Sitanan Satsaksit kneeled outside her brother’s apartment building, her eyes lowered in prayer beneath a wide-brimmed hat. As she tried to reconstruct the events of that evening six months earlier, she heard his distressed voice in her head.

They had been chatting on the phone, she back in their native Thailand and he in his adopted home of Cambodia. An outspoken democracy activist and satirist, 38-year-old Wanchalearm Satsaksit was among more than 100 Thai dissidents who had fled into exile following a 2014 military coup.

He told her he was buying meatballs outside his high-rise in Phnom Penh, the capital, when she heard a commotion, a series of bangs and shouts. Then came his plaintive cry, repeated again and again: “I can’t breathe.”

They were his last words before the line went dead.

Witnesses told local journalists they saw Cambodian-speaking men bundle the slight, bespectacled Wanchalearm into a dark blue Toyota Highlander and drive off along the riverside road. But authorities in Cambodia and Thailand have reported no progress in the investigation.

Human rights groups believe his kidnapping was part of a pattern of politically motivated disappearances in Southeast Asia, where authoritarian governments have often helped one another target dissidents in exile.

And so Sitanan found herself on a street corner outside the Mekong Gardens apartment building in early December, holding a basket of offerings as a trio of Buddhist monks scattered sacred water and prayed for Wanchalearm. She had traveled to Phnom Penh to conduct her own investigation, meet with her brother’s associates, press police for answers and testify before a judge in a desperate and lonely search for justice.

“I was waiting for this opportunity for six months,” she said. “So as difficult as it was, it was also a relief, and happiness, to come to Phnom Penh.”

Sitanan Satsaksit hands an offering to a monk during a Buddhist ceremony at the site of her brother Wanchalearm’s disappearance.

(Chor Sokunthea / AFP/Getty Images)

The abduction has taken on added significance amid seismic political events in Thailand this year. Pro-democracy protests have called not only for an end to the military-dominated government but also for limits on the powers of the monarchy, an astonishing display of defiance in a country where the king is supposed to be revered, and criticizing him is a criminal offense.

A popular activist who campaigned for gender and LGBTQ rights with sharp and sometimes bawdy humor, Wanchalearm joined the “red shirt” political movement allied with former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. After the military ousted Yingluck in 2014, the junta issued a warrant for Wanchalearm’s arrest.

He fled to neighboring Cambodia, where for the next six years he continued to denounce the military online — most recently in a Facebook video mocking the former army chief and current prime minister, Prayuth Chan-ocha. It was posted June 3, the day before his abduction.

Throughout the summer and into the fall, demonstrators held up posters of Wanchalearm, making him a symbol of the military’s failure to ensure political rights. His name was spray-painted on Bangkok street corners and trended on social media, bringing the issue of missing dissidents into the national conversation for the first time.

Pro-democracy students hold posters of Wanchalearm Satsaksit during a protest outside Bangkok, Thailand, in August.

(Sakchai Lalit / Associated Press)

Since 2016, eight Thai activists have disappeared from exile in Laos or Vietnam. In December 2018, two were found floating in the Mekong River along the Laotian border, their faces mashed and bodies stuffed with concrete.

All were wanted in Thailand on criminal charges related to criticism of the government or monarchy. In each case, including Wanchalearm’s, Thai authorities have denied involvement.

“This is a spine-chilling message that there is no safe place for critics of the monarchy,” said Sunai Phasuk, a Bangkok-based researcher for Human Rights Watch. “Even those who escape from Thailand to other countries are still within the reach of brutal repression.”

But what was different about Wanchalearm’s abduction is it took place in broad daylight, in view of witnesses and security cameras, offering a sliver of hope that he could be found — or his captors brought to justice.

“Thailand has a very good operation with disappearances — you never find anything, anything at all,” said Pornpen Khongkachonkiet, who heads the Cross Cultural Foundation advocacy group and accompanied Sitanan to Cambodia. “This time, there is a lot of evidence if the authorities want to look at it.”

It remains unclear if they will.

The day after Wanchalearm went missing, a Cambodian police spokesman said he believed the reports to be “fake news.” Weeks later, the Cambodian government told a United Nations working group on enforced disappearances that it had no knowledge of the abduction and no record that Wanchalearm was even in the country.

Security camera footage shows an SUV leaving the spot where Thai activist Wanchalearm Satsaksit was abducted in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

(Cross Cultural Foundation)

In August, the government reported that the police investigation was coming up empty. Wanchalearm wasn’t listed as a resident at his apartment building, so authorities continued to question whether he’d lived there. The license plate of the Toyota SUV seen in security footage was missing from official records, and interviews with three people “confirmed that there were no reports of abduction in the said area.”

The Thai government maintained that it had no jurisdiction over the incident and would wait for Cambodia to finish its investigation. The U.N. working group said it was “alarmed” by Thailand’s position.

At her home in the northern Thai province of Ubon Ratchathani, Sitanan grew increasingly frustrated.

She had helped raise her brother, nine years her junior, although she avoided politics and had long pleaded with him to tone down his commentary. From time to time he’d send Sitanan pictures of men he believed were watching him in Phnom Penh.

In mid-May, police visited his mother at her rural home to discuss his activities, prompting him to curse the officers in his next video.

Yet he refused to seek asylum in the West like other prominent Thai dissidents, and seemed determined to make a life in Cambodia.

He launched a series of small businesses, including a stall selling Thai papaya salad, but each failed. At one point, he and Sitanan traveled to Africa in the hope of starting a commercial banana farm in Cambodia, but that fizzled too.

“He never knew about money,” Sitanan said. “He was always focused on activism.”

She hired a Cambodian lawyer to file a lawsuit in Phnom Penh, then pushed for the opportunity to submit evidence. In October, the judge issued her with a summons, and on Nov. 10, Sitanan, Pornpen and two Thai lawyers flew to Cambodia.

