Growing up in a small west Lancashire town surrounded by potato and cabbage fields, I always felt the mountains were a long way away. They weren’t of course. Snowdonia was a couple of hours’ drive in one direction. The Lake District was a similar distance in another. An even shorter drive took us across the fields to Formby where, down on the beach when the weather was right, you could even see them – the Welsh hills a line of shadowy shapes on the horizon, across the wide expanse of Liverpool Bay.

When you’re young, the time between weekends, let alone school holidays, seems endless, and for me those mountains symbolised moments beyond the everyday. Trips to high places were something out of the ordinary, an adventure outside the routine. Not that we always went willingly, of course. For every walk in fine weather, when the view would unfold before us like a piece of elaborate natural theatre, there would be a long trudge to a mist-covered summit where, sheltering from the drizzle behind an oversized cairn or trig point, we’d eat a soggy sandwich and try to imagine what we might be looking at if visibility was greater than about six feet.

But even these moments became worth it after the fact, part of family folklore and stories to be told and retold. And now that I’ve been living away from Britain for more than 20 years, no longer thinking of the island of my childhood as home, the one thing I miss in this city surrounded by the potato and cabbage fields of Brandenburg, is the mountains.

This year has been the first in at least a decade that I have not travelled back to Britain: visiting family and friends, let alone the mountains, has been difficult if not impossible. It’s probably no coincidence, therefore, that this strange and anxious year has been the first in which I’ve really felt the distance between where I am now and where I came from. Thankfully, even when physical journeys are not possible, there are ways to remain connected, and we’ve made the most of them.

Throughout that childhood in Lancashire, and now here in Berlin, I’ve always been able to feel a connection to the mountains, and the Welsh mountains in particular, thanks to the art of Rob Piercy. Rob is a friend of our family, and we grew up with his paintings on our living room wall. We have a print of his here in Berlin too – a view of Snowdonia, that takes us back to Wales every single day.

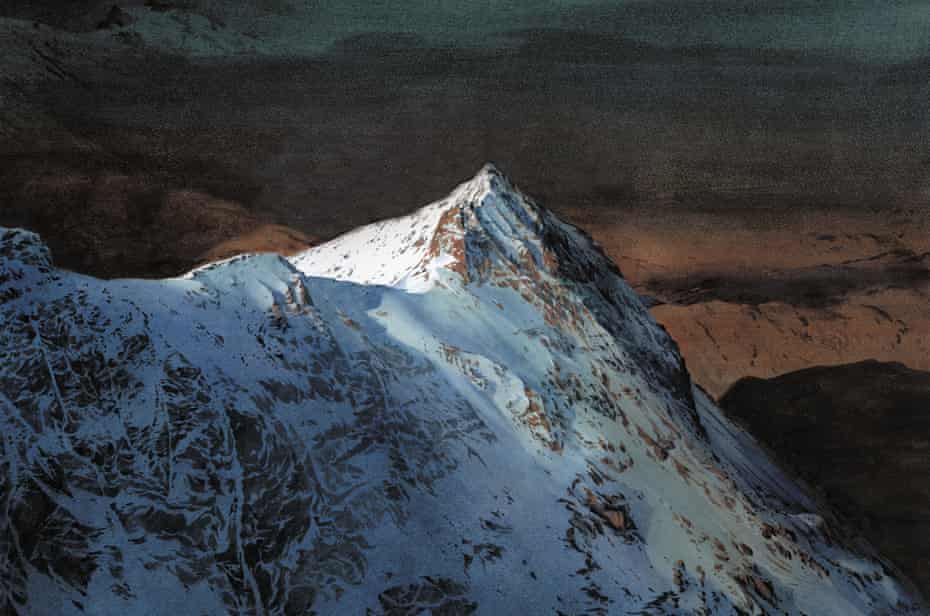

As the landscapes of my youth have been inaccessible, travel to these places and landscapes has remained possible through these pictures, as well as through books and music and films. I spend time with Rob’s paintings. They are remarkable things, as atmospheric and strikingly beautiful as the places themselves, and surely possible thanks only to Rob’s own deep connection to the landscapes. I’m sure if I asked Rob, he could tell me stories relating to each and every one of them. I flick through his book Mynyddoedd Eryri (The Snowdonia Collection), and come to paintings of places – Cwm Idwal and Tryfan, Y Garn and Moel Siabod – that hold in them my own memories, and stories from family and friends.

I was given a signed copy of the book a couple of years ago for my 40th birthday, and I’ve turned to it a lot this year. I read his essays on landscape painting, printed in both Welsh and English, and his walking journal entries, enjoying his reflections on the mountains and his artwork. His passion for these places shines through in his words as it does in his paintings. And he talks about his love for mountaineering, something that I grew up with, and through his words I feel a connection to my parents and those who walked the hills, in sunshine and cloud, with them and later with us.

“Today I have found a magical place,” Rob writes in one of his journal entries, “not far from my doorstep. There are no fine views but here is a place which I feel comfortable in. I can describe what is there to you, but there is more to it than that. As a child I used to feel like this about places and it has a lot to do with large rocks, the smell of heather and gorse … I’m happy to sit here in the warmth of this September day drawing, with one of the rocks as an useful easel and another to lean my back against.”

I’ve often thought that my own writing, in my walks and exploration, is a search for this feeling. As Rob describes, it can often have a lot to do with the places that bring us back to childhood, or other moments from our past when we felt truly happy. I don’t think it is nostalgia as such, for those places remain and can be discovered again. And when a patch of heather on a Baltic island takes me to a Welsh hillside, or the sound of the waves against the rocks returns me to the headland of Rhoscolyn on Anglesey, it adds another story, another layer, and another connection to return to in the future.

Shadows and reflections. The distance remains, but thankfully the rocks and the heather and the gorse are not going anywhere soon, and while we wait for the chance to add stories to places old and new, I can always pick up Rob’s book and let his words and his paintings take me there in the meantime.

This article first appeared on the Caught By The River website. Paul Scraton’s novella In the Pines will be published in 2021 by Influx Press