Through the Greater Caucasus mountain range that forms the northern belt of Georgia, the slim road of the Abano pass cuts a treacherous path. In fact the term “road” is a little generous; for 45 miles, this dirt track cut out of the edge of the mountainside swells and contracts as it snakes upwards to a height of 2,000 metres. The sheer drop along the road edge claims several lives every year, and its reputation was cemented when it featured in the BBC World’s Most Dangerous Road documentary in 2013. But this is the only route to reach the villages of Tusheti, a region tucked deep within these mountains. At the end of the pass, the mountains give way to a grassy plateau as Omalo, Tusheti’s largest village and administrative centre, comes into view.

From June to September, Georgians travel along this road from their homes in Kakheti to escape the lowland heat and spend the season in family homes dotted across Tusheti’s 49 villages. For the rest of the year,the Abano pass is engulfed in snow, with temperatures dropping to -30C, cutting Tusheti off from the rest of the country.

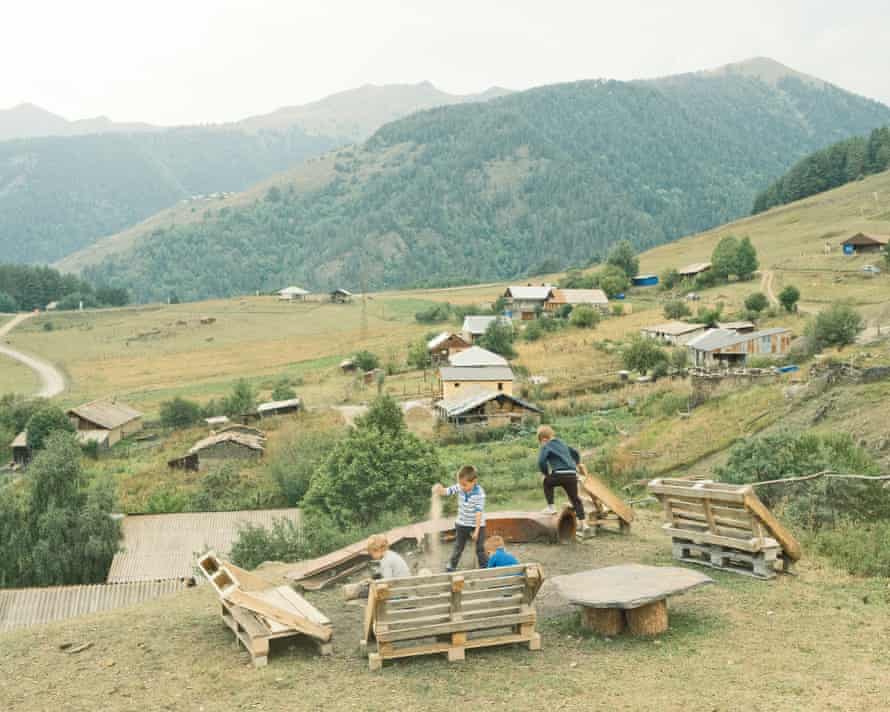

The recent upswing in tourism in Georgia has boosted what is a small and slow-growing economy, and for places like Tusheti, it’s filling a gap left by the shrinking shepherding tradition that’s been the core of Tush culture for centuries. For hikers and adventure seekers, their journey begins with braving the road to enjoy the hiking and wild beauty of Tusheti, and to stay in traditional wooden houses in Omalo or camp in the mountains.

“When I was little, the houses in Omalo weren’t as big as they are now,” says 27-year-old Keti Tauberidze, a medical student from Tbilisi, gesturing to the few wooden homes nearby that share this hillside. Born in Akhmeta, an administrative town in the lowlands close to where the Abano pass begins its ascent, Tauberidze has been coming here every summer since she was a child.

“My grandfather was born here and he built this house,” she says. “I think it’s fun when tourists come here; I like the chance to talk to foreigners, and their presence gives us jobs. Well, not me personally,” she smiles, “but others, sure. Our nature here is wild and unspoiled, and I don’t want that to change.” Their house is simple and sparsely furnished, including a slim, carved wooden bed built by Tauberidze’s great-grandmother.

Above us, the sun dries brightly coloured children’s clothes hanging from a long clothesline strung along the balcony. Keti smiles and apologises: “We’ve had no water for two days, and it suddenly came back on so we’ve had a lot of washing to do!” The three small children playing near us on the balcony belong to her cousin, Nino Kitidze, whose father-in-law was Keti’s grandfather.

