On the Shelf

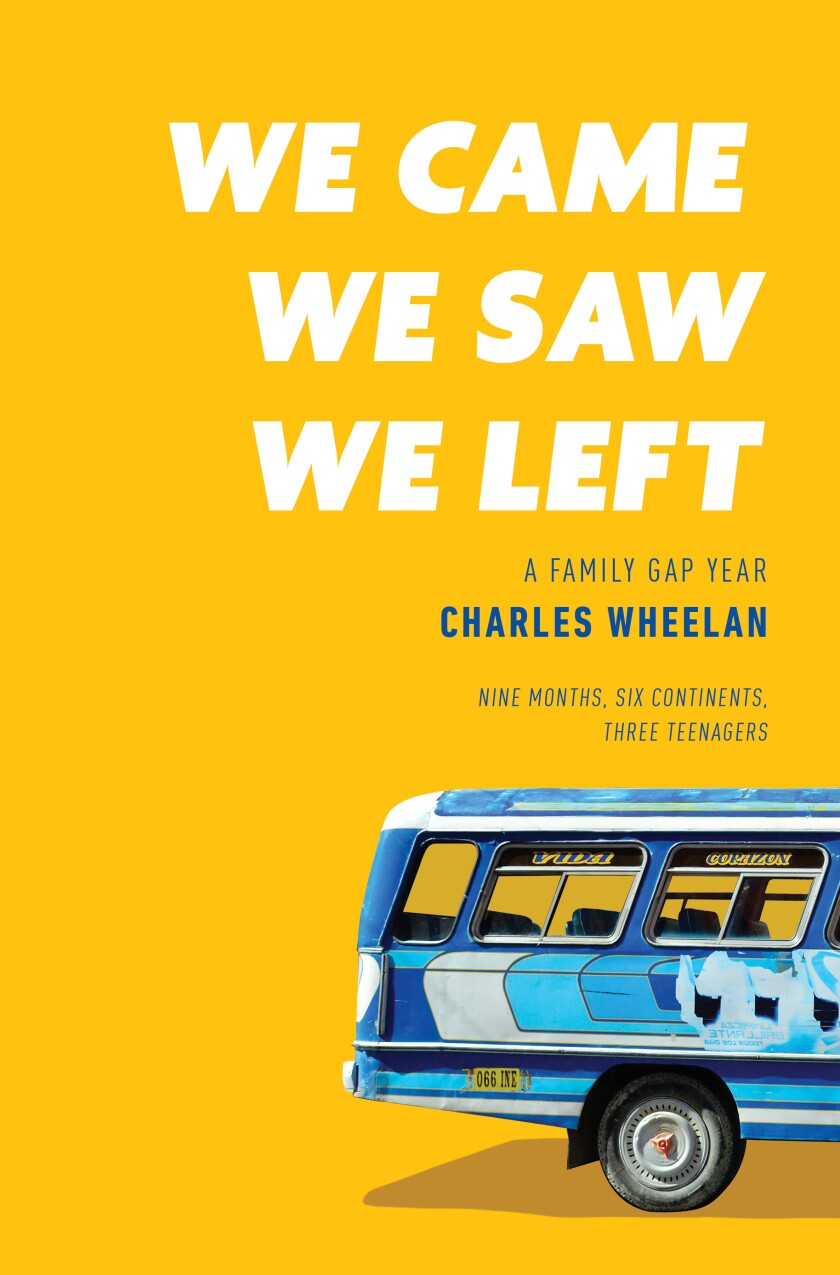

We Came, We Saw, We Left: A Family Gap Year

By Charles Wheelan

Norton: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Katrina, a bright high school graduate — eldest child of former Economist correspondent Charles Wheelan — tries to enjoy the family’s time in Bhutan, but there’s an infection on her ankle that’s looking worse by the day. Eleven-year-old CJ, the youngest Wheelan, usually can be found on the floor, crying. Sophie, the middle child, is in danger of failing her sophomore year in high school and has threatened a hunger strike by handwritten letter. There’s also the matter of a multi-entry visa to India: Katrina has only nine fingers, and the Kolkata bureaucracy requires a full set of fingerprints. Wheelan’s wife, Leah, meanwhile, insists the family “fun money” has run out. No more afternoon coffee.

This single passing moment is a fair illustration of the dizzying blend of tension, charm, silliness, headlong risk and occasionally transcendent profundity of “We Came, We Saw, We Left,” Wheelan’s memoir of an epic nine-month family “gap year.”

You might ask yourself: Do we need a book about an epic voyage, when we’ve all been trapped on a couch for the last 10 months?

Before embarking on a journey that takes them from Colombia to the Galapagos, East Africa to Vietnam, Wheelan, a lecturer at Dartmouth, and his wife, a public school math teacher, assess their comfortable lives and decide (a few months before the election of Donald Trump, years before COVID-19): Yeah, let’s blow it up.

The Wheelan family poses for a selfie at a deserted Machu Picchu, in Peru.

