Dr. Lee Ju-hyung has largely avoided restaurants in recent months, but on the few occasions he’s dined out, he’s developed a strange, if sensible, habit: whipping out a small anemometer to check the airflow.

It’s a precaution he has been taking since a June experiment when he and colleagues recreated the conditions at a restaurant in Jeonju, a city in the southwest of South Korea, where diners contracted COVID-19 from an out-of-town visitor. Among them was a high school student who was infected with the coronavirus after five minutes of exposure from more than 20 feet away.

The results of the study, for which Lee and other epidemiologists enlisted the help of an engineer who specializes in aerodynamics, were published last week in the Journal of Korean Medical Science. The conclusions raised concerns that the widely accepted standard of six feet of social distance may not be far enough to keep people safe.

The study — adding to a growing body of evidence on airborne transmission of the virus — highlighted how South Korea’s meticulous and often invasive contact tracing regime has enabled researchers to closely track how the virus moves through populations.

“In this outbreak, the distances between infector and infected persons were….farther than the generally accepted 2 meter [6.6 foot] droplet transmission range,” the study’s authors wrote. “The guidelines on quarantine and epidemiological investigation must be updated to reflect these factors for control and prevention of COVID-19.”

People wearing face masks walk under a banner emphasizing an enhanced social distancing campaign in front of Seoul City Hall. The banner reads: “We have to stop before COVID-19 stops everything.”

(Ahn Young-joon / Associated Press)

KJ Seung, an infectious disease expert and chief of strategy and policy for the nonprofit Partners in Health’s Massachusetts COVID response, said the study was a reminder of the risk of indoor transmission as many nations hunker down for the winter. The official definition of a “close contact” — 15 minutes, within six feet — isn’t foolproof.

In his work on Massachusetts’ contact tracing program, he said, business owners and school administrators have fixated on the “close contact” standard, thinking just 14 minutes of exposure, or spending hours in the same room at a distance farther than six feet, is safe.

“There’s a real misconception about this in the public.” said Seung, who was not involved in the South Korea study. “They’re thinking, if I’m not a close contact, I will magically be protected.”

Seung said the study pointed to the need for contact tracers around the world to broaden the net in looking for people who had potentially been infected and to alert people at lower risk that they may have been exposed.

Linsey Marr, a civil and environmental engineering professor at Virginia Tech who studies the transmission of viruses in the air, said the five-minute window in which the student, identified in the study as “A,” was infected was notable because the droplet was large enough to carry a viral load, but small enough to travel 20 feet through the air.

“‘A’ had to get a large dose in just five minutes, provided by larger aerosols probably about 50 microns,” she said. “Large aerosols or small droplets overlapping in that gray area can transmit disease further than one or two meters [3.3 to 6.6 feet] if you have strong airflow.”

The South Korean study began with a mystery. When a high school senior in Jeonju tested positive for the coronavirus on June 17, epidemiologists were stumped because the city hadn’t had a COVID-19 case in two months. North Jeolla province, where Jeonju is located, hadn’t had one for a month. The girl hadn’t traveled out of the region in recent weeks, and had largely gone from home to school and back.

Contact tracers turned to the country’s Epidemic Investigation Support System, a digital platform introduced in South Korea amid the pandemic that allows investigators to access cellphone location information and credit card data of infected individuals in as little as 10 minutes.

Cellphone GPS data revealed that the student had briefly overlapped with another known coronavirus patient from a different city and province altogether, a door-to-door saleswoman who had visited Jeonju. Their connection was a first-floor restaurant on the afternoon of June 12 — for just five minutes.

Authorities in the city of Daejeon, where the door-to-door saleswoman was visiting from, said the woman did not tell contact tracers she’d visited Jeonju, about an hour’s drive away, where her company held a meeting with 80 people on the sixth floor of the building with the restaurant.

Lee, a professor at the Jeonbuk National University Medical School who has also been helping local authorities carry out epidemiological investigations, went to the restaurant and was surprised by how far the two had been sitting. CCTV footage showed the two never spoke, or touched any surfaces in common — door handles, cups or cutlery. From the sway of a light fixture, he could tell the air conditioning unit in the ceiling was on at the time.

