For weeks, as the stock market regularly climbed to records, investors wondered what it would take to snap Wall Street out of its blissful state. The resurgent pandemic certainly wasn’t doing it. Even an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol wasn’t alarming enough to end the rally.

GameStop, though?

On Friday, the S&P 500 fell more than 1.9 percent, capping a stretch of volatile trading that left the index down more than 3 percent for the week — its worst week since late October.

By: Ella Koeze·Data delayed at least 15 minutes·Source: FactSet

The selling came as Wall Street was consumed by the antics of a group of day traders who have been bidding up a handful of stocks — notably the ailing video game retailer GameStop — and forcing losses on big hedge funds.

The traders appear to be mostly small investors who are focused only on a handful of stocks. But they have emerged as a new risk factor for large firms that had bet against those companies with what are known as short sales. Short sellers lose money when a company’s shares rise, and the losses are potentially limitless.

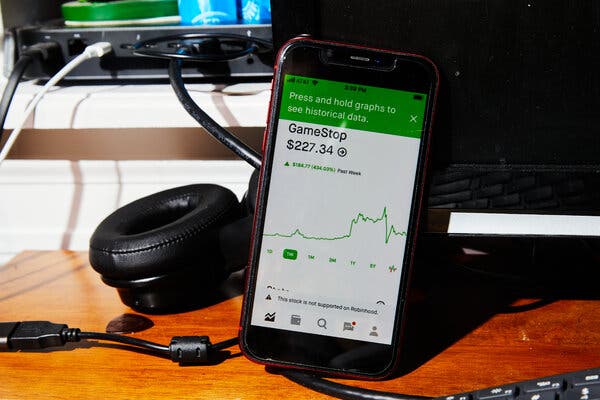

GameStop’s shares gained 400 percent this week and 1,600 percent this month. Short sellers who had bet against the stock are facing losses of as much as $19 billion in January, according to estimates from Ortex, a market data firm. Another target, AMC Entertainment, has gained 280 percent this week.

For the rest of Wall Street, the worry is that the hedge funds will have to sell shares of other companies to cover their losses on GameStop and AMC — “forced liquidation.” That selling was a factor in the stock market’s 2.6 percent drop on Wednesday, the S&P 500’s worst daily decline in three months, Mark Haefele, the chief investment officer at UBS Global Wealth Management, wrote in a note to clients on Friday.

It isn’t just GameStop that’s giving investors a reason to sell. They’re also concerned about the rollout of the coronavirus vaccine as countries begin to clamp down on supplies or warn of shortages. On Friday, the European Union announced plans to effectively halt any attempt by AstraZeneca to move vaccine doses manufactured in the bloc to other countries unless it first meets its supply obligations to the bloc’s 27 member states. Earlier in the week, Spain said it would have to partly suspend immunizations for lack of doses.

The trading Friday reflected some of these concerns. Shares of companies that are sensitive to concerns about the pandemic — Norwegian Cruise Line, Delta Air Lines and the shopping mall owner Kimco Realty — were all among the worst performers on the S&P 500.

But the conversation of the week focused on GameStop. And although the Securities and Exchange Commission and several lawmakers have said they’re watching the situation, it’s not yet clear how it will be addressed.

“The battle over GameStop is far from over, but there have been huge casualties,” Edward Moya, a senior market analyst at the trading firm OANDA, wrote in a note to clients on Friday. “A solution for this entire market dislocation will take time, and that could suggest this insane trading will continue a little while longer.”

The new focus on the market’s disconnect from fundamentals has come after stocks rallied more than 16 percent in 2020 despite the decimation of the economy and the human toll of the coronavirus pandemic. Many investors were already starting to raise concerns about the potential that financial markets had risen far too quickly after the Federal Reserve and lawmakers in Washington took unprecedented steps to shore up the economy and financial markets and as investors anticipated even more spending under a unified Democratic government.

To some investors, the week’s turmoil served only as a distraction from those positives. Even as stocks fell this week, several large companies, including Microsoft, Apple and Facebook, reported profit and sales growth. The selling Friday came even after Johnson & Johnson said that its one-dose coronavirus vaccine provided strong protection against Covid-19.

Mr. Haefele of UBS said he expected the “attention will likely shift back to earnings, stimulus, and the vaccine rollout,” and that when it does, stock markets will return to their gains.

The federal occupational safety agency on Friday posted new guidance for employers on reducing the spread of Covid-19 in the workplace, just over one week after President Biden signed an executive order directing it to do so.

The move by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, part of the Labor Department, includes only recommendations, not requirements. But the agency said it was exploring a rule mandating certain protective measures.

