I wonder if the founders of Factory Records always knew their work would be exhibited in a museum one day, so decided to curate it all from the off.

From its inception, Factory used a cataloguing system that gave a FAC number not only to every record released, but to its artwork, films, related miscellany and even the odd living being, including the office cat, Feline Groovy (FAC 191).

Neatly enough, items FAC 1 to FAC 50 form the basis of a new exhibition, opening on Saturday at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum, called Use Hearing Protection: the Early Years of Factory Records. It explores the history of the label’s formative period, from 1978 to ’82 – the years before New Order’s gamechanging Blue Monday (FAC 73) and the brouhaha of the Haçienda (FAC 51) and Madchester.

Factory was a work of a conceptual art as much as a record label for Joy Division and New Order (and later the Happy Mondays), so an exhibition is the perfect way to tell the story of how it rose from gloomy, post-industrial Manchester to showcase the most important band of the post-punk era. The music was sumptuously packaged by graphic designer Peter Saville: his beautifully clean and timeless record sleeves and posters are the highlight of the exhibition for me. They could have been produced in prewar Bauhaus Berlin – or just last week.

Immaculately preserved artefacts have been called in from the families of co-founders Tony Wilson and Rob Gretton. Another section focuses on the label’s female voices, including the blueprint for Linder Sterling’s Factory Egg-Timer (FAC 8), a menstrual abacus.

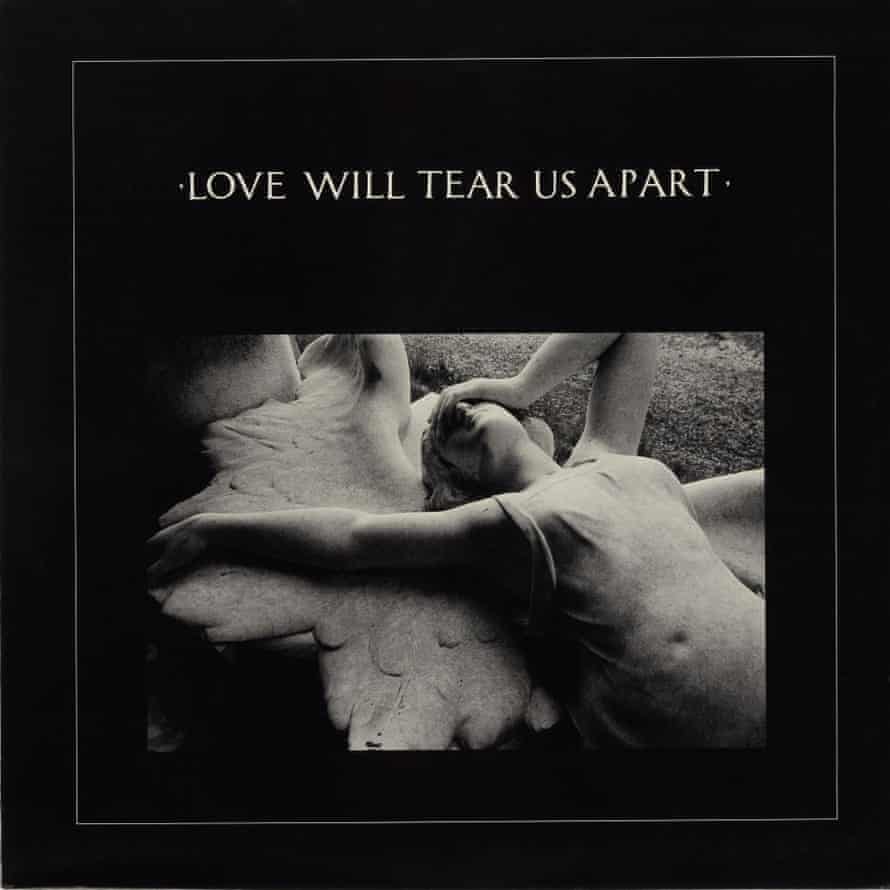

There’s the small synthesiser Joy Division’s Bernard Sumner built from a DIY kit, soldered together under the desk where he worked as an animator when no one was looking, and the huge red Perspex G from the nameplate of Granada Studios, where Wilson worked. The star exhibit is Ian Curtis’s Vox Phantom VI teardrop guitar, which he played in the video for Joy Division’s Love Will Tear us Apart, and which recently sold at auction for £162,000 (it’s back here on loan).

