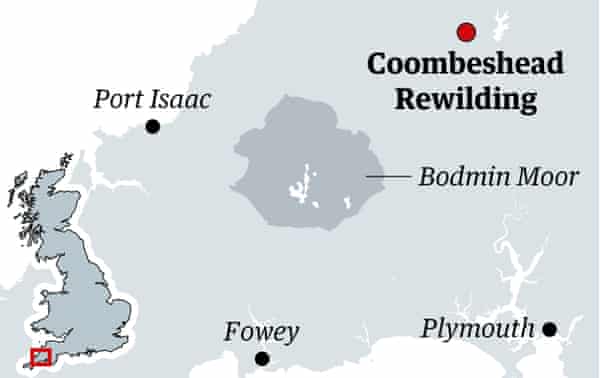

The field sloping away to the west at first appears straightforwardly idyllic. There is a pair of pretty shepherd’s huts with adjoining kitchens in a meadow where dandelions and cuckoo flowers bloom. And there is a glorious view over pasture and woodland towards the blue hills of Bodmin Moor.

But this is the British countryside accompanied by a large dollop of strangeness, particularly at dusk.

“Quick!” calls an unearthly being from the alders behind our hut. “Crhrup!” replies another.

I follow the sound through the trees to an aviary. Inside is a black stork the size of a child and a posse of night herons, exotic cream-and-inky-midnight-blue nocturnal birds. Their “Quick! Crhrup!” calls echo through the silent valley. Neither species is a wild resident of Britain, although that may change if Derek Gow gets his way.

We’re staying at Coombeshead in north-west Devon, a 61-hectare (150-acre) farm being rewilded by Gow. Every landowner seems to be dabbling with eagles and beavers these days, but Gow is the rewilders’ rewilder. A blunt, visionary Scot known as Mr Beaver (his book Bringing Back the Beaver was published last year), Gow supplies water voles, beavers and storks to restoration projects around the country.

Now, after years of enabling others’ rewilding, Gow is restoring “natural processes” to his once-conventional sheep farm. What does this mean? Part of the answer comes when I step from our hut to use the composting toilet at night and jump at the sound of a colossal groan from the blackness. A hulking presence with two curved horns looms against the sky – a water buffalo.

The following morning, as the mist slips from the distant moors, we have breakfast at the picnic table outside and more beasts appear, separated from the huts by an unobtrusive barbed-wire fence. The buffaloes’ curved noses give them a quizzical, intelligent look; there’s also a cluster of skittish dark Exmoor ponies. The most approachable animals are the “iron-age pigs”, a wild boar/Tamworth cross whose spectacular rootles make the pasture look like it has been ineptly ploughed.

Gow’s farm seems a quirky menagerie, but each animal has a purpose and the operation is driven by his genuine passion for restoring Britain’s denuded natural landscape. These herbivores roam freely in the former sheep farm and its woodland because Gow is seeking to replicate the actions of extinct grazers – wild horses, cattle and boar, whose browsing and rooting (and dung) was historically a great driver of biodiversity.

The beneficial effects of (not too many) free-living herbivores has been shown at Knepp, the rewilded farm in West Sussex that has inspired British rewilding. The pigs break up the grassy sward so wildflowers can take root; buffalo wallows hold water and are home to insects and amphibians; and the absence of chemicals means dung beetles and other invertebrates flourish.

Gow hopes tourism will fund his restoration. Guests can stay in five new huts, all spaced for privacy across two fields, plus a spruced-up old Gypsy caravan. Each hut sleeps two, and a hot shower and composting toilet are shared by three huts. There’s also a camping field with four pitches. In an open-sided barn is a communal area with pizza ovens, a charging point for phones and cameras, wood-fired barbecues, sofas and board games. The tranquillity is ensured by a no-under-10s and no-dogs policy.

We find the sensitivities of the animals around us encourage stillness. Each evening, we walk quietly to a raised platform overlooking six large enclosures filled with trunks and stumps of old trees. Inside, two eyes glare back at us from tall grass: a wildcat, one of six pairs that will lead a captive-breeding effort to reintroduce these tabby and tawny-patterned predators into England and Wales 200 years after they were driven to extinction. From the platform, we have views of Gow’s “sky table”, on which he places roadkill deer carcasses in the hope of luring passing white-tailed eagles. (One visited earlier this spring, but not during our stay.)

On our second day, we take a two-and-a-half hour “animal encounter” tour, which is free for glampers and can also be booked by day visitors. We begin by bumping through the fields in Gow’s old Land Rover to admire what he says proudly are Britain’s only herd of Heck cattle. “Nobody else wants them. They’ve got a terrible reputation,” he beams. Truly wild cattle were hunted to extinction in Europe in medieval times, but these aggressive versions, bred in Germany in the 1920s, are here to perform the same role – roughing up woodland and grassland, creating opportunities for other species to move in.

