Autumn’s blaze of glory, all flame-red leaves and burnt-gold foliage, offers an opportunity to marvel at the brilliance of the natural world before hunkering down for winter. Though, as nature goes into hibernation, forests, woods, parks and arboretums can often feel alive with walkers, joggers and families exploring them.

The experience of lockdown has changed many people’s relationships with nature and will undoubtedly extend our interaction with the arboreal beyond the traditional leaf-peeping season. Outdoor trends, such as forest bathing, awe-walks and even park strolls, have become a lifeline to many, and now the UK’s most spectacular spaces set aside for trees – arboretums – are seeing record numbers of visitors.

“The arboretum being shut for 10 weeks had a huge impact. More people have come than ever, even though we have capped the numbers. In August, we had 10,000 more day visitors than last August,” says Andrew Smith, director of Westonbirt Arboretum, near Tetbury, Gloucestershire.

-

Clockwise from above: Tony Kirkham of Kew Gardens: ‘If we can tell stories about trees, then trees will get the respect they deserve.’; Japanese maple leaves; one of the oldest specimens of Turner’s oak

Tony Kirkham, head of arboretum at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, describes arboretums as “a living reference library of trees”. At Kew there are more than 2,500 species from around the world, some of which are nearly 300 years old.

“The term arboretum became popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it’s slippery,” says Paul Elliott, professor of modern history at the University of Derby. “Arboretum meant tree collection, but it was more than just a group of trees of the same kind: it was a systematic collection that had botanical significance. However, in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, they became a bit of a joke. You’d see people in their small gardens having a few trees and labelling it an arboretum.”

There are no strict lower limits on what constitutes an arboretum and many are still in private hands. Elliott estimates there are more than 200 in England and Scotland, recorded on the National Heritage List for England and the Historic Environment Scotland inventory of gardens and designed landscapes (figures are not available for Wales and Northern Ireland). Many, such as at Westonbirt (known as the National Arboretum), started life as private collections by wealthy individuals.

“It was a craze for wealthy people with some land,” says Kirkham. “Lots of these people went for rarity, the new introductions. As they were being discovered, they wanted to be the first to have them in their collections.”

The first tree to be planted at Westonbirt was a Scots pine to mark the 21st birthday of Robert Stayner Holford, heir to one of the grandest estates in Britain, and founder of the arboretum in 1829. With serious tree planting beginning around 1852, thousands of trees from Asia and the Americas were planted in this part of Gloucestershire.

“If you look at maps of the time, they created an arboretum from nothing,” says Westonbirt archivist Alison Vry.

According to Derby University’s Elliott, “it was about showing off, they [wealthy land owners] collected these exotic trees and shrubs almost as if they were works of art”.

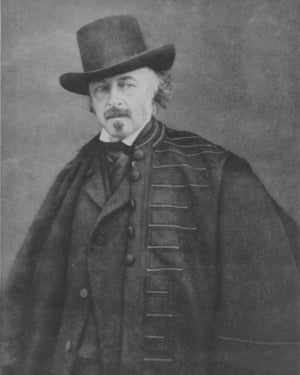

The man responsible for this craze among the upper classes, says Elliott, was John Claudius Loudon, a Scottish writer, landscape designer and “a key early proponent of the idea of arboretums as a public place”. Loudon was a prolific horticultural and landscape design writer, and he communicated many of his ideas through the Gardeners Magazine, which he started in 1826.

“He was very interested in transforming the urban environment by ‘greenifying’, or beautifying towns and cities, and bringing parks, gardens and green spaces to the masses,” says Elliott.

-

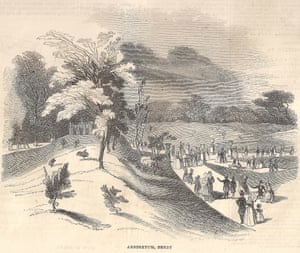

Scottish landscape designer John Claudius Loudon, and an illustration of Derby arboretum, which he worked on. Courtesy of Paul Elliott

Following the publication of his eight-volume Arboretum et fruticetum britannicum in 1838, Loudon was given the opportunity to put his “Gardenesque” theories of landscape design in public spaces into practice on land gifted to the people of Derby by textile merchant Joseph Strutt. Derby Arboretum opened in 1840 as what its current manager Mick McNaught describes as the “first purpose-built public park in Britain”.

Free to the public for two days a week at first, and with 1,013 species of individually labelled trees, McNaught says Derby Arboretum “was laid out as a scientific collection. Both Strutt and Loudon were committed to educating the working classes. It was all about trying to give a place of recreation and enjoyment, while at the same time offering an opportunity to improve their minds.”

Derby Arboretum was an instant success, and sparked a wave of park openings across an increasingly industrialised Britain. Elliott says that as a result, “arboretums were adopted as a model for public parks”.

“There was this idea that people would walk around the park and be learning botany and arboriculture, reading the guidebooks and observing how the trees were growing.”

McNaught says of Derby Arboretum that “even today, to the people who live around it, it’s their local park, but it’s of national importance”.

The connection between public education and recreation was always part of the plan for Derby Arboretum. But even trees planted centuries ago as private collections have since come into the public domain. Princess Augusta’s extensions to Kew Gardens in 1759 are today seen by two million visitors a year. Similarly, Westonbirt opened to the public when management of the park was passed to what is now Forestry England in 1956.

Kirkham explains that “a big role for an arboretum is education, because schools can come in with a teacher and do every part of the national curriculum. Maths by measuring trees, working out circumference and volume. History and geography – the year they were introduced and where from. They are an amazing educational resource.”

And it is a resource that’s becoming important in terms of conservation and climate crisis. “Our collection also provides a place to study how a changing climate is affecting a variety of tree species,” says Westonbirt’s Smith.

Kirkham adds: “We are looking into building a more resilient landscape [on a global scale]. Tree selection in the next 10 years is going to be critical if we are to keep a treescape. Using collections in arboretums in the UK and around the world is going to be an important resource”.

A walk around Derby, Kew, Westonbirt or any of the other UK’s arboretums on an autumn day demonstrates that whatever their histories, they are a much-loved part of the landscape. They also have an important role to play in our future health.

“It’s been proven that trees are good for your mental wellbeing,” says Kirkham. “They have shown that sick people get better quicker if they can see trees from their hospital window. An arboretum that people can walk round, looking at seasonal attributes should be highly valued.”

He adds: “I think if we can draw people into an arboretum and tell them stories about trees, then trees will get the respect that they deserve”.