The agency declined to issue such a rule, known as an emergency temporary standard, during the Trump administration. But Mr. Biden indicated support for a standard during the campaign.

The new guidance makes fewer distinctions than the Trump administration’s version based on the exposure risk of different workers. “Everyone should be protected, not some more protected than others,” Ann Rosenthal, a senior adviser to the agency, said on a video call with reporters.

The document issued on Friday also uses less equivocal language than the agency did under President Donald J. Trump. For example, it says the most effective prevention programs “ensure that absence policies are nonpunitive.” During the Trump administration, the agency advised employers to “ensure that sick leave policies are flexible and consistent with public health guidance.”

Meatpacking and meat processing have been a particular source of concern, accounting for an outsized portion of Covid-19 infections nationally.

In late December, a state judge in California issued a temporary restraining order in a lawsuit involving workers at a local poultry plant, requiring a variety of safety protocols such as providing masks and requiring workers to wear them, as well as face shields, where social distancing isn’t possible.

The court announced Friday that it would issue a preliminary injunction to the same effect, giving workers an ongoing ability to force compliance if the company backs off the protocols. It cited evidence submitted by the plaintiffs that “regulatory agencies are overwhelmed by the issues raised by the Covid-19 pandemic and are unable to inspect with the same regularity as was the practice prior to the pandemic.”

Robinhood raised $1 billion from investors on Thursday to help it cover cash demands during the week’s stock trading frenzy. But the online brokerage, the venue of choice for small investors during the mania for shares in GameStop, AMC Entertainment and others, must still confront feelings of betrayal from its loyal customers and questions about its business model, the DealBook newsletter writes.

In imposing trading limits on hugely popular stocks yesterday because of financial requirements from a central Wall Street trading hub, Robinhood alienated some of its core customers. (Small groups of them gathered to protest outside the New York Stock Exchange and Robinhood’s headquarters in Menlo Park, Calif.) That sense of abandonment — that the brokerage had chosen to protect Wall Street institutions at risk of losing money over small investors making it — may be harder to address than annoyance over technical outages, like those that bedeviled the platform last year.

Meanwhile, Robinhood’s business model of no-fee trading is under renewed pressure. The company turned to existing investors and bank credit lines for cash because it cannot raise money by charging customers more. It benefits from more trading — but more trading also means it needs more capital to hold against its users’ trades, especially when volatility makes its partners in settling trades more risk averse. Becoming a publicly listed company, able to more easily sell stock and raise debt, would help, but future trading frenzies could lead to more demands for cash.

Washington also sees cause for concern. The Securities and Exchange Commission said on Friday that it would review action that “may disadvantage investors or otherwise unduly inhibit their ability to trade certain securities.”

Lawmakers in the House and Senate have pledged to hold hearings into the inner plumbing of Wall Street trading, and could perhaps require brokerages to post higher margin requirements to prevent similar runs. That could make trading costlier for users, turning some off to the whole business.

GameStop shares surged on Friday, the latest turn in a week of wild price swings in companies that have been bid up in a frenzy of activity by small investors.

This week, shares in GameStop — a stock Wall Street had given up on — have reached as high as $483 and fallen as low as $61.

GameStop had ended the regular trading session down 44 percent on Thursday. The drop earlier in the day had come as Robinhood and other trading platforms said they would limit the ability to buy certain securities, including AMC Entertainment and BlackBerry.

Then the trading app reversed some of the restrictions. The shares rose about 65 percent on Friday.

“We plan to allow limited buys of these securities” starting Friday, Robinhood said in blog post on Thursday afternoon. “We’ll continue to monitor the situation and may make adjustments as needed.”

Robinhood called its move “a risk-management decision,” and later said it had raised $1 billion to cover the costs of the high volume of transactions so it wouldn’t need to reimpose restrictions.

Other brokerage firms have also limited trading of some of the same stocks. The Securities and Exchange Commission said Wednesday it was “actively monitoring” the volatile trading.

Other stocks spurred on by day traders in Reddit forums like “Wall Street Bets” include AMC Entertainment, the movie-theater chain that has narrowly avoided bankruptcy four times in the past nine months, which rose 53 percent on Friday after dropping 57 percent on Thursday.

Robinhood curbed trading in cryptocurrencies on Friday, its latest restriction on users in a frenzied week of trading centered on the soaring stock of the video game retailer GameStop.

The trading platform said that instant deposits were temporarily unavailable for crypto purchases, which means users cannot buy anything until their deposit settles. But customers can still use any settled funds in their account to buy cryptocurrencies.