We’re then taken to Gow’s captive-breeding centre, which is like peeking behind the curtain of a small zoo, except each animal’s offspring will be restored to the wild. Photography tours are available for day trippers as well as campers, and Gow also offers bespoke tours for visitors particularly interested in reintroducing species, such as harvest mice or beavers.

The yard rings with a hollow clattering – white storks gently clashing beaks in bonding behaviour. We enjoy closeups of harvest mice, beavers, cranes and, perhaps most impressive, Gow’s “vole room”. There were once millions of Kenneth Grahame’s “Ratty” in Britain; today, the wild population is 77,000 and falling fast. This summer alone, Gow will release 1,700 water voles to aid conservation efforts. One species that won’t be liberated are three stunning lynx, which he rescued from a private collection. Accustomed to controversy over reintroductions, he acknowledges it may be some years before lynx are successfully returned to Britain.

Water voles and everything from fish to dragonflies thrive in beaver-created wetlands, and this explains Gow’s obsession with this chunky, herbivorous rodent.

Close encounters are wonderful, but it’s a deeper pleasure to discover beavers in the wild. On our final evening, Gow leads us into the heart of his valley, where beavers live freely. We admire the scale of their stick-and-mud dams which, incredibly, rise two metres in places. We wait quietly beside a pond. While beavers slumber in capacious stick “lodges”, we enjoy a kind of dusk bathing, watching long-tailed tits flit through the woods as a willow warbler makes its somnolent descending call.

No beavers show themselves but watching for them is a magical experience on a unique farm that will only get wilder and more bewitching as the years roll by.

Shepherd’s huts at Coombeshead Rewilding from £100 a night (two-night minimum) including wildlife tour. Beaver watching is £25pp; photography/wildlife walks/rewilding workshops available for day visitors as well as glampers; one-day wildlife photography course £140pp for groups of three, £55pp for groups of 8-12. Camping from £22pp a night

Five more rewilding projects to visit

Cambrian Wildwood, near Aberystwyth

In the uplands of mid-Wales, close to the River Dyfi and the sea, the Cambrian Wildwood project aims to restore habitats and species (including pine marten, red squirrel and, eventually, wild boar and beaver) and give people the opportunity to experience nature. Focusing initially on 300 hectares (750 acres) of degraded valley and moorland, it plans to extend the wildwood to 3,000 hectares, through buying land and working with neighbouring landowners. It is first and foremost a community resource, and programmes bringing children and young adults to the wild are core to the project; but there are hiking trails and wild camping zones for all to enjoy.

Trees for Life, Highlands

The charity Trees for Life runs a 4,000-hectare rewilding estate at Dundreggan, west of Loch Ness. The mission is to restore the landscape to what it once might have been, which involves large-scale tree-planting after years of destruction, and the reintroduction of wildlife, including wild boar and pine marten. Visitors can join paid-for conservation weeks (be warned – they book up far in advance), and a visitor centre and accommodation are set to open here in 2022.

Somerleyton, Suffolk

More than 400 hectares of farmland on the Somerleyton estate, on the Norfolk-Suffolk border, is being largely left to rewild itself, with cattle, wild ponies and deer roaming free and playing a role in the natural regeneration of the land. There are plans to reintroduce bison, too. While the estate can be visited for the day, staying onsite at Fritton Lake in luxury cabins, cottages or rooms offers a more immersive experience. There’s a lake for boating and wild swimming, and activities include foraging and estate tours. Owner Hugh Somerleyton is one of the founders of Wild East, an initiative to encourage people in East Anglia to return 20% of their land to the wild (whether that’s a small garden or a huge farm).

Wild Ken Hill, Norfolk

Hosting the Springwatch team this year, Wild Ken Hill is an exciting initiative to rewild 400 hectares and manage an 800-hectare regenerative agriculture project and a 200-hectare freshwater marsh. It has just launched 14 guided tours, from a family-friendly excursion (think digging for earthworms and “micro” beasts) to dawn-chorus safaris and more in-depth rewilding tours. A campsite is planned for next year.

Knepp, West Sussex

One of the longest-established and best-known rewilding sites in the UK, Knepp is famous for its work in helping boost populations of turtle doves, nightingales, purple emperor butterflies and tree-nesting peregrines, and for a pioneering white-stork breeding programme. The 1,400-hectare farm, close to Horsham, is open to day visitors, and also offers camping and glamping. There are regular “safaris” and workshops focusing on subjects from ancient trees to the ecology of rewilding.

For more information on rewilding projects in the UK see the Rewilding Network (rewildingbritain.org.uk)

Jane Dunford