The interactive display the museum had planned had to be shelved because of Covid restrictions, but the exhibition ends with two fun installations: the Gig Room, where large screens show footage of early Factory bands playing on TV shows; and a mini Haçienda designed by Ben Kelly, designer of the exhibition space as well as the original club – a nod towards the next step in The Factory story. Visitors are welcome to dance in both spaces.

Sadly, seeing gigs and dancing in the city’s clubs is still off the agenda, but being a music anorak I jumped at the chance of exploring the locations related to the exhibition with Manchester Music Tours.

The tours were started by Inspiral Carpets drummer Craig Gill in 2005 in response to being constantly asked about the history of the local music scene by customers at his record stall. His widow Rose has run the company since Craig’s death in 2016 – leading bus tours for fans of the Smiths, Oasis, the Stone Roses and Joy Division/New Order – but have been on hold since the first lockdown. However, with tours due to restart next month, I was lucky enough to get a taster. (Three/four-hour tours £30pp, private tours can also be arranged).

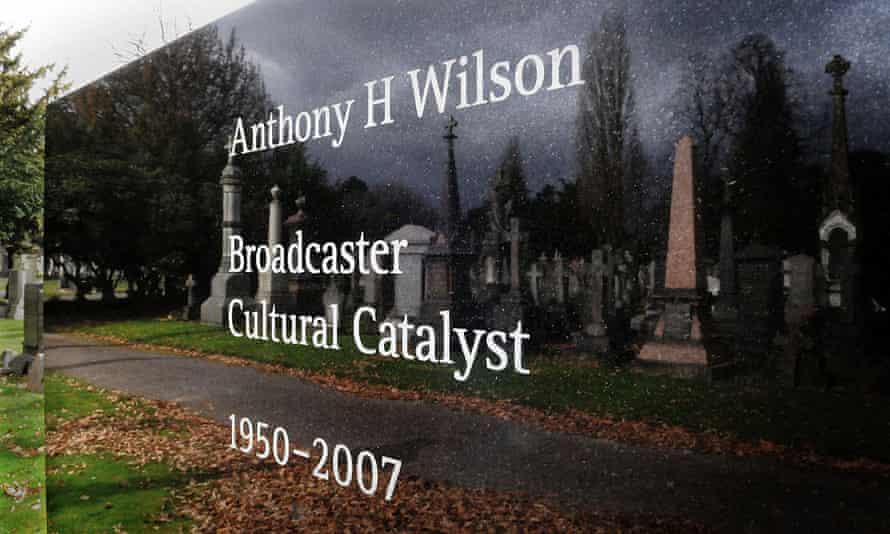

We continued the Factory theme by visiting the label’s first offices in West Didsbury; the Epping Walk Bridge in Hulme, where Kevin Cummins took the iconic shot of Joy Division standing moodily in the snow; the Haçienda apartment block that stands on the site of the nightclub; and in the vast Southern Cemetery in Chorlton-Cum-Hardy, Tony Wilson’s grave. Although his headstone doesn’t have a catalogue number (that practice ended with his coffin, FAC 501), the Factory aesthetic is instantly recognisable in the beautiful minimalist design by his friends Saville and Kelly. The black marble is so polished it reflects the cemetery like a mirror and is engraved with the words “cultural catalyst” – an epigram the grandiose Wilson would have loved.

Rose then drove me round the Didsbury streets where she hung out with Inspiral Carpets and the then-unknown Oasis in the early 1990s, pointing out the pub they’d all gather at on a Sunday after larging it all weekend. She wistfully recalled how Liam, “who was going out with my mate at the time, would walk home from the pub down this street on a Sunday, with no shoes on”.

Rose is as passionate about the people behind the stories she tells as she is the music. Our tour was running late but she suddenly did a U-turn as she couldn’t miss checking in on Mr Sifter, owner of the fabulous old secondhand record shop mentioned in Shakermaker by Oasis (“Mr Sifter sold me songs when I was just 16”). “I just need to check he’s been OK in lockdown … God, I hope the shop is still open!” It is, but it’s been a struggle. She often pops in on Noel and Liam’s mum, Peggy, too.