“I’m busy with my children now, but I’d like to build my own guesthouse here and run it,” Nino says. Living in Akhmeta for the other months of the year, Nino began working as a babysitter and shop assistant when she was 18 and now sees the tourism boom as an opportunity to do something different.

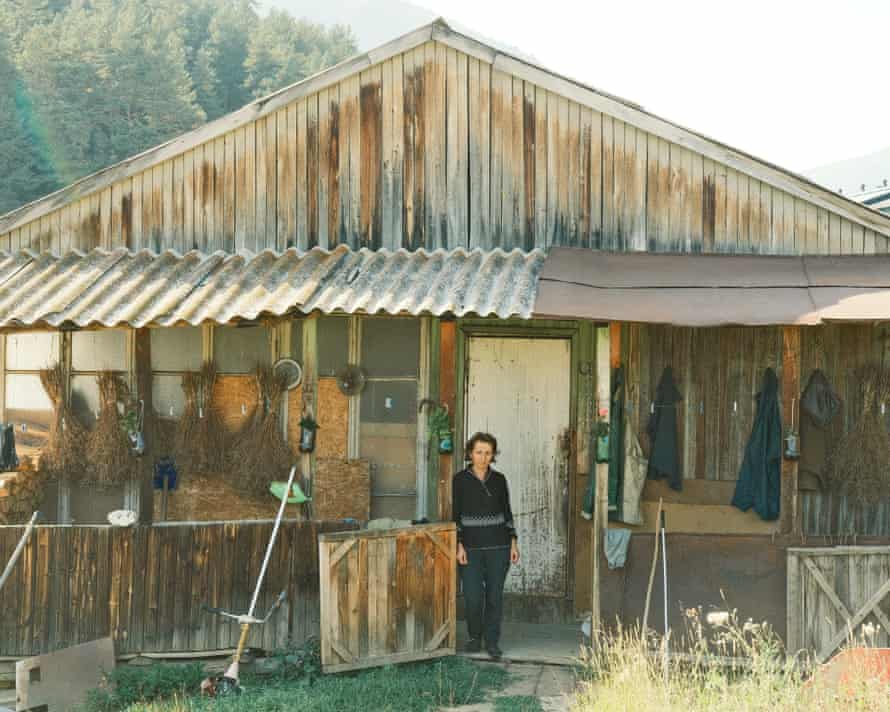

It is easier for young people like Keti and Nino to embrace Tusheti’s changing identity from a shepherding community to a nature attraction for tourists. For older generations of Tushetians, the cultural heritage losses of such change are more palpable. “It’s not that I think tourism is bad,” Nata Abashidze says. Turning 50 this year, she recently changed profession, from dentistry to school teacher after her eyesight deteriorated. She also owns a Akhmeta guesthouse, and says, “I don’t like it when tourists come but don’t offer anything more than the money they pay. If someone comes here, they need to help out, share, live together with us. It’s only money, money, money they think about. I don’t like that.”

The transactional nature of tourism is, it seems, intrinsically at odds with the hospitality for which Georgia is famed. Open-handed hospitality, where a stranger in your home or village would be treated to a welcome and generosity that would last beyond their stay, is a sacrosanct part of Georgian culture. The gains of tourism by way of new jobs and economic growth are thus tinged with the knowledge that part of their cultural heritage will be lost.

“My father was a shepherd here from the village of Tsotava,” Nata says. “When he was 39 he fell off his horse and died, leaving five of us kids behind. My mother raised us by herself.” This wooden house, with a deep porch leading to two rooms, belongs to Nata’s husband and was built by his father.

-

Two men play basketball near the road into Upper Omalo. Maria Gochitashvili, on holiday, rides a horse in Upper Omalo.

