In the wine region of northern San Joaquin Valley, the coarse spindles of pruned grapevines are sprouting delicate creepers that curl toward wire trellises, and cherry trees are shedding soft pink blossoms.

Along with spring, the second harvest season of the pandemic has arrived. Fields and packing sheds soon will be filled with workers, many of whom are migrants and already traveling up the Central Valley as crops ripen.

It is a “pivotal time” to inoculate farmworkers against the coronavirus before they return to their perilous work, said UFW Foundation Executive Director Diana Tellefson Torres.

But it’s also the moment California is tossing out its existing strategy for vaccine distribution — controlled by local governments — and transferring it to a nonprofit insurance company, Blue Shield. The collision of harvest season with the Blue Shield takeover has left many community organizers and health officials worried that existing plans, though criticized for being inadequate and uneven, will be abandoned for a different set of uncertainties.

They say the insurance company has done little to alleviate those fears and has not asked for their help — despite the challenges of working with insular farmworkers, many of whom lack insurance.

“There is no plan we can look at or contribute to,” said Maria Lemus, executive director of nonprofit Visión y Compromiso, a network of promotores, members of vulnerable communities who are trained health liaisons. Her group has been educating farmworkers about the virus for months.

To date, the rollout of vaccines to farmworkers has been hit-or-miss, often driven by local elected officials, unions, nonprofits and employers using their connections to get doses into laborers’ arms. The patchwork system has raised questions about whether vaccines are being equitably shared with farmworkers, but the pending transition seems to be charging ahead without an on-the-ground perspective.

Lemus serves on the state’s Community Vaccine Advisory Committee, aimed at ensuring the distribution of doses has that viewpoint. She has heard nothing yet from Blue Shield on how organizations such as hers will be involved, she said.

“How can we do this together? They should just ask that question. I haven’t heard it yet,” she said. “Invite me to the party. I am happy to help.”

San Joaquin County Director of Health Care Services Greg Diederich echoed that frustration, calling the transition “opaque.” Though Blue Shield was supposed to begin its overseer role with his county last week, it did not, offering little explanation for the delay, he said. In Fresno on Friday, Gov. Gavin Newsom said the transition for “first wave” counties including San Joaquin would happen Monday.

When the transition does take place, Diederich does not know whether his agency will continue to have the ability to run farmworker clinics or “if ultimately [Blue Shield] determines who does what and gets what, and public health kind of takes a back seat,” he said. The uncertainty has prompted county officials in San Joaquin and Ventura to openly ponder whether they can opt out of Blue Shield’s oversight.

Blue Shield referred questions to the state Department of Public Health. A state public health official speaking on background said local health departments will lose most but not all direct control of vaccines, and the list of those allowed to administer the shots will be streamlined to ones the insurance company determines are most capable of reaching equity and speed goals. So far, few details of those changes have been made public.

Equity is a dominant concern in vaccine distribution, and one of the key explanations Newsom has offered for putting Blue Shield in charge. For days, Newsom has toured these politically conservative farmlands — where growers are struggling financially and where the recall effort against the governor is popular — promising protection for laborers crucial to the industry.

Despite earlier concerns, Central Valley Democrats have closed ranks around Newsom as recall organizers push hard in the final weeks of their effort. The Central Valley was hit hard by the virus, with more than 66,000 cases in San Joaquin County alone — though the number of new cases is declining.

But the toll on farmworkers, even young ones, remains starkly disturbing: A recent study found Latino food and agricultural workers ages 18 to 65 in California had nearly a 60% increase in mortality during the last year compared with pre-pandemic times, the highest risk factor for any demographic in the state. White food and agricultural workers saw a 16% increase in mortality, by contrast. The analysis translated to more than 1,000 food and agricultural workers dead from March through October, probably from the virus.

An agriculture worker stacks folded and empty boxes that contained fresh corn at a packing shed in Lodi.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, vice dean for population health and health equity at UC San Francisco School of Medicine and an author of the study, said her concern with centralized distribution is that speed and efficiency will be valued at the expense of those who are harder to reach. She believes it may be better to vaccinate by place — targeting everyone in a high-risk area, especially those in multigenerational and close-knit communities, rather than using tiers of eligibility and mass vaccination centers.

Diederich, the San Joaquin health official, said the county had done an in-depth analysis using data from COVID-19 deaths to assign a risk score to every resident, regardless of state tier, and was moving toward that location-based model. Now, he said, he doesn’t know whether that data will be used.

“It’s fine to do things fast,” said Bibbins-Domingo, “but if you are not actually vaccinating where the virus is, you will not be effective.”

That reality has Jesse Sandoval worried that the coming harvest season will be just as dangerous as the last.

The son of farmworkers who once picked in the fields himself, Sandoval now runs a labor contracting company that employs up to 1,800 people each year, mostly in packing sheds where they often work in lines at conveyor belts that turn crops into the neat packages found in grocery stores.

Recently, frustrated that San Joaquin County officials had not yet started inoculating farmworkers, he called a local politician. That politician, a friend, made a few calls, and within days, Sandoval and a fellow labor contractor had pulled together one of the county’s first clinics specifically for farmworkers, with 750 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

“We just called, I guess, some of the right people,” Sandoval said.

