When the credits rolled on The Silence of the Lambs at the end of its first screening, in October 1990, the audience at the annual ShowEast convention fell silent. No gasps. No uncomfortable chuckles. No applause. Silence. The reaction was unnerving for Ted Tally, the film’s screenwriter, who whispered to director Jonathan Demme, “Do you think it’s possible this movie is too scary?”

“Could be,” Demme said. As the hours and days passed, however, a buzz began to emanate from the people who’d seen it. This pitch-black story about a serial killer had struck a critical chord. The silence, it turned out, was golden.

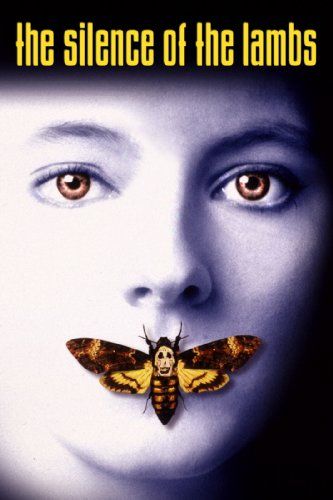

Somewhat perversely, the movie was released on February 14, 1991—Valentine’s Day—and would eventually scare up $273 million at the box office. It was a smash that became the first horror film to win a Best Picture Oscar. Not only is it the greatest—and most bone-chilling—blockbuster of the ’90s, it’s also the rare movie adaptation that’s better than the (very good) book. Jodie Foster gave audiences a new kind of onscreen heroine with Clarice Starling, while Anthony Hopkins delivered the calm menace of Dr. Hannibal Lecter, an all-too-human monster who set the archetype for brilliant serial killers on camera.

But the making of this modern classic was anything but smooth. Like the film itself, it was a nightmare—a string of false starts, fiscal crises, and furious calls for boycotts. As The Silence of the Lambs marks its 30th anniversary, it’s a reminder of a time when studios still fearlessly gambled millions of dollars on dark, provocative projects that weren’t about superheroes, special effects, or theme-park tie-ins.

Thomas Harris introduced the character of Hannibal Lecter in 1981’s Red Dragon. That novel, about a brilliant psychiatrist-turned-cannibal who advises an FBI profiler, was adapted into Michael Mann’s underseen Manhunter in 1986, starring Succession paterfamilias Brian Cox as Lecter. When that film tanked, producer Dino De Laurentiis bailed on turning Harris’s follow-up, 1988’s The Silence of the Lambs, into a sequel. One person who wasn’t put off, though, was Gene Hackman . . . at least not at first. The actor had read Silence and immediately knew it was the property he’d been looking for as his directorial debut. He convinced the cash-strapped Orion Pictures to split the rights with him, and he also planned to play Lecter. Then his daughter read the book. It disgusted her. Hackman dropped out of the project.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

Undaunted, Orion decided to forge ahead. With Hackman out, the studio now needed a new director, fast. Enter Jonathan Demme. At the time, he was an excitingly eclectic filmmaker, equally at home with quirky character studies (Melvin and Howard), concert docs (Stop Making Sense), and screwball comedies (Something Wild). He wasn’t an obvious choice for such disturbing material, but he was thrilled at the prospect of swimming in the murky deep end with the likes of Lecter. “I wanted to make a Psycho-caliber fucking terrifying movie,” Demme said at the time. The director’s first choice for Clarice was Michelle Pfeiffer, the star of his previous film, 1988’s Married to the Mob. But Pfeiffer was squeamish about the film’s unrelenting violence and passed. Fortunately, Jodie Foster had also read Harris’s novel and virtually begged for the role (perhaps, in part, to exorcise her own brush with evil when John Hinckley Jr. shot Ronald Reagan in 1981 to impress her). “The thing I love about Clarice Starling is that this may be one of the first times I’ve ever seen a female hero that’s not a female-steroid version of Arnold Schwarzenegger,” Foster said. “Clarice is very competent, and she is very human.”

As for Lecter, the studio wanted Sean Connery. But like Pfeiffer, he was repulsed by the subject matter. At the time, Anthony Hopkins was universally regarded as one of the most gifted (and intense) actors of his generation, but he was hardly a bankable name. Orion decided to roll the dice anyway. “I read the script and, boom, I knew intuitively how to play him,” Hopkins said. He called his Lecter a combination of Katharine Hepburn, Truman Capote, and HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. On the set, Foster and Hopkins never spoke to each other when cameras weren’t rolling, all the better to fuel their characters’ creepy onscreen duet.

When the time came to release the film in late 1990, there was a problem: Orion was a mess, teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. The studio couldn’t afford to market both Silence and its other Christmas 1990 release, Dances with Wolves. So it put Lec-ter on ice and dumped the movie into theaters the following February. It was an instant commercial and critical success.

Not everyone was a fan, though. LGBTQ activists picketed the film over its negative depiction of a trans character—Ted Levine’s Buffalo Bill. Demme would strenuously defend the characterization, but there’s no denying that the issue remains a stain on Silence’s legacy.

The outrage didn’t trickle down to the Academy, which rewarded it with seven nominations. The film that had begun with Gene Hackman and slipped through the fingers of Michelle Pfeiffer and Sean Connery would go on to become only the third movie in history to sweep the “big five” categories at the Oscars—Screenplay, Actor, Actress, Director, and Picture—joining 1934’s It Happened One Night and 1975’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Today, The Silence of the Lambs remains as brilliant and bloodcurdling as it was three decades ago. It sparked three further movies (2001’s Hannibal, 2002’s Red Dragon, and 2007’s Hannibal Rising), an acclaimed NBC series (also called Hannibal), a new CBS series debuting this month (Clarice), and countless “It puts the lotion in the basket” memes. Why? Because Hannibal Lecter is the bogeyman we love to hate and hate ourselves for loving. Even with a scant 16 minutes of screen time, his meat hooks got into our psyches and refused to let go. Decades before we would develop an obsession with lurid true-crime tales, here was a film that seemed to be infinitely more terrifying than anything that existed in the world beyond the multiplex. It showed us that evil could be hypnotically seductive, thrillingly deviant, and deliciously unnerving—especially when paired with fava beans and a nice Chianti.

Get 87 Years of Award-Winning Journalism, Every Day

Join Esquire Select

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io