“Due to extraordinary market conditions, we’ve temporarily turned off instant buying power for crypto,” Robinhood said in a statement. “We’ll keep monitoring market conditions and communicating with our customers.”

A spokeswoman for the firm said it typically aims to give customers immediate access to up to $1,000 of their deposit. The new rules do not affect its Gold customers.

Robinhood and several other online brokerages put restrictions on trading of stocks like GameStop and the movie theater chain AMC, which soared this week in a rally sparked by amateur investors. But the platform said that it was beginning to relax some of those limitations.

Robinhood is now allowing its users to buy shares in some of the affected stocks, but within certain limits: Users can buy just five shares of GameStop, according to its website, and up to 115 shares of AMC. Positions in options contracts are also limited.

GameStop started the week as a curiosity — an illustration of how markets may have become detached from reality and how small traders can use options to drive stock prices.

By Tuesday, the story of the stock had become an obsession, as it nearly doubled in price. Groups of renegade investors on forums such as Reddit and Discord were trying to force a short squeeze — pushing up the price of stocks that hedge funds had bet would go down.

On Wednesday, GameStop was the most actively traded stock, with $24 billion worth of shares switching hands as prices rose 135 percent. Brokerages started to worry about their exposure, with some limiting customers from purchasing shares on margin — with borrowed funds. Elon Musk and Chamath Palihapitiya jumped into the fray, urging the crowd on via Twitter. The Securities and Exchange Commission said it was “actively monitoring the ongoing market volatility.”

The surge of GameStop and other stocks — AMC Entertainment and American Airlines were two other favorite targets — was starting to take a toll on hedge funds. Melvin Capital had to raise a $2.75 billion bailout from Citadel and Point72 early in the week, and its founder, Gabriel Plotkin, confirmed to CNBC that he was throwing in the towel and had exited his position.

Point72’s returns were down nearly 15 percent for the year as of Wednesday, and returns at Citadel were down by single digits.

The stock had its first daily drop of the week on Thursday, as the apps that many traders relied on limited action. Robinhood, among others, temporarily prevented its users from buying new positions in GameStop and other companies. The announcement infuriated users, who felt that the platform had betrayed them to satisfy big investors. “They call themselves Robinhood, but they’re helping the wealthy take money back from the middle class,” said a protester outside Robinhood’s headquarters.

Robinhood said it would reallow some trades on Friday, potentially setting up another day of wild swings. It said it had placed the limits because of “financial requirements” and was raising an infusion of $1 billion to ensure it wouldn’t need to further limit transactions.

Analysts expect GameStop to report a loss from continuing operations of $465 million for 2020, on top of the $795 million it lost in 2019.

Chevron reported its third straight quarterly loss on Friday, as oil and natural gas prices remained low because the pandemic has disrupted activity across the economy. It was the company’s worst performance in four years.

The oil industry has suffered mightily over the last year, forcing companies to slash jobs, write off assets and, in the case of dozens of mostly smaller firms, file for bankruptcy.

With its varied international operations, Chevron comes out of the year stronger than most of its competitors, but the California-based company still lost $665 million in the last three months of 2020. The company lost $5.5 billion for the full year, down from a $2.9 billion profit in 2019.

“2020 was a year like no other,” said Chevron’s chief executive Mike Wirth in a statement. “We were well positioned when the pandemic and economic crisis hit, and we exited the year with a strong balance sheet.”

With oil and gas prices rising at the end of the year, Chevron’s oil and gas production yielded a $501 million profit in the fourth quarter, but its refining and chemical businesses continued to suffer as the global economy remained sluggish.

The president of Germany’s financial oversight authority is stepping down and the body will be reorganized following the collapse of the financial technology company Wirecard and the ensuing accounting scandal, the German finance minister, Olaf Scholz, said on Friday.

Mr. Scholz said the regulatory agency, known as BaFin, needed a reorganization to more effectively carry out its duties. The announcement came following a monthslong investigation into Wirecard’s collapse in June.

“Alongside of the planned organizational reform at BaFin, there should also be a change in personnel,” Mr. Scholz said in a statement announcing the departure of Felix Hufeld, who had served as president of BaFin for six years.

German authorities have been criticized for failing to act despite reports of irregularities at the Bavaria-based Wirecard, which filed for insolvency proceedings in June. Days earlier, the company acknowledged that 1.9 billion euros ($2.1 billion at the time) on its balance sheets probably never existed. The episode marked a dramatic turn of events for Wirecard, an electronics payments processor that had once been listed on Germany’s blue-chip DAX stock index.

