed rulings of the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, among them those that prohibited him from confining people in containment centers for violating COVID-related quarantine measures, Vivanco said.

“He has promoted a hostile environment for the independent press and human rights organizations, using social media to attack and stigmatize them,” Vivanco added. “If his party wins the majority in the Assembly, my fear is that he will advance with a constitutional reform that allows him to further concentrate power in his hands and be reelected to try to perpetuate himself in office.”

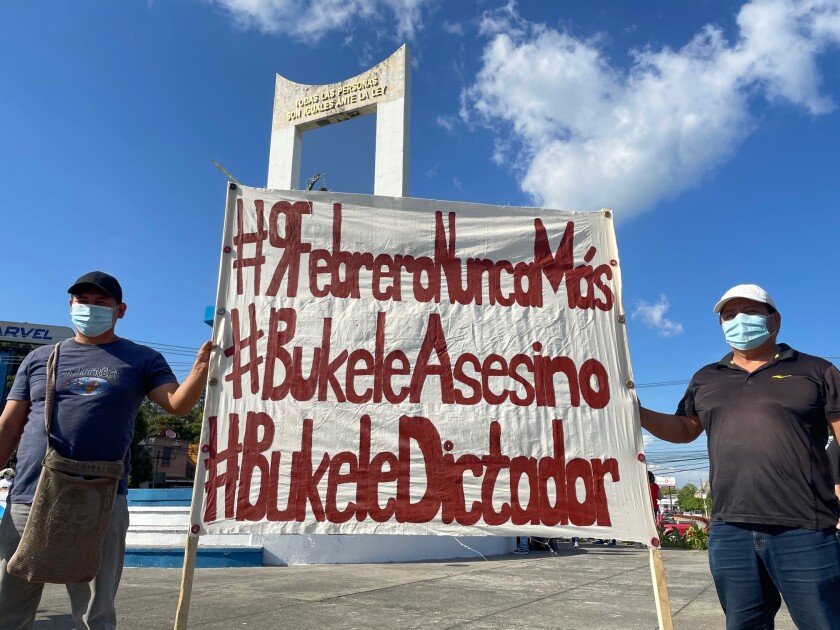

Two people in San Salvador hold a sign denouncing El Salvador’s president and his interference with the Legislative Assembly.

(Soudi Jiménez / Los Angeles Times en Español)

In the United States, which for decades has held political and economic sway over the country of 6.5 million, some members of Congress and foreign policy officials fear that giving Bukele more muscle could shatter El Salvador’s rule of law and separation of powers.

“I am very concerned about the conditions in El Salvador,” said U.S. Rep. Norma Torres (D-Pomona), who closely monitors Central America.

“I know that from the beginning the president has not had the [legislative] support,” added Torres, who is of Guatemalan heritage. “But that does not mean that we can abandon our responsibility to promote stability in El Salvador.”

Torres said that the Biden White House will pay greater attention to the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, and show greater concern for human rights and the rule of law there, than did the Trump administration.

“We have a president who is not going to tolerate dictators, a president who is not going to tolerate just sending money there without having any transparency, without having a security plan” and an immigration plan, she said.

Twenty months after taking office, Bukele is quite popular. According to a survey by the Francisco Gavidia University (UFG) in San Salvador, he received a favorable assessment of 8.8 on a scale of 10 for his handling of the pandemic, and his overall favorability ratings are comparable.

“He is a president who is quite armored,” said Óscar Picardo, director of the Center for Citizen Studies at UFG. “He has channeled that citizen unrest. He has pointed a finger at those who have been the culprits.”

Wary observers say that Bukele has followed a demagogic playbook. A publicist and businessman by profession, he was elected mayor of the small municipality of Nuevo Cuscatlán, in the state of La Libertad, in 2012. Before ending his term, he launched a successful campaign for mayor of San Salvador.

In both contests he ran as the candidate of the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) party, which after the civil war ended sprang from remnants of the leftist guerrilla organization that had fought the U.S.-backed government. But Bukele soon adopted an irreverent and critical stance toward the FMLN, an early step in detaching himself from his own party.

At the same time, he was gaining ground with Salvadoran youth through his mastery of social media. His favorite platform was Twitter, on which he founded his campaign to become president at the age of 37, the youngest in El Salvador’s history. After the FMLN expelled him in October 2017, Bukele began laying the groundwork for founding his own party. Through a series of maneuvers, he eventually joined the center-right Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA) party, which backed him for president. He founded the New Ideas party in August 2018.

Between 1989 and 2019, El Salvador was governed first by the extreme-right Nationalist Republican Alliance party, known as ARENA, and more recently by the FMLN. Corruption proliferated under both. Bukele took advantage of electoral apathy in a country sunk in poverty, insecurity and unemployment, the same factors that drive emigration. (According to the Pew Research Center, 2.3 million people of Salvadoran descent live in the United States.)

In the 2019 elections, Bukele got 1.4 million votes and was elected by only 25% of the electorate of 5.6 million voters. Absenteeism was above 50%.