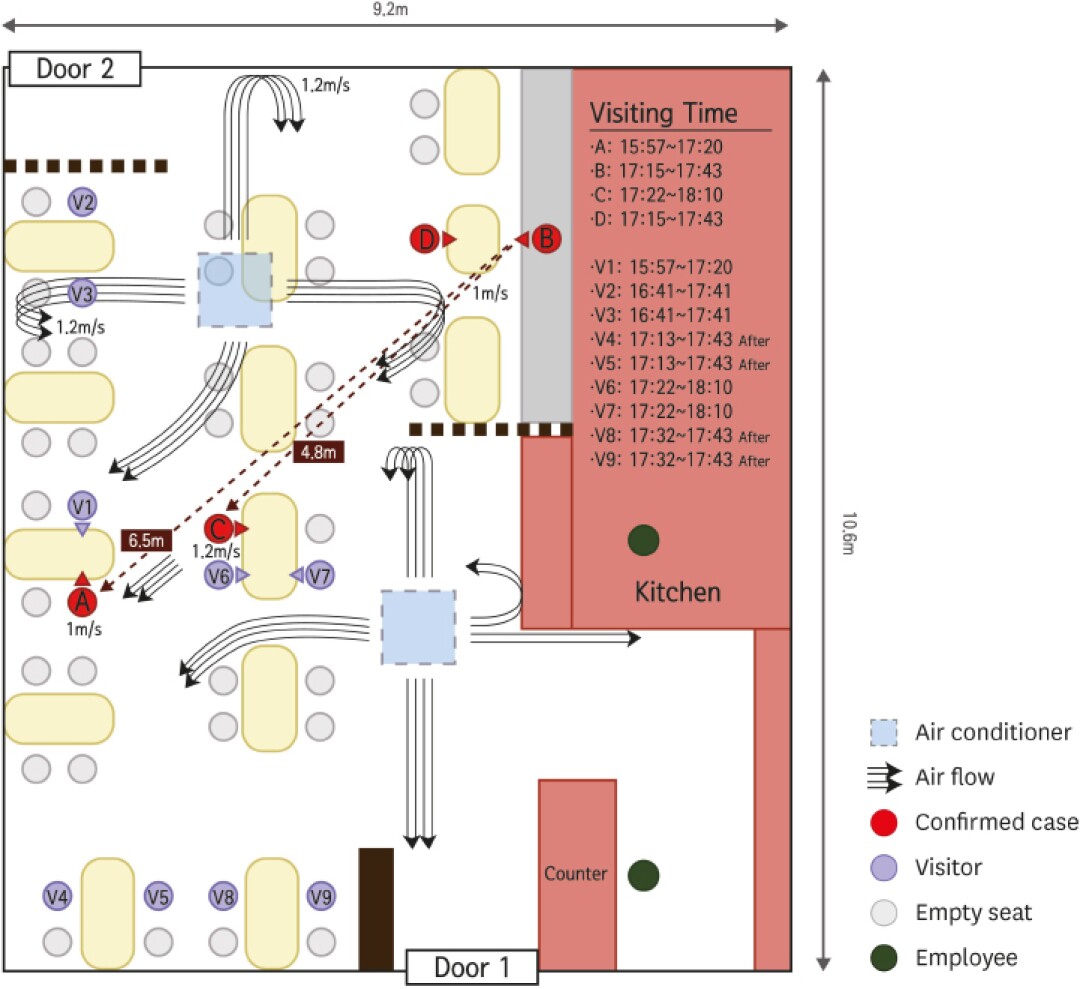

Diagram of the outbreak at a South Korean restaurant equipped with ceiling-type air conditioners: arrows represent the air flow. Curved air streamlines represent where air is reflected off a wall or barrier, and moves downward toward the floor.

(Korean Academy of Medical Sciences)

Lee and his team recreated the conditions in the restaurant — researchers sat at tables as stand-ins — and measured the airflow. The high school student and a third diner who was infected had been sitting directly along the flow of air from an air conditioner; other diners who had their back to the airflow were not infected. Through genome sequencing, the team confirmed the three patients’ virus genomic types matched.

“Incredibly, despite sitting a far distance away, the airflow came down the wall and created a valley of wind. People who were along that line were infected,” Lee said. “We concluded this was a droplet transmission, and beyond two meters.”

The pattern of infection in the restaurant showed it was transmission through droplets landing on the face rather than from aerosols, which are breathed in, said Marr, the Virginia Tech professor who was not involved in the study. The measured air velocity in the restaurant, which did not have windows or a ventilation system, was about a meter per second, the equivalent of a blowing fan.

“Eating indoors at a restaurant is one of the riskiest things you can do in a pandemic,” she said. “Even if there is distancing, as this shows and other studies show, the distancing is not enough.”

The study was published at a time when South Korea, like many other countries, is on edge amid a new wave of COVID-19 infections, with daily case rates hovering around 600 in recent days. Seoul, the capital, this week began requiring restaurants to close by 9 p.m., limiting coffee shops to take-out only and forcing clubs and karaokes to shut down.

The research echoed the findings of a July study out of Guangzhou, China, which looked at infections among three families who dined at a restaurant along the flow of air conditioning in tables that were three feet apart, overlapping for about an hour. Ten of the diners tested positive for the coronavirus. Contact tracers in South Korea similarly mapped out a large outbreak at a Starbucks in Paju in August, when 27 people were infected by a woman sitting under a second-floor ceiling air conditioning unit.

Seung, of Partners in Health, said by retracing infection routes epidemiological investigators in South Korea had helped researchers worldwide better understand the coronavirus’ spread.

“I showed it to my team doing contact tracing in Massachusetts, and their jaws are dropping,” Seung said. “We know how hard it is to do something like that — it’s impressive.”