“If you walked around Sanità 15 years ago with your camera on your shoulder like that it would’ve been stolen,” says local shopkeeper Antonio Vitozzi, pointing at my battered Nikon. More than likely I would’ve been nowhere near this neighbourhood back then. Riven by urban decay and high unemployment, Naples’ poorest district used to be a dangerous place where the Camorra held sway. It wasn’t just Italians afraid to come here but Neapolitans too.

Not these days, though. Sanità has undergone a quite miraculous transformation thanks to La Paranza, a cooperative of idealistic young friends who began running guided tours to Italy’s finest catacombs in the early 2000s. At the time, the only access to the catacombs was granted by the Catholic church for academic study.

Today, after significant restoration funded by La Paranza, the catacombs, alongside Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum, are a must-see Neapolitan attraction, and tourism to Sanità has inspired new guesthouses, restaurants and employment. In its 15th year, the cooperative is launching a new above-ground walking tour this December called Luce (light), featuring specially commissioned contemporary art in neighbourhood churches.

Sanità lies north of Naples’ historic centre. The walk there takes me along via Santa Theresa degli Scalzi, a long, straight road running towards the 18th-century Bourbon palace of Capodimonte. En route, I cross a towering bridge built in 1806, which came to symbolise the neighbourhood’s decline, because its construction saw this once affluent suburb slowly bypassed by merchants and dignitaries who could travel more directly between historic Naples and Capodimonte.

San Gennaro’s catacomb is found near a sugar-white church, a 1960s replica of St Peter’s in Rome. It’s here that Cooperativa La Paranza began guided tours to Naples’ two most important catacombs, Gennaro and Gaudioso – the only way to see either. Enzo Porzio, 36, one of La Paranza’s founders, tells me that by 2019 the catacomb tours were attracting 160,000 visitors a year.

As a teenager with poor employment prospects, Enzo and his neighbourhood friends in Sanità were galvanised by the arrival of a progressive clergyman, Antonio Loffredo. “We were young when Father Loffredo permitted us to start tours in the catacombs,” he says. “At this time, we were asking ourselves what we could do as adults: should we leave Naples to work, or do something to help our community? There was much prejudice against Sanità.”

After several years spent guiding as volunteers, making money only from tips, they established La Paranza in 2006 to formally launch paid tours. “As tourists came, the project started to change the neighbourhood. The Camorra’s influence weakened. We created a new environment for arts, theatre, culture and archaeology to flourish. From a no-hope neighbourhood, local people saw new opportunities.” The cooperative now employs 40 guides and in 2014 was a founder member of the San Gennaro Community Foundation, which finances social enterprises across the neighbourhood.

Guided tours to the catacombs last an hour. I’m led underground into San Gennaro’s by Antonio Iaccarino, who now trains youngsters joining the project.

Gennaro is Naples’ patron saint. Beheaded for his Christian beliefs in AD305, his remains were brought to Naples in the fifth century and his catacomb became a pilgrimage site. His bones were stolen and taken to Benevento 400 years later, before being returned to Naples in 1491. His sainthood was reaffirmed in 1631 when the parading of his relics were said to have halted an eruption of Vesuvius that threatened Naples.

Carved from Naples’ soft volcanic tuff, this catacomb dates to the second century and expanded once Gennaro was interred here. Entering the upper level, I feel lilliputian strolling through a forest of toadstools – the rounded stems of tuff supporting the ceiling of the Basilica Adjecto, where pilgrims once shuffled past empty tombs cut into the walls and arcosolia with sumptuous murals for the wealthy elite. All bones were removed in the 1960s to a nearby ossuary.

One ornate mural depicts a sixth-century dignitary, Theotecnus, with his wife and daughter, who died aged two years and 10 months. “He would’ve been rich, because the mural was altered throughout as the family died,” says Antonio. San Gennaro’s own tomb is marked by a crosier, or bishop’s crook. It was rediscovered in 1973, long after the catacomb had fallen out of use.