Calls for Mr. Hufeld to be replaced came after BaFin reported one of its employees to state prosecutors on Thursday on suspicion of insider trading linked to Wirecard shortly before it collapsed.

Munich prosecutors are investigating Markus Braun, Wirecard’s longtime chief executive, and Jan Marsalek, an Austrian who fled Germany and remains at large. German prosecutors believe Mr. Marsalek may have embezzled more than €500 million.

transcript

transcript

Benefits of Acting Now on Relief ‘Far Outweigh the Costs,’ Yellen Says

Speaking alongside President Biden, Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen pushed for swift action on coronavirus relief legislation to combat the economic impacts of the pandemic.

-

“Millions of people are out of work, unemployed. The future of millions are held back for no good reason other than our failure to act. So the choice couldn’t be clearer. We have learned from past crises the risk is not doing too much. The risk is not doing enough. And this is the time to act now. I’ve asked Secretary Yellen, who’s been leading this effort to come in, and we’re going to go into some detail among ourselves. But I think she has a statement to make as well.” “Thank you for the privilege, Mr. President. Well, there is a huge amount of pain in our economy right now, and it was evident in the data released yesterday. Over a million people applied for unemployment insurance last week, and that’s far more than in the worst week of the Great Recession. And economists agree that if there’s not more help, many more people will lose their small businesses, the roofs over their heads and the ability to feed their families. And we need to help those people before the virus is brought under control. The president’s American rescue plan will help millions of people make it to the other side of this pandemic. And it will also make some smart investments to get our economy back on track. I want to emphasize, the president is absolutely right. The price of doing nothing is much higher than the price of doing something and doing something big. We need to act now. And the benefits of acting now, and acting big, will far outweigh the costs in the long run.”

President Biden received his first formal economic briefing from Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen on Friday as the White House pushes to get another stimulus package moving through Congress.

The meeting took place in the Oval Office and Vice President Kamala Harris was also in attendance. Ms. Yellen was sworn in on Tuesday and has spent her initial days in the job getting briefed by advisers on the status of the existing stimulus programs and speaking to foreign finance ministers about America’s plans to engage with its allies. She has also been monitoring the unusual stock market activity related to GameStop this week.

“The price of doing nothing is much higher than the price of doing something and doing something big,” Ms. Yellen said before the briefing. “We need to act now. The benefits of acting now and acting big will far outweigh the costs in the long run.”

Ms. Yellen was joined in the meeting by Brian Deese, director of the National Economic Council, and Jared Bernstein of the Council of Economic Advisers.

The economic recovery shows signs of slowing, fueling concerns among White House officials that time is running short to pass a robust package before some emergency benefits expire in March. Democrats in Congress are still debating whether to push legislation forward on their own, using a mechanism called reconciliation, or work with Republicans on a bipartisan bill.

Ms. Yellen foreshadowed her advice to Mr. Biden during her confirmation hearing last week. She called on lawmakers to “act big” and said that providing robust support was the fiscally responsible thing to do to avoid long term damage to the economy.

Ms. Yellen’s team at Treasury is still taking shape and people close to her suggest that she will most likely assume the role of offering the White House high-level economic advice and helping to close the deal with lawmakers in Congress, rather than directly engaging in negotiations. The Treasury Department will also be heavily involved in the design and implementation of the relief programs.

Mr. Biden indicated that passing relief legislation was his top priority.

“People are going to be badly, badly hurt if we don’t pass this package,” Mr. Biden said on Friday.

Severe recessions in Germany and France last year, caused by the coronavirus pandemic, began to improve slightly toward the end of 2020, as a second series of lockdowns had a milder impact on their economies, those governments reported on Friday.

But prospects for a hoped-for recovery this year in Europe’s two largest economies may be delayed as a new variant of the virus circulates and as problems emerge in the rollout of vaccines, economists warned.

The French economy shrank by 8.3 percent last year as two sets of national lockdowns, lasting months, dealt strong blows to business activity, the national statistics agency reported on Friday.

But the overall contraction was less than expected. By reducing the strictness of the nation’s second lockdown, which went into effect in October and was mainly limited to restaurants and cultural events, the government avoided a worse economic hit, the statistics agency said. Growth in the fourth quarter fell 1.3 percent, compared with the same period a year ago — far less than the 4 percent contraction forecast by many economists.

In a note to clients, the Dutch bank ING wrote, “The big question now is whether France will manage to avoid a second recession in 15 months.”

“Given the current health situation, another recession looks all but certain,” the bank added.