(Charles Wheelan)

When Wheelan outlines their reasons for leaving, it’s hard not to agree — at least, for this quarantined moment, in principle. “Because we needed/wanted a year to recharge and reflect … Because taking time off can be a great career move … Because global travel would be an invaluable part of our children’s education … Because I am a huge proponent of high school graduates taking a gap year … Because it is much, much cheaper than you think.”

How cheap? It will cost Wheelan, he estimates, only one year of deferred retirement — “hardly a life-changing sacrifice.” And so the Wheelans temporarily rehome their two dogs, rent out the house, take job leaves and arrange remote schooling for their children (something that now takes no arranging at all). Thirty minutes after landing in Cartagena, Colombia, they’ve bought an empanada from a street vendor, in flagrant defiance of the infectious diseases nurse back in New Hampshire, who had said: “No street food.”

More rules are broken. Lessons are learned; chief among them is that travel is wonderful and brutal — often wonderful because it’s brutal. A rail strike in Peru means the family must hike five miles under the cover of darkness but gets to enjoy a deserted Machu Picchu. On two occasions, Wheelan focuses his camera on a cool-looking bug in the Amazon “only to have it attacked by another insect.” They quickly (or slowly) discover the “best innovation” in Tanzanian bus travel — “Drivers can be fined if they arrive at a destination too quickly. It is a clever way to enforce speed limits.”

At times, the book can feel like a list of reasons not to travel: They lose the kids in Medellín, Colombia. There are numerous CMFs (Complete Family Meltdowns). CJ becomes convinced his male anatomy will explode at the Great Barrier Reef and Sophie really does come close to failing sophomore year. Oh, and there’s Katrina’s weird infection.

CJ Wheelan on a trampoline with new friends in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, from “We Came, We Saw, We Left.”

(Charles Wheelan)

An obvious comparison is to 2019’s “How to Be a Family,” by Dan Kois, which found another American mother and father taking their kids on a global survey of how other families function. But in Kois’ telling the family methodically spends three months apiece in Costa Rica, New Zealand, Kansas and the Netherlands. Insightful as Kois could be on the long rhythms of actually living somewhere new, it’s easy to imagine the Wheelan clan scoffing at the meandering Koises, perhaps with a cool new acronym. (DKITS: Dan Kois is too slow.)

A skeptical reader might wonder why the Wheelans have brought nine months of manic travel upon themselves and one another. (The fear of private-part explosion stems from Wheelan’s own practical joke, taken too far.) Readers might also wonder why they should care. Wheelan, gifted with his generation’s most privileged class and ethnicity, seems armed with the belief anything he thinks, says or does is pretty interesting. After all, he attended the same high school as filmmaker John Hughes, America’s master of the ordinary, and actual classmates served as extras in “Sixteen Candles.”

At worst, we are in able if occasionally cheesy hands, trapped inside a too-long feature in Hemispheres magazine. Maybe a nice friend could have told Wheelan to elide some details, like the fact it was his idea to have his son stand over a geyser of hot air, simulating flatulence for a photo. I didn’t love it when, for a laugh, he suggested his prepubescent son tell a nurse he might have gonorrhea, nor did I relish this lumpen witticism: “I will admit I am a modern art skeptic; I find a lot of it incomprehensible and silly. Why is it art if you put a knife in a bowl with two live goldfish?” We know art when we see it, Charles. This ain’t it.

An author of numerous popular textbooks about economics and public policy, Wheelan overcomes such problems because he is a skilled craftsman; the anecdotes start to feel curated and hard-earned. It’s not just accuracy or verisimilitude; from set pieces in Vietnam and Chile and Tanzania to memories of previous trips and life in Hanover, N.H., Wheelan gets better and better about pacing, up to and including the chapter titles and enticing subheads. (“To recap: If everything went well, our journey would be rickshaw, bus, overnight train. Everything did not go well.”)

The best aspects of the book — less P.J. O’Rourke and more Dave Barry — make us fall more and more in love with the family as they develop a kind of wartime camaraderie. There’s so much work under any circumstances to complete the daily, hourly or even minute-to-minute dance of making a family work, but the process is that much more intimate and dramatic when the task at hand is to outrun a deranged tout on the Bolivian salt flats.

Are we at our best while in harm’s way? It’s easy to find the idea exhausting in 2021, when we’re mostly stuck at home, while actual citizens of America attempt to overthrow the government and express their inalienable right to flout basic safety orders. But Wheelan’s writing is too engaging, insightful and downright pleasant to dismiss entirely. Also: A negative review, it’s hard not to imagine, might result in a downright unpleasant visit from at least one angry Wheelan.

A melancholy gloom hangs over any book like this, because every trip must end. Yet Wheelan lends a new gloss to the impending resumption of normal life. The dogs, having returned to the house, fall asleep in the usual places. The kids move out. A new routine forms. For many months after the trip, Wheelan admits, he can’t even look at the newspaper’s travel section.

In any event, we can cling to this: “Some countries will become harder to visit, or less safe; others will become more accessible,” Wheelan writes. “One thing will never change: Fortune favors those who get their passports and go.”

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”