Raúl Hinojosa-Ojeda, a political science professor at UCLA, said that in the Bukele government “authoritarian tendencies are emerging, and that is worrying.”

“He is attacking the party process and creating more of a cult of personality,” he added.

María Esposoria, who lives in the town of Perquín, El Salvador, is a former guerrilla fighter who says she will vote for the party of President Nayib Bukele on Sunday.

(Soudi Jiménez / Los Angeles Times )

On Sunday, voters will choose 262 mayors, 20 legislators to serve in the Central American Parliament and 84 legislators in the Salvadoran congress, known as the Legislative Assembly. Among those casting ballots will be María Esposoria, who settled in the northeastern municipality of Perquín in Morazán state, a former guerrilla stronghold near the Honduran border, in 1993, shortly after the bullets and cannons were silenced. The 57-year-old widow washes clothes for less than $30 a week to feed her children and grandchildren, who live with her in a house made of cement blocks with a tile roof and no sewage system.

Esposoria and her late husband fought on the side of the guerrillas during the 1980s; she made tortillas during the day and grabbed her M-16 at night. One of her eight children was born in the middle of a shooting. “The mortars were running over it,” she said.

But after voting for the FMLN for 10 years, the former combatant did not see any change in her living conditions. In this Sunday’s elections she will switch her vote for congress from FMLN red to NI light blue.

Esposoria’s vote is yet another that the left-wing FMLN will lose in Morazán. Here, in the 2014 presidential elections, leftist candidate Salvador Sánchez Cerén got 47,232 votes. But in 2019, the ex-guerrilla party received less than half that number, 23,102, while the right-wing GANA party won with 31,649 votes, helping to usher Bukele into the presidency.

“One is not expecting great things, but at least to see a little” improvement, Esposoria said in a resigned tone.

Like other populists, Bukele seeks to depict himself as a law-and-order figure, able to tame El Salvador’s terrifying drug gang brutality. In 2020, according to government reports, there were 1,322 homicides in El Salvador, a drop of 45% from the previous year.

“The reduction in homicidal violence is due to the strategy, policy and plan promoted by President Nayib Bukele,” said Ricardo Sosa, a criminologist.

Some Salvadorans say that police have indeed stepped up their presence in certain localities under the Bukele government’s “territorial control plan.”

“Now I see the patrols, the police make tours of the neighborhoods on foot. Before they didn’t even get” out of their vehicles, said Christopher Díaz, a student at the University of El Salvador.

However, according to other crime experts and the digital daily El Faro, homicides have dropped, at least in part, because representatives of the Bukele government negotiated with leaders of the MS-13 gang to increase benefits to incarcerated gang members, including not mixing members of MS-13 and its rival Barrio 18 in the same cell.

Further buffing his populist credentials, Bukele has captured the support of faith communities by cultivating an image of deep religiosity in a country where the proportion of self-identified evangelicals (39.5%) soon may overtake that of Roman Catholics (40.5%).

Mario Vega, general pastor of the Elim Christian Mission, suggests that Bukele — a descendant of Palestinian Christian, Catholic and Greek Orthodox grandparents, and whose father converted to Islam and became an imam — has successfully constructed a religious identity that serves his political aims.

“There must be simple people who are impressed by this type of performance,” said Vega, who leads an evangelical denomination with some 300 churches throughout El Salvador.

Critics contend that Bukele’s habit of concealing his government’s intentions and operations has been laid bare during the coronavirus crisis. To address the pandemic, Bukele’s administration distributed food baskets and $300 subsidies to some 1.5 million people. But, according to a report by the Court of Accounts of the Republic, $30 million in these government funds went to 100,000 people for unknown criteria.

“The [current] level of opacity, we have not had before,” said Roberto Rubio, executive director of the National Development Foundation (FUNDE), an expert on issues of public transparency and access to information.

Danilo Miranda, a political science professor at the Central American University in San Salvador, said Bukele is chipping away at institutions that could hold his power in check, such as the Supreme Court of Justice, the attorney general’s office, the Government Ethics Court, the Institute of Access to Public Information and the Court of Accounts of the Republic.

“We are approaching an authoritarian state, even with fascist features,” Miranda said.

On the afternoon of Feb. 9, a group of young people with white flags and yellow signs gathered at the Monument to the Constitution in San Salvador. “F9 Never Again” was written on a blanket, referring to the date a year earlier when Bukele sent troops into the legislative chamber.

“This arbitrary act can be classified as an act of bullying by President Nayib Bukele,” said Tatiana Alemán, a 30-year-old university student wearing a black shirt and a white mask over her mouth.

When Alemán was born, in 1990, the civil war was winding down and her pregnant mother commuted to her job in the center of San Salvador. “She had to go to work in the middle of the bullets,” Alemán said.

To Alemán, Bukele’s storming of congress last year evoked her country’s bloody and tragic past — and fear that those times could return.

“Those actions that supposedly stayed in the 1970s, and everything that led to the conflict, is now being seen,” she said.