The economy in Germany grew 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter compared with the third quarter, the country’s Federal Statistical Office said. That compared to growth of 8.5 percent in the third quarter, as the economy bounced back from a severe downturn early in the year, when the pandemic brought German factories to a standstill.

Over all, the German economy shrank 5 percent for all of 2020, the statistical office said.

In a separate note to clients, ING said, “It’s the worst performance since the financial crisis in 2009 but still much better than some had feared at the start of the Covid-19 crisis.”

Economists predict that the German economy will shrink again in the first quarter of 2021 (not the first quarter of 2020 as was earlier reported here) because of the slow rollout of vaccines and extended lockdowns.

American Airlines appeared to seize an opportunity on Friday morning when it announced plans to raise more than $1.1 billion by selling shares amid a frenzy for its stock.

The airline this week found itself in the middle of a war of wills between amateur individual investors and professional traders at hedge funds and financial firms. The individual investors, who congregated on social media sites like Reddit, collectively bought up shares of companies like GameStop and AMC Entertainment that professionals had bet against. In so doing, some of these self-described financial insurgents earned big profits and forced some big investors to take major losses.

Emboldened by that success, the amateurs turned their attention to other companies whose stocks have been shorted, or bet against, including American. The airline said on Thursday that it lost nearly $9 billion last year, a figure that was largely ignored by the small-scale investors who tried to pile into its stock, despite being hamstrung by brokerage firms like Robinhood that restricted trading in several stocks, including American’s. The company’s stock rose more than 20 percent between Wednesday and Friday morning, but fell 5 percent on Friday.

By issuing additional shares, American seems be making the most of the thirst for its stock while it can. There is no guarantee that interest will persist because online traders could easily decide to move onto other companies.

“American will need to shift its focus to fixing the balance sheet after demand comes back and the company begins generating cash again,” Helane Becker, managing director and senior airline analyst at Cowen, an investment bank, said in a note to clients on Thursday.

Airlines have been burning through cash since the pandemic took hold early last year. Air travel has recovered somewhat, but passenger traffic is still down about two-thirds compared with the same time in 2019.

American entered the pandemic with more debt than its rivals. As a result, professional investors have bet heavily against it. According to S3 Partners, a financial data firm, American is the most shorted major U.S. airline, with nearly 19 percent of its shares subject to short trades, compared to just 4.7 percent for JetBlue and 4.4 percent for United Airlines.

HNA Group, a Chinese conglomerate that spent $50 billion on trophy businesses spanning the globe but has since grappled with high debt, said on Friday that a creditor has filed a petition for it to be declared bankrupt.

HNA said in a short statement that the creditor submitted the application to a court in the southern province of Hainan, where HNA is based, because the company had failed to pay its debts. The company did not say whether the court had ruled on the petition.

The announcement highlights challenges that continue to besiege the once high-flying company, which previously owned big stakes in Deutsche Bank, Hilton Hotels and Virgin Australia. HNA asked the Chinese government to help bail it out last year, blaming the impact of the coronavirus on flight cancellations for its debt woes.

Founded as a regional airline, HNA was once a rising star among a new breed of Chinese companies that included Anbang Insurance Group, Dalian Wanda and Fosun International. Lubricated by cheap loans from state-run banks and aided by strong political connections, these private companies scoured the world for splashy deals, buying hotels, production companies and even stakes in big global banks.

But as these companies expanded their empires, authorities worried that the huge debt bill they had racked up posed a lurking risk to China’s financial system.

Struggling under a massive $90 billion debt bill, HNA sold off billions of dollars’ worth of properties. At one point it was so strapped for cash that it asked its own employees to lend it money.

Eventually, HNA’s chairman admitted that the company was having trouble paying its bills and the salaries of some employees. Officials from the civil aviation administrator and China Development Bank stepped in last year to take over the responsibility of managing the company’s risk. HNA also gave two board seats to local government officials.

HNA said on Friday that it had been notified by a court in Hainan, where it is headquartered, that creditors applied for its bankruptcy. The company would cooperate with the court, it said in a statement on its website.

The economic upheaval caused by the pandemic is changing communities across the country. Hundreds of thousands of businesses have closed, leading to lost livelihoods and empty storefronts. Many of these businesses were neighborhood pillars, beloved locales that we returned to over and over again. In your neighborhood, perhaps the bar where you met friends after work, the restaurant where your family celebrated birthdays or the bookstore where you loved to browse is now gone.

The New York Times would like to hear from you about a local business that has shut down. Why was it special to you, and what do you miss about it? How is its absence altering the fabric of your community?

We may contact you with a few follow-up questions. And if you can, please share a photo of the business as well.