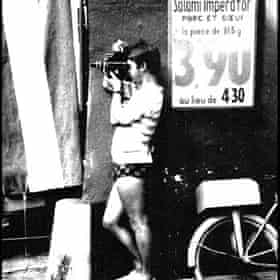

I have a chastening photographic memento of my first trip to Provence, aged 21. I’m slouching against a wall in a back alley in Cannes, dressed in a striped matelot’s shirt, and holding a 16mm Bolex cine camera – the very picture of a nouvelle vague director. It isn’t clear what the camera is pointed at. I’d hired it to film flamingos on the Camargue saltmarshes, but got carried away by the Riviera’s glamorous ambience and took it to the beach, where I promptly dropped it in the sea. It felt like a parable about the insidious impact of tourism in the Mediterranean, a postscript to the process that had led to the naming of Nice’s seafront the Promenade des Anglais.

Several decades later, my partner, Polly, and I fancied trying another kind of Provençal promenade. We were both seriously in thrall to the south of France and wanted to challenge our ageing bodies to 10 days’ sauntering in the remote heart of the region, far from the coastal hustle, among the limestone hills and lavender. We wouldn’t book anywhere to stay in advance, we’d carry everything we needed on our backs, and we’d aim for an inland area that looked encouragingly wild and barely populated.

We set out from Nice at the very end of May, and wiggled our way west by train and bus to the melancholy village of Salernes, which we made our base for the next few days. In its one restaurant that evening, the owner explained that it was a deprived settlement, where most of the men worked in the local quarries.

We walked from there to Villecroze, where there are troglodyte caves. We saw hoopoes and basked in the scent of Spanish broom. But the countryside was changing dramatically. There were building works everywhere: farms being converted, scrubland enclosed behind high walls. When I looked at an aerial photograph later, the most conspicuous feature was a dazzling blue pixellation of new swimming pools. The bourgeoisie were digging in and putting up their high-security gateways.

And it wasn’t easy to get off the roads. The French have mixed views about land access and aren’t particularly interested in rambling. Beyond the Grandes Randonnées system, the concept of a public footpath is a debatable one. We happened to set out at a time when Provence (always politically bolshie) was having one of its periodic wrangles with the EU. We felt we were wandering into a familiar southern thicket, where there is respect for the commune, but not the European community, or anything smacking of meddling officialdom.

France’s Blue series of Topographical Maps sits on the fence in this ancient ideological stand-off, so aren’t much help to a would-be rambler. They paint a perfectly accurate portrait of the countryside – as it might be seen from a satellite. Paths aren’t differentiated from hedges, nor public ways from private.

So we blundered about for days, losing our way repeatedly as waymarks mysteriously ended and paths split, unremarked by the map, into three. It didn’t really matter. The sun shone and nightingales sang. At Sillans-la-Cascade, Polly had a dip in the pool below the waterfall and we heard the fluting of golden orioles. Then we glimpsed one, a female, coloured the same milky green as the limestone river. That afternoon we tramped back to Salernes across country. Stumbling out of a wood after fording a stream, we bumped into the only other walkers we met in 10 days. It turned out we’d strayed into the grounds of a retirement estate called Paradis. They were not much older than us, but called us “courageux”!

We walked south to the tiny village of Montfort-sur-Argens, and fetched up at Le Chat Luthier, a B&B run by Fabrice and Pierre. Their dining room is in a converted cave, fitted with a wall-to-wall aquarium, and there they served us a local supper which climaxed in a dessert of tomato ice and wild thyme sorbet. Fabrice told us of their difficulties in laying out balades (the lovely word for a leisurely stroll) round the village, as part of a green tourism initiative called La Provence Verte. There is no legal status for footpaths in France, and local landowners are suspicious of even informal designation, worried about walkers suing if they fall over on the rocky paths.

The next day we tried following a walk from Fabrice’s map, but it petered out at a chain-link fence. We ignored it and found ourselves in a landscape of poignant, feral beauty, the flipside of the gentrification we’d seen earlier. Farming was retreating from this stretch of Provence, olive-growing losing to cheap fruit from China and North Africa, and the ancient terraces were being invaded by glorious aromatic tides of broom and cistus and rosemary. There were more singing nightingales and orioles, and swooping rollers – like crows but in gaudy shades of blue. These, for better or worse, will be the new cash crops of La Provence Verte.

The walk east to Carcès wasn’t long, but across high ground in searing heat with full packs, was our hardest stretch. We scrumped cherries and peaches from yet more derelict orchards, and had to ask for water at the edge of the village. Carcès was an energising spot to hang out. Multitudes of swifts screamed around our room, bats poured out of the roofs when we explored the town that evening, and we learned the reason so many houses had bottles of water outside: in something close to sympathetic magic, they were meant to deter dogs from peeing against the doors.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind the scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

We cheated at this point and hired a car to drive the 30km to the Massif de Maures, a wild and remote mountain range inland from Saint-Tropez. The north of the forest is Provence’s badlands, an arid savannah of umbrella pines on pink granite bluffs. We explored it along a dried-up riverbed, through drifts of iris and wild tulip, with eagles and turquoise-and-ginger bee-eaters cruising above us. Further south, the forest was denser, a mix of cork oak and chestnut, and the paths were strafed by enormous, two-tailed pasha butterflies. We found managed chestnut orchards among the wild trees, where the trees had grafts from especially productive varieties. Chestnuts and chestnut flour – a common staple this far south – are one of the region’s chief exports.

We spent our last two nights in the cosmopolitan town of Collobrières, in the middle of the Maures forest. It had the feel of a frontier town, with the market’s herb sellers barking in Occitan (which always sounds to me like French spoken by a Brummie) and chic Parisian second-homers and north Africans alike wandering the streets in gorgeous Provençal costume. At the tourist centre, we learned of another row brewing with Brussels, over control of the forest, which, the locals protested, they had looked after successfully for centuries and were extrêmement attached to. We felt they had a point, though the image of those advancing weekenders’ villas wouldn’t go away.

We bought a bag of chestnut flour to take home and wished them well. We had walked through a Provence that is trying, like so many other places, to reconcile many new meanings for the countryside.

The four titles in the Richard Mabey library (The Unofficial Countryside, Beechcombings, Gilbert White and Nature Cure) are published by Little Toller at £18 each, littletoller.co.uk