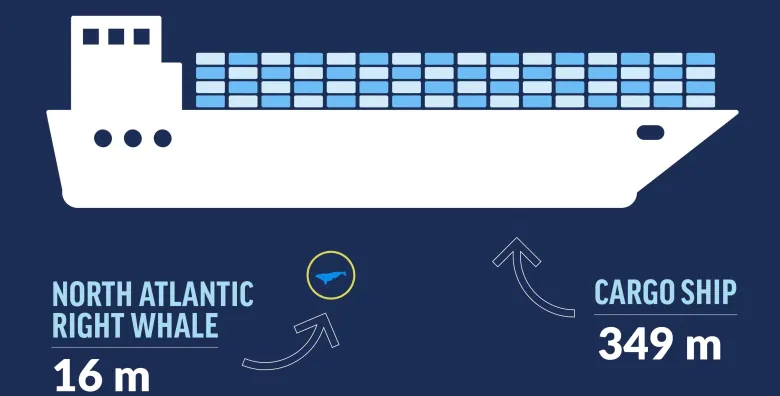

Current speed restrictions for ships moving through Canadian waters will not prevent North Atlantic right whales from being killed if struck, according to new research that also determined smaller vessels are capable of deadly impacts.

Sean Brillant, a conservation biologist for the Canadian Wildlife Federation and a co-author of the study out of Dalhousie University in Halifax, said researchers wanted to determine at what speed a ship has a high likelihood of killing a whale.

“Slowing big ships down does not reduce the death rate as much as we hoped it would,” said Brillant, adding that larger ships obeying current speed restrictions in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where many right whales feed in the summer, still have an 80 per cent chance of killing a whale if one is struck.

“Although the speed restrictions … are probably helping to reduce the chance of killing whales, it’s not going to solve the problem. It’s not enough.”

It’s estimated there are just over 350 right whales left in the world, but researchers say at least three new calves have been born in December.

Fishing gear entanglements and ship strikes are listed as the two most frequent causes of death for right whales. Between 2017 and 2020, there have been 45 observed right whale deaths in U.S. and Canadian waters, but scientists believe the actual number is likely much higher.

The size of the vessel, how fast it’s moving, the area of contact, how big the whale is and the thickness of its blubber and muscle layers are all factors in determining when a strike is fatal.

As an example, Brillant said a 45-tonne vessel travelling at 10 knots that hits a right whale in the middle of its body has roughly a 70 per cent chance of killing the whale. If it’s a 500-tonne vessel travelling at the same speed, the lethality rate rises to 80 per cent.

“Here’s a vessel complying with the speed restrictions, but we’re still at 80 per cent,” Brillant said.

The other big takeaway from the research is that relatively small ships, such as fishing boats or even racing vessels, can also kill these mammals. Brillant said the research was shared with fishermen, who were surprised by the findings.

“These vessels can’t get just kind of a free pass and we assume that they’re harmless,” he said. “People who are skippers of these vessels need to know that they can damage whales and, of course, be on the lookout and look for opportunities to avoid that.”

Brillant said he and his co-authors, Dan Kelley, a physical oceanographer at Dalhousie; and former student James Vlasic, also shared their findings with government officials and shipping companies.

The research was incorporated into Transport Canada’s marine management efforts this past summer.

“This data helped inform the decision to expand the application of the North Atlantic right whale vessel management measures to all vessels over 13 metres,” said Sau Sau Liu, a spokesperson for the federal department.

Previously, the restrictions only applied to vessels over 20 metres.

Additional measures taken by Transport Canada in 2020 included two speed-restricted seasonal management areas, a trial voluntary speed limit of 10 knots in the Cabot Strait, and a restricted area in the Shediac Valley between eastern New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Vessels were asked to avoid that area or slow their speed to eight knots.

“By using all scientific data available, the measures are continually being re-evaluated and reassessed for their effectiveness,” Liu said.

Transport Canada will engage stakeholders in reviewing the 2020 measures to inform any modifications for 2021.

As of mid-December, there had been just one confirmed right whale death recorded in 2020 — a calf killed in U.S. waters. No ship strikes or entanglements had been reported in Canadian waters.

The three new calves born this month and spotted in waters off the southern U.S. are giving hope to observers wishing for a “robust calving year,” said Philip Hamilton, a marine biologist with the New England Aquarium in Boston.

We have a first time mom! The first live right whale calf of the season was spotted by biologists with <a href=”https://twitter.com/CMAquarium?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>@CMAquarium</a> off Cumberland Island, GA December 4. Mom is known right whale ‘Chiminea.’ Chiminea is at least 13-years-old and this is her first known calf. Photo: <a href=”https://twitter.com/CMAquarium?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw”>@CMAquarium</a> <a href=”https://t.co/khcGrCSDOC”>pic.twitter.com/khcGrCSDOC</a>

—@NOAAFish_SERO

Calving season for the right whales usually runs from early December until the end of March, with a peak in early to mid-January.

Hamilton said the three mothers are whales who feed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the summer months — a good sign for how well the area is doing as a feeding ground for the species.

One calf was born to 13-year-old Chiminea, while another was born to 16-year-old Millipede. This is Millipede’s second calf. The third baby right whale was from an unnamed whale, tagged as 3942.

“Two of them are two mothers who have not given birth before,” Hamilton told CBC Radio’s Maritime Noon. “So they’re the hope for the future and we’re very excited about that.”