On Feb. 22, as hundreds lined up at a local fairgrounds for their shots, farmworker advocate Luis Magaña showed up to watch. He was bothered by how the appointments had been doled out mostly through employers and labor contractors, and promoted only by word of mouth. Working with other advocates, he waited until the end to snag some unclaimed shots for his own contacts.

“This is like a private event,” he said. “What is the process to apply? I want to organize one.”

Registered nurse Melanie Albor vaccinates a resident at an affordable housing community in Tracy.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The Blue Shield arrangement is meant to address such concerns. On Friday in Fresno, Newsom visited one of 11 new vaccine sites run by another state provider, OptumServe, in the Central Valley, promising mobile and small clinics targeting all farmworkers.

He pointed to 337 community-based organizations that the state and philanthropic partners have funded with $53 million to educate agricultural workers on the virus. Last week, Newsom announced he was moving 34,000 doses — enough to vaccinate 17,000 people — from an unused Walgreens supply meant for long-term care facilities to farmworkers, and increasing the Central Valley allocation of vaccine by nearly 60%.

Newsom said in a statement that the additional supplies were making good on his commitment to “meet our farmworker communities where they are, and deepening the innovate public-private partnerships that exemplify the best of California’s civic spirit.”

He sidestepped a question on Blue Shield’s transparency, citing the difficulties of a transition period and promising “next week that process begins on a whole new scale.”

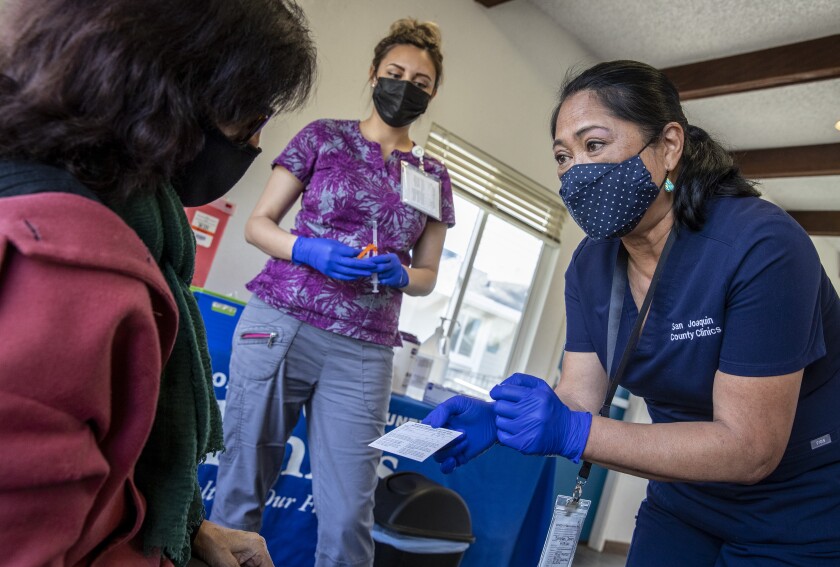

Joan Singson, right, director of population health management for San Joaquin County, and nurse Melanie Albor counsel Parwin Mohammad Assan before she receives a COVID-19 vaccination in Tracy.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

But questions about the transition are growing as quickly as the crops.

Tellefson Torres, from the UFW Foundation, one of the community organizations working with the state, points out that migrating farmworkers may need to get a second dose in a different county than the first. She doesn’t know whether the state has plans to handle that situation.

She also points out Blue Shield’s requirement that vaccine seekers go through the state’s online system is a problem for farmworkers who may lack both internet access and the computer savvy to navigate a tricky sign-up. Until now, her organizers have handled that. It is unclear whether Blue Shield has its own workaround, though it does offer phone sign-ups.

Tellefson Torres said Friday that she asked the governor personally whether federally funded health clinics that serve the uninsured will receive additional doses for farmworkers but received no definitive reply.

“We need to ensure that what is on the books, in writing, is actually happening on the ground and that’s what I’m waiting for,” she said.

In the meantime, she and others are pushing ahead with their own efforts, worried their ability to do so may soon be cut off. UFW Foundation on Sunday was working with Santa Clara’s Monterey Mushrooms to vaccinate 500 farmworkers and planned to do another 500 shots later in the week.

Dozens of other farmworker clinics are popping up across the state, including for strawberry pickers in San Diego and Monterey and date packers in the Coachella Valley. On Feb. 19, a group of 90 Central Valley agricultural employers wrote to Newsom, pledging their locations as vaccine sites if allowed.

Sandoval on Thursday watched as his crew processed a truckload of sweet corn grown in Mexico. Powering up an ungainly contraption that spanned half the length of a hangar-like packing shed, two women grabbed green husks one by one, slotting them on a conveyor belt for a saw to slice off the ends before stripping them down to the kernels. Socially distanced but still close, six masked-and-gloved workers pulled off bits of silk, while others rapidly packed four pieces at a time into thousands of black plastic trays.

When the cleaned cobs reached Gilberto Hernandez near the end of the line, all that was left to do was run them through the wrapper, sealing each package in plastic. It is work this crew has done for years, even as the pandemic swept through last spring.

But this week is different — Hernandez was one of the fortunate who received the vaccine at Sandoval’s clinic.

“I feel good,” he said over the thunder of the machine. “One hundred percent safer.”