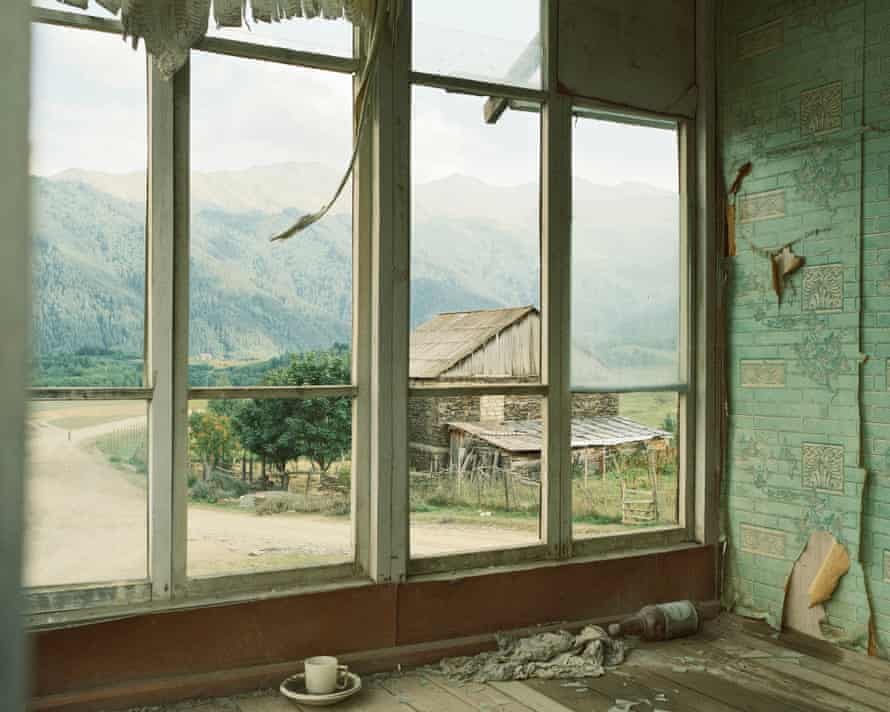

Omalo itself is split into two halves; where Upper Omalo is concentrated into a smaller pocket of buildings beneath centuries-old stone towers that dot the hillside, Lower Omalo is newer, with dozens of houses spread out among the plateau. Many of these are still used, either as summer homes or guesthouses. Others are abandoned or are used as farms for cows and horses for the summer months before the migration to the lowlands ahead of winter.

Migration in Tusheti has been both a product of tradition as well as a source of trauma. Since the 16th century, shepherds have walked their flocks over 120 miles down from the Tusheti mountains to the Kakheti lowlands in autumn, where they live until the spring before reversing their tracks and taking their sheep to the pristine summer pastures in the mountains once more.

But in the 1950s, the Soviets instigated a forced migration of all communities in Tusheti, moving families who had lived there for centuries down to the towns and villages of the lowlands and effectively banning their return. The rupture never fully healed; even after Georgia’s then leader, Eduard Shevardnadze, allowed families to return to their ancestral homeland in the 1980s, few moved back fully. The relative warmth and comfort of the lowlands compared to the harsh conditions of the mountains means that today all but a handful of people leave Tusheti for the winter.

Zura Mouravidze and his wife, Maia, have been coming to Tusheti for decades. Nearly 60, Zura’s relationship with his home in Omalo has evolved from family heritage to one of livelihood. Grazing the Russian republic of Dagestan, Tusheti remains an important border for Georgia to monitor against its Russian neighbour, and a rotating number of Georgian border guards are stationed in Diklo, a village with a vantage over the mountains of Dagestan. Zura is one of them, and throughout the year he comes via helicopter every two weeks to relieve the other guards. “We spend two weeks here, then two weeks in the lowlands to rest,” he says. “It’s not at all easy to be here in winter.”

“For me, Tusheti is Canada, the sea, New York, Washington, even Tel Aviv! Everything is here,” he laughs, excitedly. “But seriously, I love Tusheti so much.” Both Zura’s mother and father were born here. Until 15 years ago, Zura worked in the prosecutor’s office in Telavi and Akhmeta. Ten years ago, the Mouravidzes turned their Omalo home into a guesthouse “for economic stability,” he says. “Tourism is very good for us here. To look back over the last 10 years, life has changed a lot, and for the better. Our infrastructure most of all.”

Without a reason to keep coming back to Omalo and Tusheti, the region once again risks being emptied out of its citizens and heritage. On the drive back to Tbilisi, our car coils down the mountain and we pass so many headstones bearing withered flowers and photos of those whose lives have been claimed by the pass that I stop counting. Almost every conversation with locals about the tourism-centric revival of Tusheti and Omalo returns to a single locus: whether or not the Abano pass will be renovated into a more reliable, less treacherous route to the mountains, and if it is, what they might gain and what Tusheti might lose.