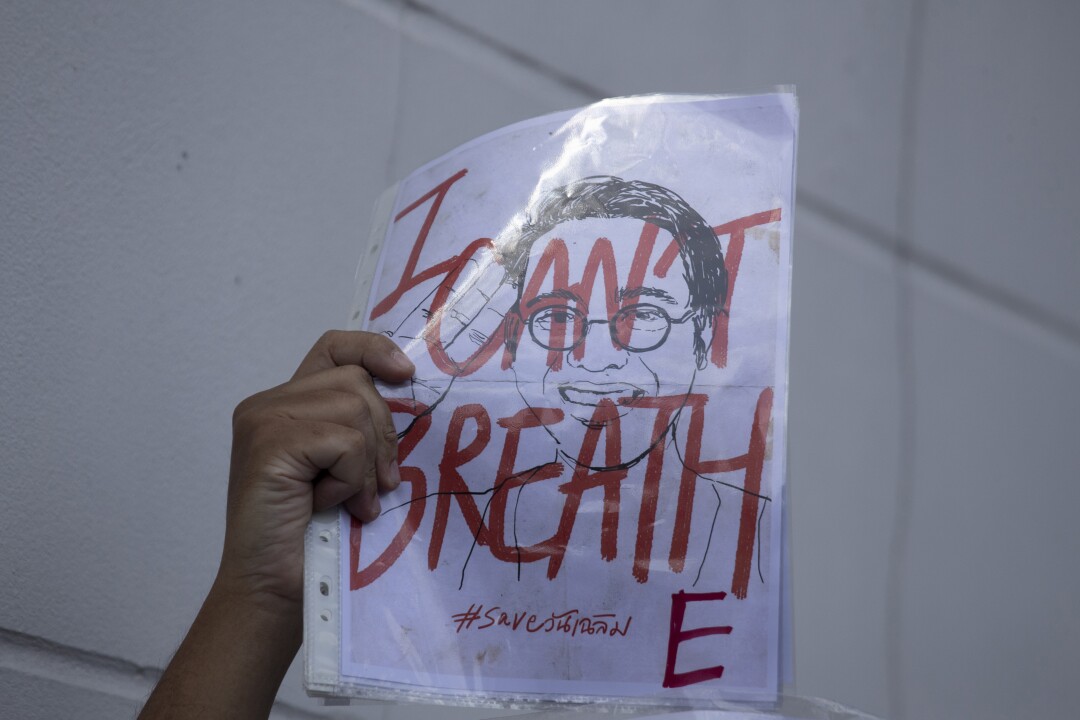

A Thai activist holds up a picture showing the last words activist Wanchalearm Satsaksit was heard speaking when he was kidnapped.

(Sakchai Lalit / Associated Press)

After two weeks in COVID-19 quarantine, the group hit the streets, hoping to collect more information to jump-start the case. They found that Thais who knew Wanchalearm were reluctant to meet in person, fearful for their safety. Police denied their request to enter his apartment. Witnesses refused to talk.

But the team managed to track down Wanchalearm’s roommate, a Cambodian who went by “Ricky,” who said he and Wanchalearm were both at home June 4. That morning, a pale-looking Wanchalearm turned to his roommate and said, without explanation: “Ricky, I am gonna die. I am gonna die.”

Pornpen, a veteran advocate in missing persons and torture cases, said their research made it clear that Wanchalearm was targeted for his political views.

“He had no other enemies, no one was after him in Cambodia,” she said. “He didn’t borrow money to go to the casinos. He had no personal conflict at all.”

Sitanan compiled the roommate’s account, Wanchalearm’s bank details, photographs and other documents demonstrating his presence in Cambodia into a 177-page dossier and carried it into the Phnom Penh Municipal Court on the morning of Dec. 8. For an hour and a half, Judge Sin Sovannroth heard her testimony and asked questions through her Cambodian lawyer and a translator.

Afterward, she told reporters that her evidence should be more than enough for the judge to forward the case to a trial court.

Sitanan Satsaksit arrives at Phnom Penh Municipal Court in Cambodia on Dec. 8.

(Heng Sinith / Associated Press)

In private, she was less confident. A day earlier she had met a senior police official involved in the case who said he had still seen no evidence that Wanchalearm was kidnapped.

“My conclusion was that these two institutions — the courts and the police — have still done almost nothing on the investigation,” she said.

Amnesty International sharply criticized Cambodian authorities for “glaring inadequacies” that raised doubts “about whether they are acting in good faith.” The government’s treatment of its own critics offers little hope that the inquiry will suddenly pick up steam.

Prime Minister Hun Sen, in power for 35 years, has locked up dozens of political prisoners and hounded opposition leaders with criminal charges. Last year, a Cambodian opposition politician living in Thailand was attacked with a stun gun in an attempted abduction in suburban Bangkok.

The Thai and Cambodian governments have also collaborated in the forcible return of exiled dissidents, in likely violation of international laws. In 2018 Thailand secretly extradited an exiled Cambodian, Rath Rott Mony, who served a two-year prison term for involvement in a documentary on child sex trafficking that angered Hun Sen’s government.

“We fear that the authoritarian governments of Southeast Asia are exchanging opposition activists with each other,” said Somchai Homlaor, one of the lawyers who traveled with Sitanan. “For Wanchalearm’s case I don’t think it’s an issue of capability in Cambodia, but of willingness to bring the perpetrators to justice.”

Back in Thailand, Sitanan said she would continue to press for justice, once she concludes another 14-day quarantine at the end of December.

“I don’t know what I will do next, except that I will keep going forward,” she said. “I will keep working to find the truth of what happened to my brother.”