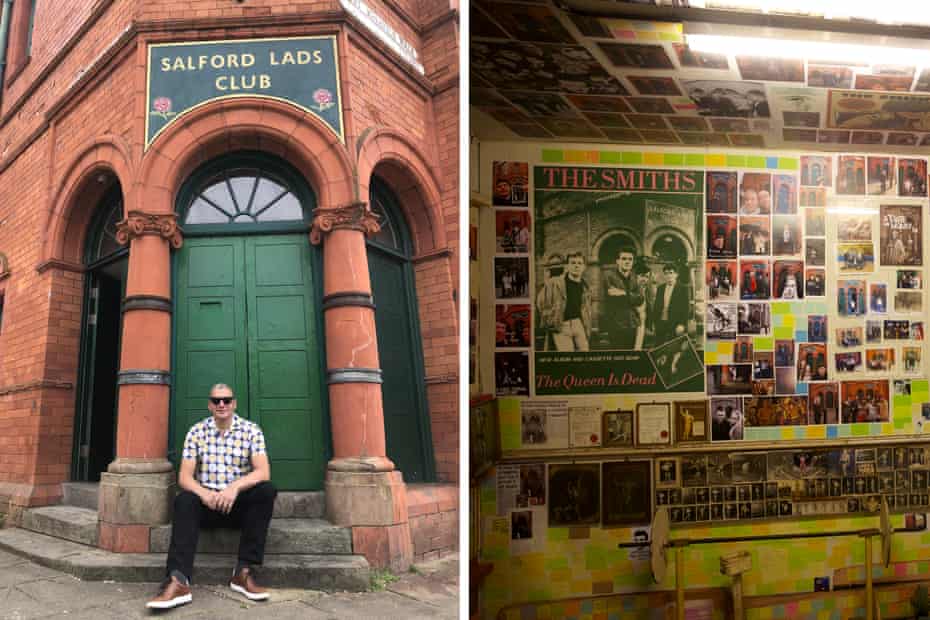

The highlight of the tour was Salford Lads Club, featured in the famous photo on the 1986 Smiths album The Queen Is Dead. I didn’t know that the redbrick club was on the corner of the actual Coronation Street – or that that street even existed – but it’s probably why Morrissey, a Corrie connoisseur, chose the club for the photoshoot.

The biggest surprise, though, is the fascinating history behind its green doors. The club opened in 1903 and its Edwardian interior has hardly changed – the walls are covered in old photos and sporting prizes, and the original wooden floors have endured over a century of local boys (and girls since 1994) boxing, weightlifting and playing football and are still in place. As project manager Leslie Holmes showed us around the Tardis of a building, I could smell the history in its concert halls, billiards rooms and gyms – all sadly empty since the pandemic. The kids will be back in next week hopefully, and a visitors’ open day is scheduled for 25 July.

Given the global interest generated by the Smiths photograph, in 2004 Leslie had the brilliant idea of opening a Smiths Room, which has become a shrine, plastered with thousands of photos of fans from across the world posing like the band in front of the club. “This project has taken over my life in a way,” said Leslie. “I can’t think of many countries other than North Korea that I haven’t received a photo from.”

Where to stay

The shell of the Italian palazzo-style Free Trade Hall, once Manchester’s leading gig venue and the scene of (at least) two concerts that have become part of rock’n’roll folklore, now fronts the Edwardian hotel.

In June 1976 the Sex Pistols played the Lesser Free Trade Hall. There were only about 40 people in the audience, but legend has it that nearly all went on to form a hugely influential band or be involved in the music industry, including Morrissey, the Buzzcocks, Joy Division, Mark E Smith of the Fall, music writer Paul Morley and, of course, Tony Wilson.

A decade earlier, shortly after “deserting” his folk roots, Bob Dylan took to the Free Trade Hall stage with an electric guitar. It was all too much for one folkie in the audience, who famously screamed out “Judas!” at his idol. In response, Dylan told his band to play the next song “fucking loud!”

The concert halls have long gone but this remains the hotel of choice for many visiting musicians. The rooms (doubles from £129 room-only) are gorgeous, some with views over Manchester’s hotchpotch city centre.

The building has another, more significant historical connection. It was built on St Peter’s Field, the site of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, when 18 people were killed in a cavalry charge as they gathered to demand electoral reform. The event led directly to the formation of this newspaper almost exactly 200 years ago, but that’s another brilliant story.