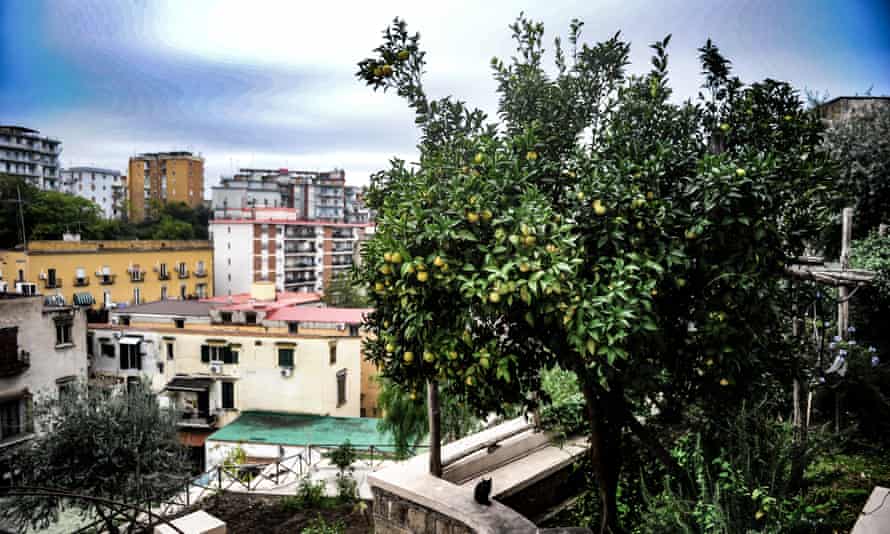

The catacomb’s exit purposefully directs visitors towards downtown Sanità, where I’m immediately struck by its authentic intensity. Little shops and tenements fill every space. The lights twinkle on votive shrines. Conversations are suspended mid-air, shouted between balconies of buildings adorned with murals, graffiti, and often piles of rubbish. Sanità’s centrepiece is a colossal Dominican basilica, Maria della Sanità, built in 1610, which physically fuses with the brick uprights of the overhead bridge. The basilica’s side chapel hosts La Paranza’s first ever accommodation, Casa del Monacone (doubles from €50 B&B). The six rooms are so popular I couldn’t get a bed.

“Sixteen years ago, when this opened people asked, ‘Who would want to stay overnight in Sanità?’,” shrugs Giuseppe Iaccarino, its manager. “But now Sanità has several hundred Airbnb. It helps locals get by renting rooms out and tourists to stay longer and spend more money,” says the young entrepreneur, soon to open his own restaurant.

One trader benefiting from increased visitors is Antonio Vitozzi. His family butcher’s began in 1823. “Who would’ve thought a few years back I’d be selling fancy meat at €50 a kilo – locals just didn’t have the money. Now people from the posher parts of Naples come here to shop,” he says. He invites me to his Friday steak night. I haven’t the heart to tell him I’m vegan.

But it’s the reduction in violent crime that’s aided Sanità’s reputational change. Antonio points me towards a memorial to 17-year-old Genny Cesarano, a lifelike depiction of the teenager adorned by the letters S.A.N (saint). He was murdered in 2015 during a drive-by Camorra shooting. “Things had been getting better, so the community was shocked by this. Next day, 5,000 of us came onto the streets to demonstrate [that] we’d fight to maintain the gains we’re making,” he adds. Subsequently, Camorra activity in Sanità withered away.

Those gains include impressive developments of the arts. Funded by the community foundation, La Paranza is now hiring three more guides for its new walking tour, Luce, featuring commissioned contemporary artworks by renowned artists in Sanità’s poorest subdistrict, Cristallini. It will feature pieces in deconsecrated churches, the tour beginning at Sant’Aspreno ai Crociferi, where maverick Italian artist Jago will install a sculpture entitled Pieta. One piece, Veiled Boy, is already installed in San Severo Church: a touching frieze of a child covered by a translucent shroud laid out on a tomb. The child’s face is frozen in anguish. “Jago was influenced by the image of a migrant boy’s body washed up on the coastline,” says Antonio.

Elsewhere, the local youth orchestra, Sanità Ensemble, practises in San Severo, and I meet budding actor, 24-year-old Ciro Burzo, at Teatro Sanità – another church gifted by Father Loffredo. Rehearsals are under way for La Rosa del mio Giardino, a play about Dalí’s love letters.

“I’m a kid of Sanità,” says Burzo. “There seemed only one way out of here, to be good at football, and I wasn’t. The arrival of the theatre came about because visitors needed night-time entertainment. It’s changed my life, my self-belief,” he says.

Back on the tour, I return underground into San Gaudioso’s catacomb, which shouldn’t be missed. This Carthaginian bishop was forced into exile by the Vandals, settled in Naples and died around AD450. The catacomb is entered through a portal cut into the majolica-tiled floor of the basilica. It dates back to the fourth century and possesses outstanding ancient frescoes, although it’s the later 17th-century ambulatory that’s unforgettable. Here, the tomb walls portray the dead – once wealthy patrons of the basilica above – as skeletons, with a void where their heads would’ve been, which once hosted their actual skulls. It reminds me of a danse macabre. The female murals wear skirts and one epitaph translates: “Beauty is not immortal, time takes everything”.

“In Naples we have a weird cult worship of purgatory. People revere the bones of the nameless dead, the pezzentelle, to help them depart purgatory for heaven, but in return expect their grace and favour. It’s like buying a lottery ticket,” laughs Antonio. “But in 1969 Cardinal Ursi deemed it idolatrous and such sites of reverence were closed. The skulls at this catacomb were cut out. But the cult still continues in Naples.”

Another Neapolitan church, Purgatorio ad Arco, maintains shelves of skulls in its crypt. But I end my stay at Naples Cathedral, visiting the reliquary of Gennaro, a baroque chapel housing a bone fragment of his. Two sealed ampoules of his blood are kept beneath the duomo’s altar and produced three times yearly to be declared miraculous when they liquefy from their solid state. Yet San Gennaro’s true miracle is how his presence in death has helped foster the resurrection of Sanità.

Guided tours cost €9 for a combined ticket to the catacombs of Saints Gennaro and Gaudioso, catacombedinapoli.com