The cows clocked us as we started across a neighbouring field, and by the time we reached the stile a dozen beasts – some with pointy horns! – were jostling for an eyeful, snorting and stamping an occasional hoof. Continuing would have meant shouldering our way through the herd. We plucked up the courage to go on once the cows lost interest, but our townie fright at these gentle, curious creatures might have wrung a smile, even a wry verse or two, from the man whose writing had brought us to this part of north-west Gloucestershire.

Robert Frost is a renowned American poet who won four Pulitzer prizes; what is less known is that he first found fame in Britain, and his poem The Road Not Taken was written right here.

Our route led – over more stiles, meadows and streams – to a village that, just before the first world war, gave its name to a revolutionary literary group. The Dymock poets, as they came to be known, rejected Victorian poetry’s high-flown moralising to write in simple language about everyday things.

Frost had always yearned to be a poet, and in late 1912 moved to England in an attempt to kickstart a literary career. It worked: two books of verse published in London won great acclaim. He fell in with writers Lascelles Abercrombie and Wilfrid Gibson, who were living near Dymock, and moved his family into a little black-and-white house a few miles away. Other poets, including Rupert Brooke and Edward Thomas, joined them, and all were enchanted by the area’s woods, farms and little valleys.

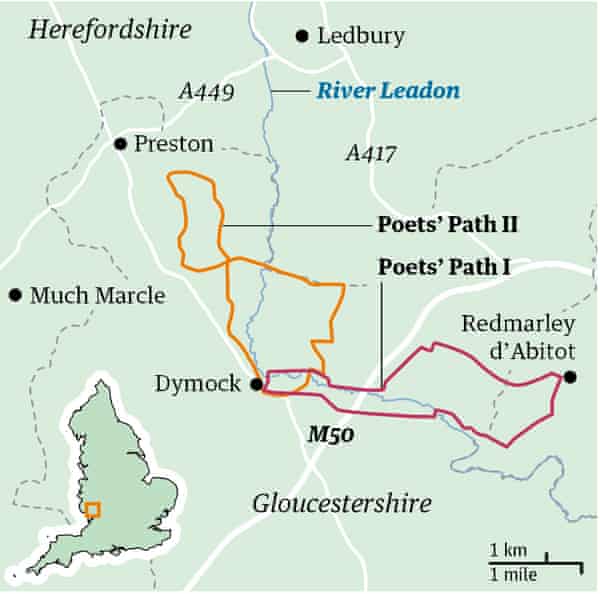

The idea of “less-travelled” trails has a particular appeal right now – and in late May we met just one dog walker in two days of hiking. Exploring the routes is easy thanks to the Windcross Paths Group, who maintain and signpost routes the poets are known to have walked. They publish guides to two circular routes – Poets’ Paths I and II – each about eight miles, and both now marked on the OS Landranger 149 and 162 maps.

Our holiday let in Broom’s Green, just north of Dymock, made the perfect base for communing with poetic minds. Stables Cottage is part of Horseshoe Inn House, once the village pub, and the story goes that on a ramble nearby, Frost and Thomas fell foul of a gamekeeper who threatened them with his shotgun, and dodged in here for a steadying glass of cider. The beam above the bar, complete with hooks for tankards, is still there in the cottage’s sitting room. The rare Old Gloucester cows that graze the field behind the garden belong to nextdoor neighbour Charles Martell, who uses their milk to make Stinking Bishop, officially Britain’s smelliest cheese.

The leaflets were useful, but we were glad of the OS app, with its arrow showing our exact location. Poets’ Path I is all intimate paths and ancient byways, and takes in the former home of Barbara Davis, who drew the leaflets’ exquisite maps. A hut in the garden is a free resource for walkers, with picnic tables and information. Next door is half-timbered The Gallows, where the Frost family stayed with the Abercrombies in 1914. The bridle path from here was glorious: lined with shoulder-high cow parsley between a steep wooded hillside and a meadow ablaze with buttercups. Further south, bluebells thronged a slope above the winding River Leadon. As the sun came out the land was, in Abercrombie’s words, “one great green gem of light”.

Path II takes in wide views often dominated by undeniably breast-shaped May Hill, topped by its “nipple” of trees, and several poets’ homes: Little Iddens cottage, which must have been a squeeze for the six-strong Frost family; and Oldfields, where Edward Thomas lived. I stopped here to ask for a drink and the owner filled my bottle with sweet-tasting water from the house’s own well. The Old Nail Shop is a corner cottage that was the setting for Gibson’s poem The Golden Room, in which the friends listen to Frost talking in his “slow New England fashion”, his “ripe philosophy” having the “body and tang of good draught cider”.

Frost was amused in later life by the philosophical meanings read into The Road Not Taken, which was in fact a dig at his dear but indecisive walking companion Thomas, who would always pine for sights not seen. “No matter which road you take, you’ll always sigh, and wish you’d taken another.”

The group’s Dymock idyll was short lived: by 1917, Brooke was buried in “some corner of a foreign field” (in Greece) and Thomas had been killed at the battle of Arras. Frost returned to the US and success, but said he “never saw New England as clearly as when I was in Old England”.

On our last day we ditched the leaflets and pushed through a hedge to follow a weathered footpath sign across a copse, in front of Georgian Haffield House, then over a broken stile to a pond at the foot of a secret valley. Toiling up to its rim, we stopped and gazed open-mouthed: the panorama stretched north to the dark tops of the Malvern Hills, and west in the setting sun to Marcle Ridge. Following the Poets’ Paths had been fun, but we found our best reward on one less travelled-by.